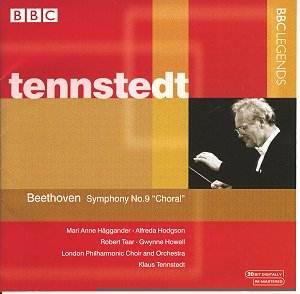

I well remember hearing this performance over

the radio as it happened and being impressed by it then. A friend

who was present at the Albert Hall rang me immediately after it

was over to tell me how amazing it was live. And here it is, available

to all.

Tennstedt was a remarkable conductor, and never

less so than when caught live, as this disc amply demonstrates.

His rapport with the London Philharmonic was a miracle of its

time and it is fully in evidence here.

This Ninth is a far cry from the recent Norrington

on Hänssler . Under Tennstedt, the opening takes on an elemental,

massive quality – here is the Ur-Welt of the beginning

of Rheingold in embryo. This is a statement of the utmost

integrity, an unfolding of organic growth that is entirely true

to the spirit of Beethoven. Tennstedt and his players find astonishing

energy inherent in the harmonies, the orchestra working as one

towards its conductor’s vision.

The ‘live’ element, so visceral in evoking the

tension of the first movement, reveals less than water-tight ensemble

on several occasions in the ‘Molto vivace’ (and it is ‘molto’).

True, some detail gets lost in the acoustic, but there is no doubting

the spirit. Tennstedt takes some 17 minutes over the ‘Adagio molto

e cantabile’ (16’51: contrast Norrington’s 12’07). With Tennstedt

it becomes a gentle unfolding encompassing both grandeur and a

tenderness entirely in keeping with the composer’s Third Period.

Here one enters the near-static world of the slow movements of

the late string quartets, and to mesmeric effect. There is almost

a generosity of lyricism (and such wonderful wind playing!) that

makes the contrast at the beginning of the almighty final movement

all the more effective. Punchy and intimidating, this orchestral

shriek makes its point despite the somewhat strange recording

balance (horns, occasional split and all, shoot through the texture

rather unnaturally).

However one interprets the parade of themes (rejection

versus angry assimilation) that characterises the music pre-‘An

die Freude’ theme, the arrival of the theme itself begins a passage

of natural and inevitable growth that typifies Tennstedt’s organicist

approach. The mighty and powerful orchestral statement immediately

preceding the tenor’s entrance is the only outcome of the (true)

pianissimo cellos and double-basses at 3’.

The soloists are mixed. Howell is fine if not

overly authoritative, and Tear is Tear (overly dramatic and wobbly).

Mari Anne Häggander’s glowing high register is particularly

worthy of note. Soloists are also very closely-miked, leading

to a rather distorted sound-stage. Interpretatively, however,

the performance can hardly be faulted – perhaps the importance

of the line ‘Über sternen muss er wohnen’ is slightly underplayed,

but there is no doubt whatsoever that the rousing cheer from the

Prommers is, for once, thoroughly deserved.

Colin Clarke