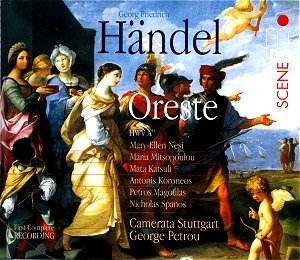

This is not a recording

of a recently rediscovered opera by

Handel. It is a so-called 'pasticcio',

which New Grove defines as "an opera

made up of various pieces from different

composers or sources and adapted to

a new or existing libretto". This definition

demonstrates that there are many ways

in which a pasticcio can be assembled.

Handel's Oreste is a good example.

It was compiled by the composer exclusively

from his own works in 1734 and first

performed in December of that year at

the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in

London.

The music was adapted

to a libretto by Giovanni Gualberto

Barlocci, which is thought to have been

reworked for Handel. He only used arias

from previous operas, whereas the recitatives

were composed especially, as well as

two accompagnati, and probably also

two pieces of ballet music. In her informative

programme notes in the booklet, Annette

Landgraf lists no less than six different

techniques Handel used for the borrowing

and adaptation process: "integration

of the unchanged original, transposition

of the original with the same text,

transposition with a new text, editing

of the source with the maintenance of

the old text, editing of a source and

the underlying of a new text, and, lastly,

the original music with a new text either

taken from the source libretto or completely

rewritten for the already existing music".

The term 'pasticcio'

came into general use only during the

18th century, and at first in a mostly

pejorative way. But, as Curtis Price

writes in his pasticcio article in New

Grove, the practice of putting together

music from different sources was well-known.

In the second half of the 17th century

the demand for opera in Italy was such

that opera companies became increasingly

dependent on revivals of previously

performed operas. And as dramatic works

of the time were usually written for

a specific theatre and with specific

singers in mind, revivals - in other

theatres, and with other singers - forced

companies to change parts of the opera

as written by the composer with music

from other sources which were more suitable

to the actual circumstances and singers.

It was not uncommon to use music by

other composers for that reason, which

made these revivals in fact a kind of

'pasticcio'. Towards the end of the

century this practice became more widespread,

a development which was enhanced by

the fact that in the opera recitative

and aria became less closely connected,

which made it easier to replace one

aria with another. This also led to

a phenomenon like the 'suitcase aria':

singers insisted on replacing arias

in an opera by their favourite arias,

which allowed them to show off, even

though the character didn't fit with

the overall content of the opera.

Perhaps some people

who know their Handel operas will feel

unease at hearing well-known arias in

a completely different context. But

to me this pasticcio sounds like a completely

regular opera. The story is about Oreste,

who, because of his crimes, is pursued

by the Furies and has decided to go

to Tauris to sacrifice himself to Diana.

His sister is Diana's priestess, and

although she doesn't recognize him,

she tries to prevent his sacrifice.

Oreste's wife Ermione, looking for him,

and his friend Pilade are both arrested

by Filotete, who is the captain of King

Toante of Tauris. The reason is that

they are foreigners. Toante has been

told that Oreste will bring him down,

and as he doesn't know Oreste, all foreigners

are arrested to be killed. Toante, who

falls in love with Ermione, is only

willing to spare Oreste's life if Ermione

succumbs to him. She refuses, and when

Ifigenia reveals she is Oreste's sister,

Toante urges her to kill both Oreste

and Pilade. She not only refuses, but

also threatens to kill him. Toante's

captain, who is in love with Ifigenia,

takes her side. A chorus sings "Kill,

kill the tyrant". A fight takes place

and Toante is killed.

In a way it is a shame

that this pasticcio is recorded here

with a cast of singers lacking any 'big

name' from the baroque opera scene.

As a result some people may stay away

from this recording, thinking it must

be 'second rate'. That would be a shame,

as this performance is surprisingly

good, both from a dramatic and a stylistic

point of view. From the singers' biographies

in the booklet one may assume that they

don't have that much relevant experience,

and some of them haven't performed very

often outside their home country, Greece.

If someone has told them how to perform

baroque music, he or she has done a

pretty good job. I have only two critical

comments to make: Maria Mitsopoulou

sometimes uses a little too much vibrato,

and the cadenza of Antonis Koroneos

in his aria 'Vado intrepido' seems to

me a little off the mark. But otherwise

I was pleasantly surprised by the stylish

singing in evidence.

Another one who has

done a great job is the person who was

responsible for the casting. Maria Mitsopoulou

has a strong, clear voice with some

sharp edges, which makes her perfect

for the role of Ermione - a pretty tough

character. Mata Katsuli, on the other

hand, has a much sweeter voice, which

suits the role of Ifigenia very well.

At first I wasn't really moved in any

way by Mary-Ellen Nesi in the role of

Oreste. Though she is in general pretty

good, I occasionally found her singing

a little too flat, for example in the

aria 'Empio, se mi dai vita'.

Toante is a very one-dimensional

character: rude, uncivilised, without

a single sensitive bone in his body.

Even his 'love' for Ermione has no tenderness

at all. Petros Magoulas doesn't try

to hide the unpleasantness of this character

in any way. He gives a perfect portrayal

of the villain of the piece. Antonis

Koroneos makes more impression in the

technical department than as the interpreter

of the character of Pilade. His performance

of the virtuosic aria 'Del fasto di

quell'alma' in the third act is most

admirable, but from a dramatic point

of view his contributions tend to blandness.

I have more or less the same problem

with the male alto Nicholas Spanos,

who has a very nice voice, although

a little soft. When in his aria 'Qualor

tu paga sei' he sings about his love

for Ifigenia, I could imagine a little

more passion than he shows here.

The Camerata Stuttgart

play on modern instruments, but consistent

with historical performance practice

as far as possible. They are quite successful

in that respect, although I didn't like

the overture because of its staccato

articulation and lack of dynamic differentiation.

I have listened to

this recording with a great deal of

pleasure. And I was wondering why these

singers are not better known outside

Greece. I certainly hope to hear more

from them.

Johan van Veen