Jiří

Ignác Linek is hardly a household name.

The first line of the booklet

note on him perhaps points us in the

direction of why: he is ‘a representative

of the musical culture of the Czech

village schoolmasters’. Hardly an incentive

to scurry off and fling the disc into

the machine. Apparently Linek wrote

well over two hundred works, including

a number of Christmas pastorals. His

Sinfonia pastoralis (one of two

of this type: the other is in D and

is available on Supraphon 111007-2)

was probably intended for performance

at his local church in Bakov nad Jizerou

during the Christmas holidays. It is

a bright piece that recalls J. C. Bach’s

Sinfonias. It is eminently civilised

(although, amusingly, a repeated harpsichord

note around 1’10 is rather like having

a nail hammered into one’s forehead!).

The spiky, gallant Adagio leads to a

brief (1’52) Presto that begins happily

enough before ‘Sturm und Drang’ rears

its head. Interesting.

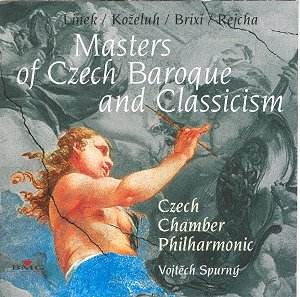

Koželuh

(or Kozeluch as his name is sometimes

found) is perhaps better known, although

not much. Interesting to note that more

Koželuh has appeared recently on the

ever-enterprising CPO label – the oratorio

Moisè in Egitto

(1878: 999 948-2). Koželuh’s career

was more international than Linek’s,

and substantially more successful. He

went to Vienna in the late 1770s and

even refused an offer to become Mozart’s

successor to the Archbishop of Salzburg

in 1781. Immediately it is obvious we

are in a different league from Linek.

The opening is busy, impassioned, with

inner-voice tremolandi generating a

fair momentum and energy. Articulation

in this performance is superb, as is

the Czech Chamber Philharmonic’s responsiveness

to Koželuh’s

dark harmonic colourings. This is a

varied landscape, and leads to a satisfying

experience. Delicious oboes add a special

touch of colour to the hushed Adagio;

the Presto finale is marvellously sustained

here (it is easy to imagine lesser ensembles

allowing interest to flag).

The next stop on this

whistle-top tour of the byways of Czech

pre-Classicism is with F. X. Brixi.

Brixi, son of a Prague organist, wrote

over 500 works (including over 100 masses).

His music was held in some esteem by

Mozart, although on present evidence

it is difficult to see exactly why.

Not that this is bad music – far from

it, it is elegant, brisk and breezy

and most certainly does not overstay

its welcome – but it is surely of no

great import. From 1759, Brixi held

the post of conductor of St Vitus’ Cathedral,

an appointment of very high standing.

The final work in this

disc is by far the best. Antonín

Rejcha (Reicha)’s Symphony in E flat,

Op. 41 simply must be heard. Pupil of

Haydn, teacher of Liszt, Berlioz and

Gounod, Reicha’s music was significantly

more recognised in his day than now.

Until recently he has perhaps been better

known as a theorist, or among wind players

for his works for wind ensemble (try

review

).

The present symphony

dates from his first stay in Paris (1799-1802).

It is beautifully crafted – note how

the Allegro steals in after the Largo

introduction. The imaginative, richly

varied Andante un poco adagio leads

to a gentle Minuet and Trio and a finale

(‘Un poco vivo’) that shifts unpredictably

in its moods.

A fascinating disc

of little-known music, expertly performed

by a top-class chamber orchestra. The

disc seems to be available at mid-price,

a further incentive to purchase. From

the orchestra’s biography, the Czech

Chamber Philharmonic tours mainly in

Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Benelux.

Could they, I wonder, be persuaded to

grace these shores?

Colin Clarke