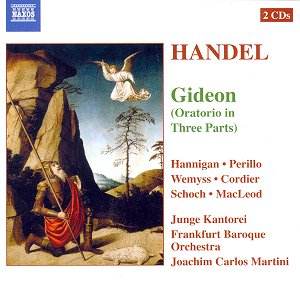

After Handelís death

in 1759 his assistant, the younger John

Christopher Smith, continued the tradition

of regular oratorio performances, in

some cases compiling new works from

the Handel manuscripts he had inherited.

The oratorio Gideon, first performed

ten years after Handelís death, sets

a new libretto by Handelís former collaborator

Thomas Morell. The story deals with

Gideonís destruction of the idol Baal,

the defeat of the Midianites and the

miracle of the fleece. In this it bears

close resemblance to many of Handelís

other oratorio themes. The music used

draws heavily on some of Handelís finest

early works, with a lesser number of

elements (principally Handelian recitatives)

by John Christopher Smith himself. Smithís

close association with Handel certainly

gave him a sure grasp of the masterís

manner of word setting, even if Smiths

own musical gifts were slight.

Among Smithís principal

sources for the arias and choruses are

the great psalm settings Handel wrote

in Rome as a young man; Nisi Dominus

and Dixit Dominus. The latter

work in particular has become very well

known in our own times, but would not

have been so familiar to the staunchly

protestant 18th century London

audience. Smith could have relied on

a certain coup aspect when presenting

this wonderfully vigorous music with

English words and a good Old Testament

story, and indeed it makes the transition

extremely well. The first chorus sets

the manner, using the marvellous Dominus

a dextris movement of the Dixit

Dominus and it was no hard guess

to work out that the final chorus of

the oratorio was likely to be the splendid

closing Gloria Patri of the same

psalm. Indeed, so it turns out, transformed

into a Wonderous are Thy works, O

Lord! with the same Amen as the

original model. These contrafacta give

Gideon an odd sense of familiarity,

disturbed only by the occasional realisation

that the movements are not in the familiar

order.

The recording is a

live performance, with studiously avoided

audience applause, recorded on a single

occasion. As such the quality is commendable.

The singers are uniformly excellent,

although there are a few quibbles. The

high countertenor David Cordier (not

nearly as well known in his native England

as he should be, having made his career

largely in Germany) is one of the few

countertenors capable of handling the

high soprano castrato roles of Handelís

operas. However, some of the writing

here stretches his lower limits somewhat

uncomfortably. The tenor Knut Schoch

sings the title role with generally

excellent English, although there are

occasions where the vowel sounds of

English do seem to cause his vocal sound

to take on a hard edge. However, these

must be viewed as minor quibbles in

a context that is usually excellent.

Certainly the three sopranos are consistently

admirable, especially the delightfully

piquant voice of Barbara Hannigan Ė

a voice that this reviewer would take

out for dinner any time. The Swiss bass

Stephen MacLeod, although having fairly

little to do in the various roles of

a Prophet, a Priest of Baal and Joash

(Gideonís father) sings them all with

appropriately Handelian gravitas and

a consistently rich vocal quality, but

never lacking clarity or focus in the

runs.

The singers are supported

by imaginative continuo, making much

use of the theorbo, (about which one

does wonder slightly, given the 1769

date of the work. This seems rather

too late for theorbo use in performance,

although obviously not for the music

itself, mostly composed decades earlier,

but Smithís venues in late 1760s London

would presumably have been much larger

than those of Romeís private apartments

in which Handel was working in the 1720s,

which does argue against the viability

of the theorbo, as opposed to a decent

sized harpsichord or an organ) and amongst

the players the oboes and the trumpets

and drums are excellent. The string

band of the Frankfurt Baroque Orchestra

is not of the calibre of the better

known Freiburg or Amsterdam Baroque

Orchestras. This is not to say that

there is not quality here Ė the playing

is certainly sprightly, and often expressively

lyrical in the slow movements. The slight

grievance comes in the blending of the

upper strings. Too often there is just

a little too much roughness in the edge

of the sound. This is an aspect that

need not exist given careful orchestral

rehearsal, but one does get the feeling

that the principal rehearsal time is

devoted to the chorus (which is very

competent and frequently exciting),

and the band are assumed to be able

to manage. This is probably perfectly

true, but does make the distinction

between those baroque orchestras that

are made of fine players, and those

that are themselves fine orchestras.

The Frankfurt Baroque Orchestra could

take themselves a level higher.

Given, however, that

there is no other recording of this

work available, one cannot be too picky

about the niceties of string sound polish,

and as this Naxos release represents

the usual excellent value for money

of this label it is hard not to be positive

in recommending this Handel rarity.

It is an enjoyable performance of (often)

familiar music, given an interesting

new flavour.

Peter Wells

see also review

by Jonathan Woolf