Respighi’s Marie Victoire

edited by Ian Lace

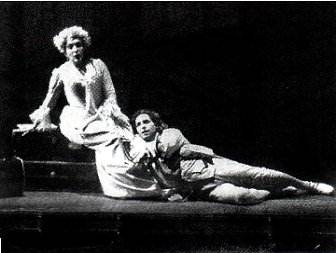

Nelly

Miricioiu and Alberto Gazale in a duet

scene from the premiere of Respighi’s

Marie Victoire (uncredited photo

issued in the Italian music magazine

Opera, January 2004 issue)

The world premiere

of Ottorino Respighi’s opera Marie

Victoire (sometimes referred to

as Maria Vittoria in Respighi’s

later Italian version. The original

is sung in French) was staged at the

Teatro dell’Opera in Rome in late January

and early February 2004. It starred

Nelly Miricioiu as Marie Victoire de

Lanjallay and Alberto Gazale as Maurice

de Lanjallay with Alberto Cupido as

Clorivière.

Respighi had written

Marie Victoire at the beginning

of the second decade of the 20th

century and yet it has lain unperformed

until this year. It clearly possessed

considerable merit for the directors

of La Scala Milan and of the Costanzi

Theatre (now the Opera House) in Rome

were impressed and Maestro Tullio Serafin

examined it; but pressures to stage

other operas of Verdi and Wagner precluded

its production in1913. And then the

Great War intruded with consequent cuts

in expenditure for new works. And so

Respighi’s opera lay in the publisher’s

drawer for many years and no doubt Respighi

was pressed for other work.

The opera is based

on the drama, Marie Victoire,

by the French author Edmond Guiraud

first performed at the Théâtre

Antoine in Paris in April 1913. Guiraud

is also credited with the libretto for

Respighi’s opera. Marie Victoire

holds a place at the centre of Respighi’s

output (No. 100 in the Catalogue

of Music by Ottorino Respighi)

Marie Victoire

is a work of the composer’s early maturity

and it comes between two other Respighi

operas: Semirâma and Belfagor.

On this occasion, the instrumental aspect

of the music is more transparent than

for Semirâma, the orchestra

being of normal size and rather bare

of percussion. The correspondent of

Il Resto del Carlino, making

the above comparison, wrote of Marie

Victoire as being freer, lighter,

less pompous or heroic; more sentimental,

more intimate, more theatrical ... the

singing is natural, the melody preponderant"

On might imagine that

Marie Victoire would be

an obvious progression from its predecessor

Semirama in which Respighi had

already found his own voice. Listening

to the off-air recording of the first

performance for the first time, one

might not immediately recognise the

usual Respighi ‘footprints’. Indeed,

in the first act, one might be forgiven

for mistaking the music for Richard

Strauss. But as the opera progresses

the accustomed voice of Respighi becomes

more apparent. Interestingly, there

are pre-echoes of melodies which would

be present in subsequent works.

One of the Respighi

Society members, after listening to

the work said, "As I listened repeatedly,

I appreciated the work more and more,

recognising it as a valuable addition

to Respighi’s opera canon. The orchestration,

elegant and somewhat lighter than that

of Semirama’s is well up to his

finest standard. He repeatedly used

the fascinating device of inserting

pastoral ballads of the story’s period,

juxtaposing them against the dramatic

emphasis of his music. From time to

time the subject and its treatment brought

to mind Poulenc’s Dialogues des

Carmélites, particularly

when a Carmelite novice is to be executed.

But Poulenc could never have heard it

or seen the score of Marie Victoire."

"The orchestra

in the Rome premiere performance was

more than adequate and conveyed the

constant swings of mood excellently

as did the principals. I do not enjoy

excessive vibrato in the human voice

and sadly that took away some pleasure

in this performance. At the end one

recognises it is a good story, of great

drama, well told and composed with fine

skill."

The Plot The

opera tells the story of the effect

of fear and the blood-letting of the

first year of the French Republic on

a respectable and honourable countess;

the pressures changing the behaviour,

character and response of those about

her. Her gardener becomes her gaoler

and finally she sees him as her only

family. It lasts for 2½ hours and is

sung, as composed, in French.

Act 1 In her

chateau ((the noble mansion of Lanjallay

at Louveciennes) Countess Marie sings

a pastoral ballad at the harpsichord,

only to be warned by her gardener, Cloteau

that it is dangerous to sing a song

written for the widow of an enemy of

the Republic. A quarrel between Cloteau

and Kermarec another servant ensues,

the music rising. Finally her husband,

Maurice, urges her to continue, only

to be interrupted by the drums and shouts

of an approaching mob. Trying to continue,

her voice is countervailed by the mob’s

singing of the Carmagnole, and

their demanding the death of all aristocrats.

Their leader flourishes decrees authorising

this and conveys that he must hear of

any suspect activity. After Maurice

and Simon, a Deputy of the Gironde,

assures them that nobody present can

be suspected, the mob leaves, singing.

A charming love duet between Marie and

Maurice is followed by the entrance

of Clorivière bringing news that

Maurice’s father is in danger in Brittany.

They deplore the condition of the nation

and an attendant slips away to contact

the mob leader. Departing for Brittany

with Kermarec, Maurice makes a fond

farewell, exchanging declarations of

everlasting love and Chevalier Clorivère

reprises the ballad at the harpsichord.

The lovely melody of the parting takes

on a darker colour as Marie sings, conveying

a sense of approaching doom. A violin

obbligato echoes the melody sadly, the

harp enhancing it. Marie weeps inconsolably,

when to her horror the alerted leader

returns with members of the mob and

they seize Clorivière. There

follows the music of a brief dance of

menace, reminiscent of Belkis. Finally,

the curtain falls to a gentle rendition

of the ballad by the violins, then augmented

by the woodwind.

Act 2 - is set

in a convent chapel, in use as a prison

for enemies of the Republic. Marie sits

with a poet, Simon, and a sad old man,

with his granddaughter, a Carmelite

novice, while the Marquis de Langlade

tries to interest fellow prisoners in

enacting a Rousseau play. The curtain

rises to a roll of drums, that is displaced

by a wordless song (la, la), which becomes

a minuet to be danced in the play. Marie

protests at the levity, demanding respect

for the feelings of those approaching

death. The following dispute is quelled

by the entry of Cloteau, who is now

her gaoler. He promises violins for

the Rousseau performance. Then, from

the courtyard, comes the singing of

the choir for the play, juxtaposed with

sad expressions of fear by the grandfather

and novice. Suddenly Cloteau announces

that Maurice too is held by the Committee

of Public Safety. Simon despairs that

his fate will be no better than theirs;

the only hope would be Robespierre’s

death. The choir continues rehearsing

and Maria sings to a violin accompaniment.

Recalling their childhood together,

Clorivière declares his love

for Maria, to her consternation. Clorivière

is furious when overheard, but he continues,

causing an argument with Simon, which

is interrupted by a roll of drums, whereupon

the commissioner arrives. Cloteau reads

the names of those to be executed: two

Marquises, a Chevalier, Clorivière,

Marie, Simon, the Abbé and the

novice. A dance and song by the prisoners,

precedes the grandfather’s plea to be

taken in place of the novice. The drums

fade to create a serene end to the scene.

Cloteau laments that

Marie has been denounced and that he

is now serving her tormentors. She forgives

him and she departs supported by Clorivière.

A planted spy begins to mock them and

Cloteau challenges him and in the argument

he and Simon kill him, the timpani underlining

the drama.

Marie returns, her

face reflecting shame and the outrage*

she has suffered. She sings with deep

sorrow, seeming to have no life left

in her; she recognises that she is damned

forever. The Marquis continues to mount

the play, the violins striking up the

overture and the drama commences. Then

a bell chimes eleven, drums and shots

are heard and an entr’acte contains

music for the play, interposed with

the crowd singing the Carmagnole and

with music expressive of impending death

and her dishonour.

This quietens to music

heralding a calm dawn, the oboe prominent.

A shot, tumult and drums shatter this,

Cloteau shouting that Robespierre is

dead. Recognising they are saved, the

prisoners rush out, leaving Marie. Crying,

she sings that the guillotine would

have cleansed her soul and that now

she must endure a dishonoured life.

Act 3 It is

Christmas, six years later in the Paris

boutique where Marie sells hats. Milliners

tease Cloteau in a lively passage, establishing

a mood far from the previous act. Emerantine

enters with Marie’s five-year old son,

Georges, and she quarrels with Cloteau

until Marie tells him to close up. The

mood has changed and she sings sorrowfully

to Maurice in heaven, protesting her

innocence and that she lives only to

serve the needs of Georges. The music

calms and Simon joins her announcing

that Clorivière is coming before

quitting France. She embraces her son

and there is a knock on the door. The

strings again establish calm, before

Clorivière’s entry and Marie

tells Georges to embrace the crying

gentleman. On his knees before Georges,

Clorivière begs him to pray for

him, then leaves unforgiven, the music

redolent of his grief; he had hoped

for some hint of comfort. Alone with

Cloteau, Marie tells him always to set

another place at table, as he is now

her only family. They reminisce, the

mood calm, without a hint of turmoil,

when an owl’s hoot alarms them and the

music mounts in anticipation of further

drama.

Maurice and his manservant

arrive; they had gone to America assuming

that Maria had perished. The strings

lead through to a romantic reunion between

man and wife. An explosion startles

them and Georges cries out. Maurice

asks if this is their son and Marie,

mad with suffering, admits it is not

his heir. There is the sound of frantic

galloping and cries of death intervene

as Clorivière enters admitting

he has tried to assassinate Bonaparte.

Seeing an extra place at the table,

Maurice assumes that Clorivière

is the father. The music mounts as they

confront one another, Maurice forcing

him to leave, whereupon the police,

soldiers and others pour in accusing

Maurice. Seeing no future for himself,

he accepts the blame, as the crowd cries

for blood, leaving Marie alone in the

sacked boutique, the strings taking

the drama to a high point as she calls

out her husband’s name. The music subsides,

but a rhythmic pulse emerges, leading

to a slow instrumental prelude, the

music presaging the drama of the final

scene.

The last scene is set

in the courtroom of Maurice’s trial.

When he will not respond to her, Marie

makes an impassioned admission of guilt

in allowing herself to be violated,

explaining the torment she has suffered.

A drum beat punctuates her public humiliation.

Tears spring to the eyes of Maurice

and the judge, and the public call for

Maurice to forgive her, which he does.

They demand his exoneration, but Maurice

refuses to indict the man who has besmirched

his honour. Cloteau intervenes to name

"the filthy beast" but Clorivière

stands and proclaims his own guilt,

while asking Marie and Maurice to forgive

him. They do and Clorivière shouts

his defiance of the regime, grabs a

pistol and sings the ballad which opened

the opera. The song and cries for his

blood are cut short. He has shot himself.

* As in so many

operas, much is left to the imagination.

Here it is left to the listener to fill

in what has happened off-stage. It must

be supposed that in the witnessing of

so many bloody executions, Marie, anticipating

that she, herself, would shortly fall

under the guillotine, had sought comfort

and passion with Clorivière