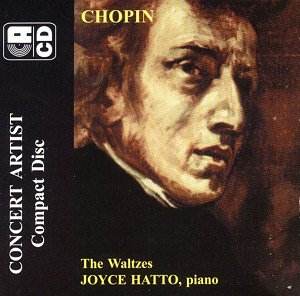

This is Volume 7 in Joyce Hatto’s monumental

Concert Artist series of the complete Chopin piano works.

It’s axiomatic that comparison between two artists

will produce compelling points of divergence but it was most instructive

to listen to her set alongside the paradigmatic Rubinstein traversal

of 1963. In the first, the E flat major, one finds that Hatto

relaxes more into the contrasting central section than does Rubinstein

who is more lithe and excavates a bewitching variety of puckish

voicings. Hatto’s rubato is more pronounced, speeding up and slowing

down, those repeated hammer notes of subtly different speed and

depth; she caresses more, unlike Rubinstein, whose momentum is

straighter; whose line is more undeviating. In the A minor, Op.34/2

we find Rubinstein wistful, espousing recollection in tranquillity

if tinged by regret. Hatto is considerably slower but the differences

between them are not simply ones of tempo because she phrases

and colours and inflects the line with constant rhythmic hesitancies;

in her hands the mood is one of nostalgic reflection.

In the F major (No.34/3) Rubinstein piles on

the colour and crisp accents and humorous voicings (some might

find him just too overtly perky here) whereas Hatto makes the

very most of contrastive material whilst inflecting through rubato

usage. She maintains splendid clarity of passagework in the A

flat major Op.42, relaxing into the central section and then building

to a tremendous climax rather more successfully than Rubinstein.

In the D flat major from the Op.64 set I find that Rubinstein

binds the rhetoric rather more cohesively than she does though

there are many points of interest in the C sharp minor. Rubinstein’s

pointing toward the end is supreme here but earlier we can hear

how Hatto varies the tempo, employing subtle rubati underpinned

by an absolute digital control – excellent passagework. Her sonorities

sound entirely natural and she is a deeply sensitive exponent

of these works sustaining here an air of almost perplexed direction

that is unsettling and thought provoking. In the A flat major

Op.69/1 we again find Rubinstein more obviously ardent, more projective,

kaleidoscopic in his quicksilver emotive responses and also his

ever-present humour. Joyce Hatto employs rubato with considerably

more freedom and doesn’t engage in the kinds of puckish voicings

that the older musician did; hers is a more evidently interior

reading. Sometimes her rubati can seem intrusive – I’m thinking

of the B minor Op.69/2 – but her deep identification with and

projection of the musing central panels of these waltzes can again

be admired in the G flat major Op.70/1. Here this section is very

dreamy and reflective and full of tonal allure and affection.

This is a terrifically difficult waltz and she evinces powerful

command – even Rubinstein smudges a run and I don’t know how many

retakes he had – but on balance he binds the piece more wholly

with no loss of affection. In the posthumous F minor the tables

are turned. Hatto is the quicker, Rubinstein the more pensively

private, Hatto the more heroically public, whereas in the E minor

Op.posth Hatto is not as dramatically powerful or as leonine as

Rubinstein, who drives the waltz with magnetic drama. She is lyrical

and affecting in the E flat major of 1827 and shines undimmably

in the E flat major Op.posth published in 1840. Here there is

true lyrical tonal beauty with animation and colour held in balance

and the direction of the music revealed with unforced lyric courage.

As a bonus there is the F sharp minor Op.posth provisionally dated

to 1835. Joyce Hatto’s notes relate the story of an elderly Priest

having given a copy to the publisher Maurice Dumesnil announcing

it to have been by Chopin; authentic or not it’s a charming close

– and you’ll not often hear it played.

Sound quality is natural and pleasing and the

notes welcome and cogent. Volume Seven upholds the fine standard

set by Joyce Hatto in this series.

Jonathan Woolf

Concert

Artist complete catalogue available

from MusicWeb International