Iíve come across some

weird couplings in my time but this

oneís the beeís pyjamas of weird couplings.

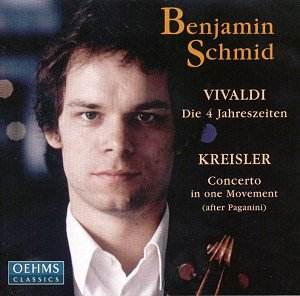

The rising Austrian star fiddle player

Benjamin Schmid has yoked together a

warhorse so leathery that itís barely

fit to saddle with a Kreislerian concoction

that should properly be classified under

Paganini and is, in any case, never

played. This is the arrangement, adaptation,

extrapolation (what have you) of the

first movement of the Italianís D major

Concerto, the First, though the quaint

words "after Paganini" do

serve well enough. Letís start there.

In his publicity material

it seems that Vienna hailed their returning

son as a Kreisler redivivus when

he performed there with the Philharmonic.

Which is odd. Tonally and stylistically

we know Schmid admires Ivry Gitlis,

a maverick wild card if ever there was

one, and listening to Schmidís playing

of the one movement concerto one feels

the greater pull of the contemporary

than any residual expressive features

that Kreisler may have bequeathed. That

doesnít mean of course that one demands

Schmid apes Old School devices but does

serve to show his determination to meet

a work of this kind on his own terms.

There have been very few recordings

of this work but Kreislerís own, with

the Philadelphia and Ormandy, is clearly

hors de combat and the early

post war Decca that Alfredo Campoli

made with the National Symphony Orchestra

and Victor Olof in London was profoundly

of the Kreislerian ethos Ė itís available

on Dutton but I donít like the transfer.

So maybe itís high time that a steelier,

more firmly centred and square jawed

performance was put on disc in good

sound. Certainly the orchestra commits

some forward sounding solos Ė room for

harp and a fine clarinet Ė but the focus

is on Schmid who executes his harmonics

and the tough cadenza with notable aplomb.

Of overt affection thereís perhaps less

on show.

In the Four Seasons

Schmid at least surrounds himself with

a small band, the Camerata Salzburg,

composed of fifteen strings and a harpsichord/organ

continuo. Some little orchestral swellings

in the Allegro of Autumn attest to a

concern for some influence from original

instrument performances. But in the

main these are modest, crisp chamber

orchestra sized traversals of the concerti.

There are some rather too emphatic moments

in the same concertoís slow movement

Ė and some strong ornamentation as well

Ė but Schmid digs into the opening of

Summer well and without indulgence.

His finale here is bold with roughened

articulation. He cultivates an expressive

depth in the slow movement of Autumn

and the off beat pizzicati are perky

in its finale. Winterís ice is well

conveyed in its opening Allegro Ė good

and brittle Ė though the Largo sounds

restless under the ice thaws of the

pizzicati accompaniment. Interestingly

he employs some subtle rubati here,

though for my taste the tempo is all

too historically informed - fast. His

ornaments are by no means excessive

and reasonably well thought through.

The sound varies from

performance to performance; the Vivaldi

is intimate and attractive, the Kreisler-Paganini

just a touch blowsy though not really

problematically so. The notes are in

German and English and recommendation

is well nigh impossible inasmuch as

this is a unique coupling. In the end

choice will be artist based, especially

since the Kreisler only lasts seventeen

minutes.

Jonathan Woolf