MAURICE JACOBSON

(b. London, January

1, 1896;

d. Brighton, February

2, 1976)

by Michael and Julian

Jacobson

see

also Part 2: The Music of Maurice Jacobson

Maurice Jacobson was

regarded in his lifetime as a "musician

extraordinary", gifted with such

exceptional versatility that formal

classifications were quite inadequate

to convey the wide-ranging nature of

his career. Among his manifold activities,

he was a composer, pianist, conductor,

music publisher, editor, broadcaster,

lecturer, and doyen of British music

festival adjudicators. Use of the word

"versatility" sometimes implies

a certain sense of dilettantism; in

Maurice Jacobson’s case, however, he

proved himself a master of every musical

field to which he devoted his boundless

enthusiasm.

Jacobson, who was awarded

the OBE in 1971 for "services to

music", began his professional

career as a solo pianist early in life

- he was, in fact, a child prodigy,

having started serious lessons in both

the violin and the piano at the age

of seven. At 16, he won a piano scholarship

at the Modern School of Music, London,

which enabled him to receive lessons

from Busoni. By that time, he could

play all Beethoven’s sonatas and all

of Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues from

memory, a feat which many eminent professional

musicians would envy. In 1916, he gained

an open scholarship at the Royal College

of Music, where, with a four-year break

for military service in World War I,

he studied composition under Stanford

and Holst and conducting under Sir Adrian

Boult, until 1922.

Outside Buckingham Palace (with his

wife, Suzannah), after receiving his

OBE

It was typical of him

that, even in the Army, he formed a

brass band among his fellow-soldiers

- himself playing any of the brass instruments

that lacked a performer.

He matured so quickly

as a musician that, while still a student,

he served as accompanist for two years

to the great tenor John Coates. This

ended only when Coates wanted him to

go to the USA for a recital tour. By

then, Jacobson had just married and

had also begun his lifelong association

with the music publishers J. Curwen

& Sons. (The replacement Coates

chose to tour with him was a 24-year-old

named Gerald Moore, later to become

Britain’s most famed accompanist ...)

Although his main career had moved in

other directions, Jacobson remained

much sought after by leading soloists,

whenever he could find the time.

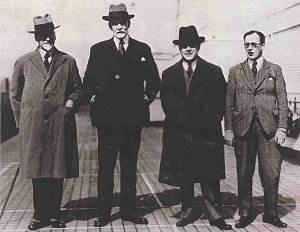

A truly historic shot. It was taken

aboard the liner "Majestic" in 1931,

when Maurice made his first Canadian

festival tour with a team of "All-Time

Greats" in the adjudicating field (of

whom he was destined to become recognised

as one of the greatest).

From left to right, the team members

are: Sir Hugh Roberton (founder and

conductor of the world-famed Glasgow

"Orpheus".Choir; Harry Plunket Greene,

the great Irish baritone; Harold Samuel,

the pianist and Bach specialist; and

(bearing a striking resemblance to Buster

Keaton), one Maurice Jacobson, then

aged 35

From the start, even

so, there was never any doubt that his

greatest love in the musical field was

composition. One early success came

when he won the Sir Louis Sterling composition

prize, organised by the Jewish Chronicle,

which enabled him to buy the first top-quality

grand piano of his own.

It was a perennial

regret that, because of the growth of

his other activities, he didn’t compose

as much as he wished or felt he should

have done. Nevertheless, a list of his

known works, first prepared for his

centenary in 1996, showed eventually

that his compositions and arrangements,

including collections, reached the respectable

total of some 450. In his last radio

interview, recorded on his 80th birthday

on January 1, 1976, he said that he

still hoped to compose - intimating

that, although a majority of his output

had been vocal works, he thought that

his next composition would probably

be instrumental. This despite the fact

that, because of his failing eyesight,

his doctor had registered him officially

a month earlier as "partially blind"

(A full musical

appraisal of his principal works will

be given in a later article.)

Although from a Jewish

family, Jacobson never regarded himself

as a Jewish composer, per se.

Even so, the influence was occasionally

apparent. In 1932, he took on a part-time

post as Choirmaster at the West London

synagogue in Upper Berkeley Street -

generally accepted as the headquarters

of Reform Judaism in Britain and long

famed for the extra-high quality of

its organ music, in particular. To quote

its obituary notice after his death:

"Very soon his enormous enthusiasm

had brought about a lively choral group

and a splendid choir." Music he

wrote for the choir in this period is

still used regularly in the synagogue

services, notably his harmonising and

arrangement of an ancient Hebrew melody

to the words of Psalm 92. By 1937, he

found that he was away from London too

frequently to continue as Choirmaster,

but he served as chairman of the synagogue’s

music committee from then until the

Second World War and again from 1958

to 1964. He remained a member of the

committee to the end of his life.

It was also during

the mid-1930s that Jacobson was commissioned

by the Markova-Dolin company to compose

the music for a new biblical ballet,

David. With Anton Dolin dancing

the title rôle, it was premiered

in 1936 and subsequently had more than

120 performances. One song from the

ballet music, Psalm 23 set to

Tonus Peregrinus, was later published

separately with the words in both English

and phonetic Hebrew versions.

Another of biblical

origin, regarded as among the most successful

of his individual works for solo voice,

was The Song of Songs (from the

‘Book of Solomon’). The two published

versions, for low or medium voice, with

piano, were derived from the theme threading

through Jacobson’s music, integral to

the scripts, for the six "Men of

God" radio plays broadcast by the

BBC in 1946-47. (Each of the plays was

devoted to a Hebrew Prophet: Elijah,

Amos, Isaiah, Hosea, Jeremiah, and John

the Baptist.)

The BBC Sound Archive

has a broadcast of The Song of Songs

by Kathleen Ferrier on November 3, 1947,

with Frederick Stone at the piano. For

a later broadcast, by Helen Watts, the

composer himself was the accompanist.

He last heard it at an 80th birthday

concert given for him in Brighton, a

month before his death. It was sung

by a young Tees-side contralto, Ann

Lampard, who had immensely impressed

him when he judged her in the Vocal

Solo classes at Ryton Music Festival

in 1973. The words were also read at

the Service of Thanksgiving for Jacobson’s

life, given in London at the "musicians’

church", St Cecilia’s, in March

1976.

Adjudication

To the general public, he was best known

as an adjudicator, having judged at

most of the nearly 300 music festivals

in the UK, as well as making numerous

return visits to festivals in Canada,

Hong Kong and elsewhere. He first rose

to international prominence as the youngest

member of the vintage team which judged

festivals across Canada in 1931, its

other members being Sir Hugh Roberton

of Glasgow Orpheus Choir fame, the great

Irish baritone Harry Plunket Greene,

and Harold Samuel, the pianist and Bach

specialist.

The flavour of these

festivals was caught in an Evening

Standard article by Stephen Williams,

later a well-known BBC music producer,

who interviewed Jacobson in July 1938

after he returned from three months’

adjudicating in Canada with Roberton

and Steuart Wilson. In all, the team

had judged 64,000 competitors. Williams

quoted Jacobson as saying:

"Music there is

considered of paramount importance by

the educational authorities. The bright

schools, in fact, are the music schools.

In a class for junior orchestras at

Vancouver, there were two entries -

one from Kamloops, 250 miles away, the

other from Nelson, 523 miles away.

"The Kamloops

players brought a full symphony orchestra

(except bassoons) of 80 instruments.

The journey cost 700 dollars, which

had been subscribed by their fellow-townsmen.

The Nelson orchestra, strings only,

had given six concerts in the previous

year to raise the 500 dollars for its

transport. These players were between

13 and 17 years of age. I have heard

many worse performances by adult professional

orchestras."

The article added that,

at Montreal, Jacobson judged competitors

of 17 different nationalities. Most

of them were French, and he had to deliver

all his adjudications in French and

English. He instanced as proof of the

freemasonry of music the fact that,

at one festival, Roman Catholic choirs

conducted by priests competed with choirs

of many different denominations in a

Protestant church.

Jacobson’s last visit

to Canada was in 1967, for the country’s

centennial celebrations and again he

gave many of his adjudications in both

languages at many of the festivals.

(He had always loved France, and his

study library included a full shelf

of French literature.)

One immediate outcome

of his early Canadian tours was to cement

what became a lifelong friendship with

the Roberton family, as well as a very

close musical association, particularly

over the publishing of Sir Hugh’s prolific

compositions and arrangements of Scottish

folk-songs, which have since become

part of the regular choral repertoire.

A letter to him from Roberton in March,

1950, concluded:

"What you have

done for Curwen’s, what you have done

for me, for us, for ours; your patience,

your pertinacity, your unchanging loyalty

and affection - all these remain with

us ‘as a perfume doth remain in the

folds where it hath lain’. Of this there

is no possible doubt. So here’s to the

days ahead! May you be given time and

chance to bring to a complete flowering

all that lies deep within you."

Elsewhere overseas,

Jacobson’s successive visits to Hong

Kong from 1959 to 1972 saw the event

more than quadruple in size, to become

the world’s largest music festival,

with some 70,000 competitors. For his

first visit, he was the sole adjudicator.

When his younger son Julian, following

in his footsteps, last judged at the

festival in 2004, he was one of a

sizeable panel of adjudicators

now needed to cope with its continued

growth - there were 24,000 candidates

for the piano classes alone ...

Altogether, Jacobson

worked in the festival field for more

than fifty years, often describing himself

as a "musical missionary".

Appraising his work, Lionel Salter once

wrote: "The first quality about

MJ which springs to mind is his phenomenal

memory - a memory which could be incredibly

specific. On the Thursday or Friday

of a busy festival week, he could turn

and say, ‘Don’t you think that this

girl has the same teacher as that one

we heard on Tuesday?’ This memory, developed

to a remarkable extent, compensated

in many ways for his poor eyesight."

In like vein, Larry

Westland recalled: "I sat by him

at a festival on Teesside, where he

listened to twelve performances of Du

bist die Ruh by Schubert. He made

no notes, and yet adjudicated each intimately,

from memory."

Jacobson’s failing

eyesight put an end to what he himself

described as one of his "parlour

tricks" - his gift, on the festival

platform, of being nearly always able

to pick out individual contestants about

whom he was talking and point to them

in the audience (usually much to each

individual’s gratification, as can be

imagined). Given the often hundreds

a day competing before him, it was no

mean feat. Loss of this trick apart,

however, it was impossible to keep an

old warhorse down. By 1974, when he

was chairman of the judging panel at

"Music for Youth" in the Fairfield

Halls, Croydon, someone was taking his

elbow to help him safely down the sloping

aisles towards the platform, to give

his adjudications. Yet the moment the

platform hove into view, he shook off

the helping hand, bounced up the steps,

and was straight into action. Irrepressible!

Several of the contestants

Jacobson first judged as amateurs at

local festivals were later destined

to become household names. In addition

to Kathleen Ferrier, whom he first encouraged

to become a professional singer after

judging her at the Carlisle music festival

in 1937, when she was 25, his other

"discoveries" included such

leading British artists as Norma Proctor,

Denis Matthews and Dame Ruth Railton,

founder of the National Youth Orchestra.

Jacobson himself was at one time a joint

musical director of the NYO and chairman

of its executive committee for its first

17 years. He was also a guiding light

behind the National Festival of Music

for Youth (which gave rise later to

the Schools Prom, now a three-day annual

event at the Royal Albert Hall).

A lesser-known aspect

of his finds is that sometimes they

were indirect, in the form of advice

to fellow-adjudicators or others, rather

than taken under his own wing. Agnes

Duncan, MBE, a stalwart of the Glasgow

festival (which, incidentally, was the

last at which Jacobson ever adjudicated,

in October 1975), was 97 when she recalled

this incident from long before:

"At the adjudicator’s

table with him once, we had just listened

to a young girl of 17 or 18. She sang

Verborgenheit by Wolf. MJ leaned

over to me and said, ‘Agnes, do you

know this girl?’ I said that I did.

‘Well, keep an eye on her - she is going

to reach the top. See that she goes

to a good teacher’." His advice

was heeded. The girl’s name: Marie McLaughlin!"

[The script of a Radio

3 broadcast on the work of an adjudicator,

given by Jacobson on February 9, 1973,

is at the end of the section on Radio

Talks.]

Kathleen Ferrier

Jacobson was the chief

adjudicator at the Carlisle music festival

in 1937 when Kathleen, then 25,

twice came before him - initially as

a pianist, in the Open Piano Class,

which she won. Then, to his surprise,

she reappeared later as a singer. She

had won the contralto class (judged

by another), which entitled her to go

forward for the festival's supreme Rose

Bowl prize. This time MJ was the adjudicator

again and had no hesitation in placing

her first. When the curtain came down

afterwards (at Carlisle's old Playhouse

Theatre), he had a word with her. She

explained that she had entered the singing

class "just for a lark".... In fact,

it turned out, she had actually done

it for a bet. Some friends had dared

her, and she'd gone in for it just to

win a wager of sixpence! That’s one

story; another is that the bet was from

her then husband and was for one shilling.

Either way, Jacobson recounted that

he said to her: "I don't know anything

about your private life, but your voice

has got a beauty which is quite unique

and, if you contemplated a professional

career, I'm sure there's a place of

any size waiting for you."

It was this initial

encouragement which led her to start

taking serious singing lessons, initially

with a well-known teacher at Newcastle

and then with Roy Henderson.

When she came down

to London after the outbreak of World

War II, it was Jacobson who first taught

her German, for singing purposes, and

accompanied her at her first London

performance. Subsequently, they gave

a great many recitals together to audiences

in factory canteens, air-raid shelters,

bombed churches, even to people sheltering

from the Blitz under railway arches.

This was under the aegis of CEMA (the

Council for the Encouragement of Music

and the Arts), forerunner of the

Arts Council. One of the last times

he played for her was at the Dover Music

Club, where shells from German guns

on the French coast were screaming overhead

as she sang.

Some while later, however,

when he conducted a performance of his

cantata The Lady of Shalott with

the Etruscan Choral Society at Hanley

on May 11, 1944, she sang in the first

half of the same concert. (Among her

songs were Che faro from Gluck’s

Orfeo and Stanford’s The Fairy

Lough.) The tenor soloist for the

cantata was Peter Pears. It was the

first time he and Kathleen had met,

and there can be no doubt that this

led to her first meeting with Benjamin

Britten and her operatic debut in his

The Rape of Lucretia in 1946.

She remained a family friend to the

end of her all-too-short days. (She

died of cancer on October 8, 1953, aged

only 41.)

Curwen’s

Jacobson’s work with

Curwen’s, then one of Britain’s leading

music publishers, began in 1923 as a

part-time reader and editor; he was

appointed a director in 1933 and was

the firm’s chairman from 1950 to 1972,

having played a key part in ensuring

its healthy survival throughout WW2.

His help and musical advice were long

recognised publicly by many people who

were already prominent composers (such

as Ralph Vaughan Williams) or were later

to become so.

In his last radio interview,

he recalled that he met VW while still

at the RCM, studying composition first

with Stanford and then with Gustav Holst.

At one period, Holst fell off a platform

and hurt his head badly, so his classes

were taken over by other composers,

including VW. Since these temporary

teachers often contradicted each other,

the students would have fun by interjecting:

"But Gustav said this ..."

To which VW or some fellow stand-in

would reply: "Yes, but I say

this!"

Despite their age difference

- Vaughan Williams was 24 years older

- they developed a lifelong friendship

and deep mutual respect. Jacobson described

him in these terms: "Absolutely

stable, to a degree. Serene, strong,

and full of fun. He seemed never to

change. Witty and affectionate. His

influence was in his own modesty and

humility."

As an illustration

of these latter qualities, VW would

sometimes call in at Curwen’s when he

was stuck over some problem of scoring.

"He just came along and said: ‘I’m

not very happy about this, Maurice.

What can I do about this?’" And

Jacobson’s suggestions were accepted

without demur.

In fact, their collaboration

dated as far back as 1923, the year

after Jacobson left the Royal College

and started his part-time work at Curwen’s.

The words of VW’s Mass in G minor, published

that year, were in Latin. The firm had

been asked to do a version in English

and, at VW’s suggestion, the task was

confided to Jacobson. The difference

in the number of syllables, between

Latin and English, made it anything

but a simple job - and the young editor

would call on VW every two weeks, to

seek approval for what he had done to

date. A first outcome was that the English

version was eventually published as

being "By Maurice Jacobson, in

collaboration with the composer."

A second outcome occurred

nearly thirty years later, after the

copyright of this version was renewed

in 1951 and it was then among the music

chosen for the Queen’s Coronation service.

The full music for the service was published

by Novello in 1953, with the Creed credited

jointly to R.Vaughan Willams and Maurice

Jacobson. At one stage during the preceding

months, VW visited Curwen’s to discuss

the details and, in passing, asked MJ

what he had received for the work. Nothing,

Jacobson said. He’d regarded it as part

of his job for the firm. It speaks volumes

for VW’s simplicity and generosity that,

there and then, he made Curwen’s check

all his royalties for the English version

of the Mass since 1923 and insisted

that MJ should get half.

Jacobson’s genius as

a music editor was recognised instantly

by virtually everyone who had dealings

with him in that field. Gordon Reynolds,

organist and choirmaster of the Chapel

Royal, Hampton Court Palace, paid this

tribute to him: "I met him after

submitting some song arrangements. It

would have been reasonable to send them

back with the comment ‘These need improving’.

Instead, I was privileged to receive

a lesson in polishing which I have never

forgotten, and that one session was

the happiest and most memorable piece

of teaching I have ever experienced.

Moreover, I was being paid for it! Maurice

Jacobson must have made countless friends

through such acts of kindness."

The Man

Parallel with the fact

that he did indeed have innumerable

friends, from many walks of life, this

last compliment begs the question: Yes,

but what kind of man was he in private

life?

Two features which

would immediately come to mind, for

those who knew him best, were his love

of abstruse word games (habitually played

over meals with family or colleagues)

and also of perpetrating the most ghastly

puns. He was also an avid collector

of variegated "funnies", as

witness this letter in his collection,

dated July 2, 1959:

"Dear Sir, Please

send me down two series of ‘The Treasury

Sight Reader’ by Maurice Jacobson,

and inform me how I must pay, if it

is on delivery or otherwise. By sending

me these music, you would be helping

me keep out of the RUM SHOP - so please

help. Beasley Sirju, Princes

Town High Street, Trinidad, B.W.I.

He also exulted in

a press notice from The Gloucester

Journal, dated September 10, 1910,

which started with enthusiastic coverage

of a Three Choirs performance in the

cathedral of Elgar’s The Dream of

Gerontius, and then related the

prior first performance of a work for

string orchestra by VW, conducted by

the composer. The notice observed, inter

alia: "The impression left in the

mind by the whole composition was one

of unsatisfaction (if we may use such

a word). We had short phrases repeated

with tiresome reiteration, and at no

time did (it) rise beyond the level

of an uninteresting exercise. The band

played the piece as well as it could

be played, and we had some nice contrasts

in light and shade. But there was a

feeling of relief when (it) came to

an end, and we could get on to something

with more colour and warmth. The piece

took nineteen minutes in performance."

And the "(it)"

in this case? VW’s Fantasia on a

Theme by Thomas Tallis!!

Jacobson’s lack of

personal pomposity was abundantly evident

in an incident in March 1963 when, conducting

a choir of 400 children at Lincoln festival,

his trousers sank to his knees and,

while clutching desperately with one

hand, he carried on conducting with

the other but then had to struggle to

the rostrum rail and sit on it, albeit

still conducting the now near-hysterical

children. The cause was not all that

funny, in fact. On the way to King’s

Cross station for his train to Lincoln,

a car cut across the front of his taxi,

forcing the driver to brake sharply;

MJ banged his nose, and the blood flowed

on to his suit and best shirt. Hence

the trouble with the temporary replacements.

MJ not only took it

in very good part - "I’m in good

company, it once happened to Sir Thomas

Beecham" - but was also exasperatedly

amused to show a sheaf of press cuttings

about the incident from all over the

world, even in Japanese. In addition,

ever afterwards, his study displayed

the original of a Daily Mail cartoon

referring to it, by Emmwood.

But perhaps the most

illuminating insight into his character

was afforded through Dr David Clover,

a prominent figure in the field of musical

education in the Sheffield area and

a noted extrovert, known for his jocularity

and bonhomie. Clover, still remembered

affectionately though dead these many

years, was by the adjudicator’s table

when a particularly attractive girl

arrived on the platform to compete.

Ever anxious to share the good things

in life, he drew Jacobson’s attention

to her. MJ had the gift of being able

to listen intently to each entrant while

continuing to write his notes. He paused

and lifted his head. "Very choice",

he commented succinctly - then bent

his head and resumed writing.

There are many points

that could be deduced from those two

pithy words - not least that, although

Maurice had as much an eye for a pretty

girl as the next man and wasn’t going

to rebuff the extrovert by failing to

show appreciation, he would not waste

time on it during festival hours.

Radio Talks

BBC talks about music

formed another prolific aspect of his

"musical missionary" rôle.

The topics ranged from record reviews

to the part played by tone colour in

modern music, from an appreciation of

Ivor Gurney’s songs to a large number

of concert interval

talks (on works by Bach, Beethoven,

Dvořák, Elgar, Vaughan Williams,

Walton and others), from the difference

between classical and romantic music

to a series on English Brass Bands and,

the ultimate accolade, an appearance

on January 29, 1969, as the castaway

in Roy Plomley’s weekly Desert Island

Discs. The eight records he chose

were:

- Bach Magnificat - Munich

Bach Choir and Orchestra

- Ravel Daphnis and Chloë

Suite No. 2 - Philharmonia/Giulini

- Shakespeare/Morley, It was

a Lover and his Lass - John

Coates, Gerald Moore (piano)

- Stravinsky The Rite of Spring

- Paris Conservatoire Orchestra/Monteux

- Holst Neptune, from The

Planets Suite - Members of

London Philharmonic Choir with Philharmonic

Promenade Orchestra/Boult

- On December 25th

- Orpington Junior Singers

- Beethoven Symphony No. 3 in E

flat major, op. 55 - Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra/Beecham

- Stanford The Fairy Lough

- Kathleen Ferrier, Frederick

Stone (piano)

For his luxury, he

requested caviar; and for the extra

books, some paperback detective stories.

Unsurprisingly, he had cogent reasons

for each of his musical choices. But

a whole spread of reminiscences was

encapsulated in his explanation for

having selected The Fairy Lough

as his last choice:

"... just to hear

(again) the sheer beauty of Kathleen’s

voice; to remind me of Stanford, my

first composition teacher. It was one

of his songs, and one of the greatest

songs ever; to remind me of John Coates,

because I must have rehearsed it and

played it for him hundreds of times."

Jacobson was also responsible

for inaugurating the highly popular

BBC programme "Let the People Sing".

His last major radio talk, however,

interspersed with records of his choice,

was on the activity to which he had

devoted fifty years of his life, the

work of an adjudicator. Re-titled impiously

within his immediate family circle as

"The Adjudicator Squeaks",

it was broadcast on Radio 3 on February

9, 1973. Here is the script:

"Sir, you have

insulted my wife!" (The wife on

this occasion was a thick-voice, unmusical

contralto to whom I had just given invaluable

advice.)

[Larry Westland

recalls that the incident occurred at

a North of England music festival and

that the outraged husband tapped MJ

on the shoulder with his umbrella before

protesting.]

"Don’t cry, Jonathan.

I’m sure the adjudicator didn’t mean

to be unkind. I don’t suppose he could

play your little piece any better than

you did." Or, at a more advanced

level, a competitor who played sparkling

Scarlatti as if it were richly romantic

Rachmaninoff, who was heard to remark,

"Oh, I won’t win; that adjudicator

doesn’t like my style."

To say nothing of an

adjudicator - not myself (though it

might have been) - after an unpopular

decision in a big choral class, being

bundled to the back exit of the hall

and smuggled under rugs in a taxi to

the station.

... And I could give

you many more true stories to show that

an adjudicator’s life is by no means

all sweetness and light, and is subject

often enough to unpredictable hazards.

These are not always voiced as in the

examples with which I started this talk.

Even more difficult to come to terms

with are the dissenting unspoken thoughts,

the surly silences instead of the approving

applause, the hostile glares displacing

the grateful smiles.

Now, at the other end

of the scale, listen to this well-beloved

voice - Kathleen Ferrier singing Roger

Quilter’s To Daisies, the song

with which she won the famous Rose Bowl

at the 1937 Carlisle Music Festival.

A few days before this

Rose Bowl victory, I had awarded Kathleen

top place in the open piano competition

at the same festival. She had in fact

played many times in piano competitions

at various festivals, always learning

something from the experiences, and,

I don’t doubt, from her adjudicators.

After Carlisle she continued to compete,

advancing first steadily, and then rapidly

forward along the road that was to lead

her to international fame.

But - and this is the

point - she had entered and competed

for sheer love, with an avid appetite

to learn, in which mistrust of the adjudicator

held no part. And so it is, with very

few exceptions, with the vast number

of competitors at music festivals who

present themselves for public performance

and adjudication year after year.

These festivals are

unique in the world’s music-making.

They provide a performing platform for

all ages from the tenderest upwards

- a testing ground for teachers, pupils,

choirs, conductors - with an interested

audience making up its own mind, and

ready to agree or disagree with the

adjudicator.

What does the adjudicator

do? According to his capacity and the

terms of his engagement, he listens

to class after class of contestants

showing their paces before adjudicator

and audience - singers, choirs, pianists,

string players, woodwind and brass soloists,

guitar, accordion, ensembles of every

sort from a couple of players upwards,

school orchestras, bands, full orchestras

... verse speaking, too. I’d like to

say more about the adjudicator’s duties

in a moment. But it must already be

clear that he is not an examiner, just

as a competitive festival is not an

examination.

Festivals are open

to anybody who will come and play, sing

or hear; whereas Examinations are held

behind closed doors with only the candidate

and the examiners present.

The examiner assesses

- privately; the adjudicator teaches

- publicly. The keen teacher will make

judicious use of both forms of challenge

to him- or herself and pupils.

Now I want you to hear

some children, aged 8 to 11, the Seafield

Preparatory School from Lancashire,

frequent competitors at festivals. Their

gifted trainer attributes the beauty

of their singing largely to advice garnered

from adjudicators. They will sing the

Irish folksong The Sally Gardens,

arranged by Benjamin Britten.

Did you notice that

I used the word "advice",

not "criticism"? I often wish

that the word "criticism"

could be expunged from the music festival

vocabulary. True, a disappointed parent

may say on occasion, "He criticized

my Jennifer severely". Well, if

he did, Jennifer must have deserved

it! But, in fact, most adjudicators

bend over backwards to avoid giving

offence. It is pointless to administer

pills too bitter to be swallowed. Even

more harmful can be apologies to competitor

and audience for bad work, or giving

undeserved praise.

We don’t look for an

exalted standard from every competitor.

We estimate the present standard of

each performance, and - as do all teachers

- give as much advice as the individual

can assimilate and employ at that stage.

The higher the standard, the more searching

the counsel, whether for interpretation

or technique. The better the work, the

more the adjudicator is looked to for

constructive advice.

And so it is that,

over the seventy-odd years of festival

activities in Britain and the Dominions,

the standard of both the performance

and the quality of music has steadily

advanced. There are ups and downs, of

course. But the main advance is clear.

An adjudicator has

to keep abreast of any likely demands

on his faculties. He will need a wide

knowledge of instrumental, choral and

vocal music of all grades, the classics

over several centuries, oratorio, opera,

folksong, lieder, and also contemporary

music right up to hair-raising modernities.

He is likely to meet nowadays as much

Bartók as Beethoven, nearly as

much Shostakovich as Schubert, and more

Prokofiev than Purcell.

A very important ingredient

in advancing musical taste throughout

the years is the quality of the words

sung in all vocal and choral classes

in all age groups. As a sort of musical

missionary, the adjudicator is bound

to serve both music and humanity. Yes,

the human side is basic in his work.

A very nervous competitor,

doing badly, even coming to grief, may

be the most musical person in the class.

I myself have many recollections of

an unmistakable appeal coming from a

competitor, youthful or even adult -

a look which says, "I’m horribly

nervous, please help me ..." I

return the look. Vibrations are set

up, and all goes well.

I don’t dare look away,

and I stop writing for fear of breaking

the contact. It’s a sort of miracle

- a quickly-created trio of three active

forces: Music,. Competitor and Adjudicator.

These festivals are

for amateurs, but inevitably the greater

talents appear, from whom many of our

gifted professionals emerge. At this

year’s "Music for Youth" Festival,

the class for Chamber Music Ensembles

was won by a string quartet from Leeds,

aged 15 to 17.

The

adjudicators were deeply impressed with

the near-professional standards of these

young players. They had chosen some

Haydn and Dvořák, and I think you’d

like to hear them playing. Let’s have

part of the Dumka

from the Dvořák String Quartet

in E flat Op. 51 (The Dolce String Quartet).

The rôle of adjudicator

is a pretty complex one. While assessing

and teaching, he has to engage the interest

of competitors and audience, which may

number from fifty to several thousand.

He has to employ tact, and a spice of

humour in season, always trying to preserve

a festive note within each festival.

He has to give a mark for each performance,

a mark which is really a synthetic percentage

of many factors of interpretation and

technique. He has to write an "adjudication"

for each competitor, words of praise

or advice in due proportion.

All entries are voluntary.

So, too, is the devoted work of countless

‘servers’: executives, hall, platform

and adjudicators’ stewards - to say

nothing of subscribers whose financial

help may just convert financial loss

into a slender profit to be carried

forward to the next festival.

Fostered by the British

Federation of Music Festivals, there

are now some 300 competitive festivals

- also non-competitive festivals mostly

conducted by Education Authorities throughout

the country. The Welsh Eisteddfod has

its own special value and character,

as has the Gaelic Mod held every year

in Scotland. Comparison with the standards

of other countries can be found at the

Llangollen International Eisteddfod,

the Tees-side International, and the

International Choral Festival held in

Cork, Ireland. I mustn’t forget the

wonderful chain of festivals across

Canada; or that stupendous festival

in Hong Kong, with its 55,000 competitors

this year.

Now, for our last musical

example, let’s hear a fully equipped

youthful military band - woodwind, brass,

percussion ... the lot. They are the

Croydon Schools’ Wind Orchestra, and

they are going to play the March

from the "Suite in E flat"

by Gustav Holst.

And on that bright,

optimistic note, this adjudicator is

about to stop talking. He would like

to leave you with the thought that the

adjudicator is a mixture of teacher,

judge, jury, counsel for the prosecution,

and counsel for the defence - all at

the service of music.

Composition

As indicated on Page

1, there was never any doubt that, among

all his manifold musical interests,

his work as a composer was the activity

closest to his heart. A list of all

his known compositions and arrangements

totals about 450 (including collections).

Almost two-thirds of his works were

for the human voice - cantatas, solos

or choral - the remainder ranging over

orchestral, piano solo, two-piano or

piano for four hands, one instrument

and piano, chamber music, and organ.

Here, with a few annotations,

is the list of his more important or

most performed works, prepared for the

Grove website:-

Works by Maurice Jacobson

Cantatas

The Lady of Shalott (Tennyson).

1942.

A Cotswold Romance (concert

version of Vaughan Williams’ opera "Hugh

the Drover"). 1951. A performance

by the LSO and London Philharmonic Choir,

under Richard Hickox, was issued as

a CD by Chandos Records in 1998.

The Hound of Heaven (from Francis

Thompson). 1953. David Willcocks conducted

the first performance of the work with

the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra on

November 16th, 1954).

(Family has composer’s own piano and

vocal scores of each of these, with

some of his performance notes.)

Ballet

David (for Markova-Dolin company,

1936).

Orchestral

David Ballet Suite. Alternative

title: Concert Suite (four movements

from music for the ballet). 1949. First

performed by the Scottish National Orchestra

in 1950. Also a version for piano solo.

Lament for Strings (in memory

of Harry Plunket Greene). 1941. Also

versions for piano solo and for viola

or cello and piano.

Prelude to a Play. 1947. Also

a version for two pianos.

Symphonic Suite for Strings.

First performed by the Hallé

under Sir John Barbirolli at the Cheltenham

Festival in 1951.

Theme and Variations. 1947.

See also a version for piano duet/two

pianos.

Chamber Music

Fantasy (Fantasia) on

Sea Shanties. (For violin, cello

and piano.) 1939.

Suite of Four Pieces. (Trio

for flute or clarinet or viola, cello

and piano). 1945.

String Quartet, G major. Unpubd.?

Incidental Music

For Old Vic productions of Shakespeare’s

"Antony and Cleopatra", "Hamlet",

"Julius Caesar", "Macbeth",

etc. 1929-31. The scores are untraceable

- believed to have been lost when the

theatre was bombed during WW2.

Broadcast Music

The Woman of Samaria (after

Edmond Rostand’s "La Samaritaine").

1945. MS. Unpubd.

Men of God, radio plays on six

biblical prophets, in which the music

was integral to the scripts. 1946-47.

MS. Unpubd.

Good Friday (one-hour radio

play, John Masefield). MS. Unpubd.

(Family has scripts, orchestral music

and piano accompaniment for each of

these, also the old-style records of

all the Men of God music.)

---o0o---

Of nearly three hundred songs that

Jacobson composed or arranged, the following

are those still most frequently performed:

Choral

Ariel (tenor or soprano with

SATB). 1923; Blow the Wind Southerly

(arr. for unaccompanied SATB); Ca’

The Yowes (Robert Burns); The

Creed, as used in the Queen’s Coronation

service. (From Vaughan Williams’ Mass

in G minor, adapted by MJ for Anglican

use.); Ellan Vannin (arr. for

SATB and for unison choir); Follow

Me Down to Carlow (for three different

choral formations). 1938-1961; Italian

Salad (arr. for TTBB); Jerusalem

(arr. from Parry for five different

choral formations); Let Us Now Praise

Famous Men (arr. from VW in two

choral versions); Silent Worship

(Handel, arr. by MJ in two choral

versions); Six Negro Spirituals (arr.

for SATB); Swansea Town (also

for solo voice and piano); Three

Hungarian Folk Songs (Matyas Seiber,

arr. for SAB); With a Voice of Singing

(composed with Martin Shaw, 1957).

Solo Voice

Boys (Winifred Letts). 1922;

Psalm 23 (from "David").

1936; The Song of Songs (Book

of Solomon). 1946; Swansea Town;

Various Shakespearian songs (mostly

the only surviving music from the Old

Vic productions of 1929-31).

Piano Solo

Capriol Suite (arr. from Peter

Warlock’s original orchestral work).

1939; Also a version for two pianos;

Carousal (dedicated to Louis

Kentner*). 1946; David Ballet

Suite (arr. for piano in four movements).

Unpubl. MS, with composer’s own performance

annotations; The Dumb Show (inc.

directions for mime, from incidental

music for "Hamlet"). 1930;

For a Wedding Anniversary 1939;

Lament 1941; Music Room Suite.

Five pieces, first pub. 1935. Two of

them, Rustic Ballet and Sarabande,

are now published separately; Romantic

Theme (1910) with Variations

(1944). 1946; Variations on a

Theme by Schumann 1930. [* Jacobson

befriended the young Louis Kentner when

he arrived in England from Hungary in

the mid-1930s, and he remained a family

friend thereafter. "Carousal",

which MJ wrote for him and dedicated

to him, was among the piano works played

at concerts during his centenary year.]

Piano Duet and Two Pianos

Ballade (composed for John Tobin

and Tilly Connelly). 1949; Capriol

Suite. (1947?); Lady of Brazil.

1954; Mosaic. 1949; Prelude

to a Play (arr. by composer from

his orchestral work). 1939; Theme

and Variations (arr. by composer

from his orchestral work). The MS, still

unpubd., was discovered in the family

archives during preparations for Jacobson’s

centenary in 1996 and had its first

public performance at one of the numerous

concerts of his music that year. The

two pianists who played it have since

taken it into their regular repertoire.

One Instrument and Piano

Autumn Lullaby (cello). MS,

unpubd ; Berceuse (viola).

1946. OUP; Humoreske (viola or

cello). 1948; Lament (viola or

cello); Margaret’s Minuet (violin).

1943; Salcey Lawn (cello or viola).

1948.

Organ

A Blessing ("Go Forth Into

the World in Peace") - various

choral versions, with organ accompaniment,

composed with Martin Shaw; Elegy

for Organ (in memory of E. Norman

Hay). 1943-44. MS, unpubd; Processional

(arr. by Trevor Widdicombe from

"David" ballet music, for

use as wedding march, etc.). MS, unpubd;

The God of Abraham Praise (Leoni),

arr. for SATB choir with organ accompaniment.

Agreement in 1964 with C.U.P. arranged

for its inclusion in the Cambridge Hymnal.

Principal publishers:

J. Curwen & Sons (Music Sales Ltd);

Elkin; Lengnick; Novello; Augener; Cramer;

Roberton Publications, a part of Goodmusic

Publishing

Jacobson’s cantata

The Lady of Shalott received

unanimous acclaim from eminent critics

of the day. Edmund Rubbra, in Monthly

Musical Record, classed it as "one

of the most poetic and imaginative works

that I have heard for some time".

Dr Thomas Dunhill and Eric Blom both

expressed pleasure that Jacobson was

the first prominent composer to tackle

Tennyson’s poem successfully. Dunhill

said the work "is noteworthy for

vivid imaginative qualities" and

for "music charged with quite touching

expressiveness", and described

the choral writing as "masterly".

Blom, after a performance in Birmingham,

spoke of Jacobson’s musical idiom as

"extraordinarily evocative, sometimes

quite magically so, and exquisite in

its use of subtle colour of harmony

and of sound-values".

But his greatest composition,

in his own and most other musicians’

view, was his large-scale setting of

Francis Thompson’s mystic poem The

Hound of Heaven - spiritually universal

in theme. First performed in 1954 by

the City of Birmingham Orchestra and

Choir, conducted by David Willcocks,

it also received unanimous critical

acclaim... "A work of outstanding

originality and true spiritual perception"

(Alec Robertson, The Listener).

"A powerful and exciting score,

intensely dramatic, with masterly word-painting"

(Stephen Williams, New York Times).

"I hope this remarkable work will

be widely taken up" (W.R. Anderson,

The Music Teacher)

Subsequent performances

included a nationwide Easter Sunday

broadcast in the United States. After

a performance in New Zealand, the critic

of the Christchurch Press commented:

"It is to be hoped that it will

not have to wait for the genius of its

writing to be recognised in Europe before

it gains proper recognition in England

as a major work." So far, despite

the initial praise, this hope has not

been fully realised. Some twenty years

were to pass before the BBC chose the

cantata for a broadcast honouring Jacobson’s

80th birthday. It was transmitted on

January 2, 1976 - exactly a month before

his death. © Michael and Julian

Jacobson, November 2005

The

Music of Maurice Jacobson

---o0o---

This article has been

jointly written by Michael and Julian

Jacobson - respectively, Maurice's

son by his wife Suzannah, a professional

singer, and his younger son by the composer

and pianist Margaret Lyell

A CD of Jacobson’s

music as performed at the Cadouin Festival

is available through Michael Jacobson

at: B.P.1, 24250 La Roque-Gageac (France).

Cost: £7.99 (incl. p&p) per CD.

The price would come well down for bulk

orders. Michael D. Jacobson jacobson@wanadoo.fr

Tel. (0033) 05 53 29 52 27 Fax: ditto

15 28

The CD couldn't include the whole concert

because it had to be kept within the

then maximum length of 74'. Michael

and Julian chose the four more important

items; they are in a slightly different

running order from that at the concert.

Details as follows: 1. Suite of

Four Pieces. Trio for piano,

cello and clarinet. (Respectively, Julian

Jacobson, Lionel Morand and Richard

Blewett.) [12'19"]; Published by Augener

in 1946. Copies held by British Library,

BMIC, Royal College of Music, and possibly

BBC. Background: The Suite, also scored

for flute or viola instead of clarinet,

was submitted by MJ in his early years

in a competition for a new composition

for wind and strings. The judges split

the first prize. One of the two winners

was Arthur Bliss with "Conversations"

(today a well-known work). This Suite

was the other winner. Besides this recording

at the Cadouin concert, another performance

available from Michael Jacobson is on

an audio-cassette taped at an 80th birthday

concert for MJ at Brighton in January

1976 (a month before he died) and subsequently

broadcast by BBC Radio Brighton. It

was played by the Capricorn Trio, likewise

for clarinet, cello and piano (the latter,

again, being Julian Jacobson). 2.

Carousal. Piano solo (Julian

Jacobson.) [5'51"]. Published by Lengnick,

1946. Copies held by British Library,

BMIC and BBC. Background: This work

was composed for and dedicated to Louis

Kentner, who was befriended by the Jacobson

family after he arrived in England from

Hungary - about 1935 - and who remained

a close family friend from then on.

MJ was the first President of the Chopin

Society in London, founded in 1971.

After his death in 1976, Kentner was

the next President. Besides the cassette

of a performance (also by Julian Jacobson)

at the 1976 Brighton concert, Michael

Jacobson has a recording of the work

being played by the composer himself.

3. Theme and Variations for

piano duet. (Christopher Black and

Yoko Katayama.) [20'17"] Background:

At the Cadouin concert where it was

premiered, it received a standing ovation.

4. The Lady of Shalott.

The Aire Valley Singers and the local

Cantilène choir, conducted by

David Bryant. Tenor soloist: Leon Cronin.

Piano acc.: Julian Jacobson. [32'10"]

Published by Curwen in 1942. Now with

Music Sales Ltd., who have scores and

parts for hire.Copies held by British

Library and BBC. Background: details

also in the notes just sent to you and

in the full biographical article.

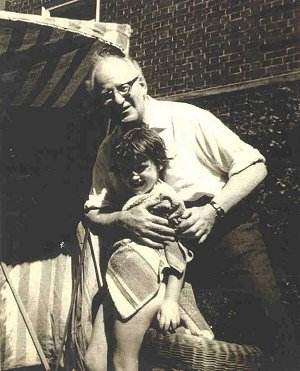

Playing with his granddaughter,

Sallyann (then about 4). This would

have been in the garden of Maurice's

former London home in St John's Wood

(just behind Lord's).