Comparison recording:

Benda, 6 harpsichord sonatas, Tamara

Franzová. Supraphon SU 3745-2

131

J.C.Mann, 6 harpsichord Sonatas, R.

E. Simpson, harpsichord (2) Initium

CD A001/2

I recently

reviewed a CD of Benda keyboard

sonatas played on the harpsichord by

Tamara Franzová; that disk contains

only two of these 1757 sonatas, so if

you are a Benda completist you will

need both disks.

Benda was born in N.E.

Bohemia, and his father was a weaver

and folk musician. Georg Benda got a

good local education then emigrated

with his family in 1742 to Berlin where

he joined his older brother Frantisek

in the violin section of the Prussian

court opera orchestra. In 1750 he became

Kapellmeister in Gotha where, in addition

to the usual composing of all kinds

of church and secular music for all

combinations of instruments, he also

achieved distinction as a writer of

melodramas, two of which were in Mozart’s

personal library. He failed to obtain

an appointment in Vienna in 1778, and

retired to study and compose in the

town of Köstritz in Saxony.

These sonatas resemble

the harpsichord sonatas of Johann Christoph

Mann (1726 - 1782). Note that the two

men were born within two years of each

other. Both were active in the same

general area of Europe, Mann a native

Austrian based in Vienna but spending

much time in Bohemia. Both wrote clearly

in a North European pre-classical style

in three movements, both wrote for harpsichord

as well as fortepiano, and both men

in their music set out to entertain,

writing in a variety of forms and utilising

songs (Mann uses a Scottish folk song

in his fourth sonata), dances, and even

operatic style settings. Benda is rather

serious; Mann has more fun with his

music. Although Benda was a friend of

C.P.E. Bach, his music resembles that

of the older man only slightly. C.P.E.

Bach’s keyboard music tended to be stiff,

conservative, and somewhat ungracious,

whereas both Benda and Mann wrote very

floridly and eloquently with bold harmonic

colour. The interesting fact is that

the pre-Classical period was more experimental

harmonically than the Classical period

and it is not until Chopin and Schumann

that you see bolder harmonies.

And both composers

are not well known to modern audiences,

yet hearing their music, will teach

you quite a bit about the evolution

of German and Viennese Classical keyboard

style. Some of these movements are almost

pure Bach, some almost pure Mozart,

and there are just hints of Beethoven

and of Domenico Scarlatti here and there.

J.C. Mann used to be

frequently confused with G.M. Monn (1717-1750),

but Simpson’s research has established

their separate identities, although

they may have been brothers. Simpson

uses an electronically sampled MIDI

two manual harpsichord for his Mann

recordings. All the artists use equal

temperament tuning which most people

will probably feel is appropriate, although

I take exception to that and am convinced

that unequal temperament was very much

in use on keyboard instruments even

after 1800. And all the artists use

excellent judgement in ornamentation

— neither too much nor too little. The

performers must receive credit for this

since, although I have not seen the

scores to the Benda, this music is too

early for the ornaments to have been

written out for them in detail. Piricone

receives clear, close recording, and

he does not make use of octave doubling

or register shifts into keyboard ranges

not notated by the composer. Simpson’s

recorded sound is very close, live,

and dynamic, and he makes judicious

use of the coupled 16 foot rank.

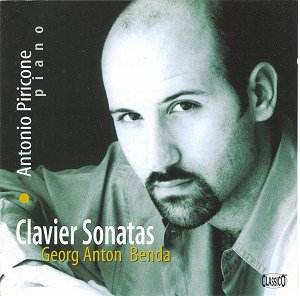

Antonio Piricone, who

is equally renowned as a conductor and

a harpsichordist, includes a thoughtful

essay defending his decision to use

a modern piano for this recording, however

such pleading is hardly necessary. After

only a few bars one is with him all

the way. Piricone’s piano style is clear,

graceful, and non-percussive when that

is called for, yet he plays with drama

and incisiveness when appropriate; we

are not surprised to note that he has

also recorded Bach on the piano to critical

acclaim. With so many really fine recordings

of Domenico Scarlatti on the grand piano

(and perhaps a few real clunkers) the

point should have been made well enough

by now that the interpretative skill

and musical intelligence count for more

than the actual instrument at hand.

And any reasonably aware musician must

have realised that any keyboard music

he wrote after 1750 would end up played

on a pianoforte whether he intended

that or not. Interestingly, Piricone

plays some earlier works than Franzová,

yet both instruments sound equally fitting

to the music. Perhaps because we are

as used to Scarlatti on the grand piano

as on the harpsichord, Piricone’s use

of the piano has the effect of emphasising

the similarities in Benda’s style to

that of Scarlatti, but those similarities

are few. Benda was absolutely his own

man.

There is no information

either in the disk notes nor on the

Piricone’s website listing his teachers;

perhaps like Godowsky (and me) he is

self taught. Simpson studied with Paul

Nettl at Indiana University, played

oboe in the orchestra under Wolfgang

Stressemann, and then studied musicology

at University of Vienna with Schenk.

Initium CDs are available from http://www.initiumcd.com/

Paul Shoemaker