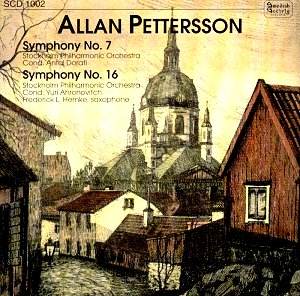

As the messages to this site’s Bulletin

Board demonstrate Pettersson continues to provoke strong feelings.

However one chooses to describe him, adjectivally speaking – and

we all know the kind of things that are said of him – listening

to a Pettersson Symphony at his greatest is one of the most charged,

moving and shaking experiences in late twentieth century music.

And of all the works of his that I know it is the Seventh – in

this by now classic performance – that shakes me the most.

Over the course of its forty-minute span we follow

a symphonic argument of development and rare drama and one that

reveals itself to be profoundly human in its breadth. Listening

to it again for review purposes and writing down scraps of notes

one can see perhaps more clearly that however anguished the language

the structure is firm. From the static opening with those sepulchral

brass to the sense of redirection of energy that is soon generated

we are in the grip of a symphonist of stature. The insistence

of the horn layers from 6’00 and the obsessively frantic drum

tattoos and searing violins open out into a kind of March-Chorale

before the inevitable symphonic catastrophe hits. The lyrical

outburst in response to this assault (just hear how the violins

try to play through the cataclysm) leads to the strings playing

higher and higher as if the very fiddles themselves are striving

for oxygen. It is the consolation of the winds that ushers in

the beautiful, aching string cantilena from 25’00 or thereabouts,

moments of the most extraordinary hope and refuge, real and human

and of terrible beauty. Inevitably the line cannot withstand the

renewed attacks but this time, in time, the fragments of orchestral

sound and colour – flute solos, striding bass pizzicati, wandering

strings – lead to a long-breathed sense of almost-resolution.

Once again the strings soar high up, the lower strings repeat

themselves and a brass figure ends it all. In print it seems schematic;

in practice it is astonishing, a threnody of compelling beauty

and harrowing fissures.

Its companion, the Sixteenth, was his last completed

Symphony and commissioned by the saxophonist here, Frederick L

Hemke. Opening with a jagged and short series of motifs and stern

drum tattoos the rather - and appropriately – sour-sounding saxophone’s

independence of line seems an act of heroism given the mayhem

of motion that buffets and surrounds it. Around 7.00 the orchestral

tumult subsides and we can hear the high winds, which shepherd

the solo instrumentalist through the next stages until a magical

withdrawal of tone at 9.20 – beautiful and ruminative. From 11.50

there is a dramatic accelerando for the saxophone, with a hint

of menace, followed by an uneasy-sounding cantilena. In its concision

and abrupt disjunctions this is a work that fights and refuses

to yield or to go gentle into that good night.

The notes reprint those for the relevant LP issues

of these two symphonies. If you try anything of Pettersson’s let

it be this Seventh.

Jonathan Woolf