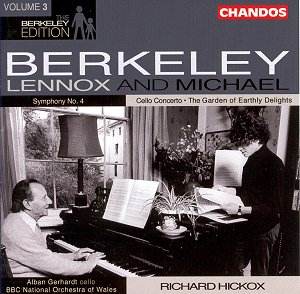

Hot on the heels of

Volume Two comes the third instalment

of the Chandos Berkeley Edition. Into

the bargain we get a further valuable

recording, indeed a premiere recording,

of another Lennox Berkeley symphony.

Berkeley’s own somewhat understated

comment that the Fourth Symphony

is written in "a slightly more

expansive manner" than is usual

for the composer is all the more telling

when one considers the increasing economy

of his later style coupled with the

concision of the one movement Third

Symphony of nine years earlier.

In comparison the Fourth is a fleshier

three-movement affair that has at its

heart a set of variations (a form of

which Berkeley was both fond and a skilled

exponent) juxtaposing elements of slow

movement and more scherzo like material.

The opening movement

begins in hushed mystery on solo bass

clarinet before the Allegro proper is

announced, reaching a brief yet melodically

fulsome climax that returns later, often

in varying guises, but never in exact

repetition (a Berkeley trait). The subsequent

development of the early material is

followed by a final concluding flourish

before the second movement commences

with the theme of the central panel

of variations. Announced by string quartet

and subsequently taken up by the rest

of the strings Berkeley then takes us

through an initially twilit waltz, an

agitated yet ebullient Allegro of contrapuntal

energy, a slowly treading Lento that

has something of the character of a

funeral march rising to a climax before

dying away again, a lively and rhythmically

playful scherzo and a subdued, emotionally

probing Adagio in conclusion. Principally

marked Allegro, the final movement is

centred around the interval of the third

and subjects the opening rising motif

to a variety of transformations before

an emphatic if modest conclusion.

Michael Berkeley wrote

The Garden of Earthly Delights

for the National Youth Orchestra, who

gave its premiere, under the direction

of Mstislav Rostropovich at the 1998

Promenade Concerts. Unlike his father,

Michael Berkeley does not shy away from

orchestral gesture on a serious scale

and the work draws its inspiration from

the triptych by Hieronymus Bosch, utilising

the antiphonal acoustics afforded by

the Royal Albert Hall by placing soloists

at different points around the performing

space. Although the effect of this is

largely lost on CD the music speaks

clearly and powerfully with a number

of thematic cross-references to the

composer’s orchestral work Secret

Garden of the previous year and

included on Volume Two of the series.

The much earlier Cello

Concerto of 1983 was written before

Berkeley’s music took on a greater degree

of astringency in its harmonic and melodic

language, although the composer has

undertaken a number of revisions of

the work, notably in 1997 prior to a

performance at the Presteigne Festival

in Wales, but with further, smaller

scale revision for this recording. Cast

in one continuous but freely changing

span, Alban Gerhardt gives a committed,

technically impressive account and there

is much to enjoy in Berkeley’s often-attractive

melodic writing and vivid orchestration.

That said, I cannot help but feel that

it was not until Berkeley’s music went

through its subsequent stylistic transformation

that he really began to find his true

voice.

As with the preceding

two volumes of the series Chandos have

captured the music in full throated

sound, dynamically impressive and finely

balanced by the engineers. Richard Hickox

draws playing from the BBCNOW that stands

comparison with the finest, all-adding

up to a disc that should grace the collection

of anyone with an interest in British

music.

During a recent chance

meeting with Michael Berkeley, the composer

commented to me that there are further

volumes in an advanced state of planning,

with some material already in the can

and the prospect of a new commission

from Michael himself. Judging by the

results so far, there should be much

to still look forward to.

Christopher Thomas