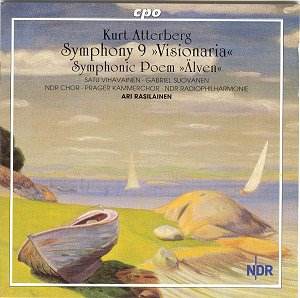

This concludes CPO’s set of the nine numbered

symphonies. The choral Ninth dates from 1956 and is a tough, dark,

often unyielding work. Taking as its text a selection from Volupsá

(The Face of the Prophetess), saga stories steeped in apocalyptic

fatality, Atterberg’s frequently grim introspection also embraces

cataclysm and stasis as well as seriousness and moments of lyric

ardour. Written for baritone and alto soloists – with one duet

– the aesthetic is at times almost remorselessly internalised

but generates a powerful sense of symphonic inevitability. After

the section, an Introduction, marked Beginning there is some expressive

material for the alto before a hieratic, Wagnerian passage for

baritone soloist intrudes but in Väl vet hon we can

hear an almost "speaking" legato, a sense of consolidated,

concentrated power and seriousness which comes before more determined

sectional brass writing, chugging strings and wind, whooping horns

and warlike percussion. His orchestration is relatively sombre

for all these occasional outbursts; a just medium through which

to express feelings both bleak and fearful. The duet between the

soloists acts as a kind of Adagio section with its own saga-harp

interjections and it’s the mezzo soloist who bears the weight

of the increasing pessimism of Mycket jag fattat with its

trumpet and drum powered determination and implacable choral part.

But after the strife and the occasional bludgeoning comes a passage

for solo violin and harp and the baritone’s consoling vision even

though the mezzo, Satu Vihavainen still retains a punishing edge

to her tone and is accompanied by sometimes uneasy orchestral

forces. This is a symphony that can never afford to let down its

guard. Its consolation is accompanied by constant evaluation;

it’s a dark, searing work, complex and forbidding.

All the more apt I suppose that it should be

partnered by Älven – The River – a bright, colourful, wonderfully

warm symphonic poem. This is the Atterberg that most will recognise

– bright primaries, perky, chattering winds, insistent percussion,

wonderful drama and drive and orchestral confidence. Listen to

the lazy shimmer of the Great Lake or the impulsive horns that

announce the Waterfalls as they conjoin with high winds in a long,

big-boned sense of animation and surge. Atterberg seems effortlessly

to summon up expanse and vista and glittering light seen from

afar – and spices things up in the modernistic harbour scene;

all raucous tone painting, horn whoops and Nauticalia. And when

Atterberg leads us Out to The Sea there is real nobility and grandeur.

The ship’s engines are hinted at through the drums as we drive

forward, strings lapping their way around the glorious melody.

The performances are in the main unimpeachable,

though there were some brief moments of questionable choral unison

passages. The works are almost rudely contrastive but constructively

so.

Jonathan Woolf

see also review by

Rob Barnett