This was the first volume to be issued in Malibran’s

Franco-Belgian Violin School series devoted here to two artists

who flourished into the LP era (and in Bobesco’s case beyond into

CD; she is still active I believe). This makes a particularly

interesting conjunction because Bobesco followed Enescu’s path

– Romanian born, French trained – whilst Merckel is more squarely

in the French tradition. Bobesco was born in Craiova in 1921,

a prizewinner at thirteen and an entrant in the Ysaye competition

of 1937. Her sonata partnership with Jacques Genty was long lasting,

as was her leadership of the Ensemble d’Archet Eugène Ysaye,

a position she held concurrently with her professorship at the

Brussels Conservatoire. She was also the first violin of a fine

quartet, which recorded some valuable CDs.

Merckel is one of those French violinists – I

think of Bouillon as well in this respect - whose sterling musicianship

remained broadly for home consumption. Of course he is closely

associated with the native repertoire of which he was such a splendid

exponent, as this disc so amply shows, and if he wasn’t a serious

competitor to his younger French colleague Ginette Neveu it should

be remembered that he was a slightly older contemporary of Francescatti

– and one who took discographic chances with the repertoire in

a way that the more internationally cosmopolitan Francescatti

didn’t. He was above all a frequently marvellous and idiomatic

interpreter of the repertoire and we have some choice examples

to tempt the ear here. So let’s start with him.

His 1946 recording of Pierné’s Impressions

de Music-Hall is full of joyful Gallic wit. Better known,

of course, as a conductor Pierné mined a particularly naughty

vein of popular French music, serving it up in a piquant sauce.

Pugnet-Caillard is similarly engaged in her piano part as the

composer takes us on a brisk scenic tour; the way Merckel coarsens

his pure tone is especially funny – almost as funny as the half

drunken parlando act he essays with such – which makes it all

the better – aristocratic finesse. The Impressions are in the

expected three "movements" – the second of which shows

us the more sentimental side of the Halls, with some impressionistic

blossom and bloom and wistfulness before the final Act which opens

with see-saw vigour to banish torpor and mist. Merckel digs deep

into his eyebrow arching lexicon faithfully to essay the whistles

and sawing fiddles asked of him. I defy you to resist the lugubrious

drunk act which so self pityingly follows, introduced by the ominous

bass in the piano part, with the violin swaying about precariously

until some pulsating virtuosity leads us triumphantly to a close.

Next comes the Intermezzo from Lalo’s Concerto Russe –

truly vital and lively playing if with a slightly metallic edge

to his tone - and the two pieces by Honegger pupil Marcel Delannoy.

The first is the Serenade Concertante, a short work in three movements.

The first, an Allegro, is delightfully verdant and appealing with

little Delian touches flecking the score. The second, an Andante,

floats a delicious series of melodies with wind counterpoint before

growing ever more meltingly affecting in the solo line, songful,

rapturous, only enhanced by Merckel’s aristocratically restrained

but utterly sweet tone. The Capriccio finale is brisk and jovial,

with the solo trumpet imparting a cocksure dance band certainty

to the brew before some little orchestral reminiscences surge

onto a joyful conclusion. The Danse des négrillons

from his ballet La Pantoufle de vair has a swaying rhythmic

finesse. Call it watered down La Création du Monde

if you will but the percussive taps, church bells chimes, violin

doubling the flute line, muted trumpet and exotic strings, impatient

cymbal clash and the like create an atmosphere that’s warm and

appealing.

Bobesco recorded the Symphonie espagnole in 1942

in Paris. She has a rather tense but not unappealing vibrato and

a nicely aerated style. Her trill is not electric but of reasonable

velocity and she employs it well in the Scherzando. She digs into

the chewy lower strings in the Intermezzo third movement (the

one routinely dropped by Russian players), sparing of portamento

– though when she has recourse to expressive devices such as this

she can be charismatic. After Bigot’s rather baleful opening to

the Andante Bobesco plays with well articulated and attractive

intelligence and though some of her phrasing in the Rondo finale

can sound a little smeary and artificial, one must keep in mind

that she was only twenty-one and however talented still at the

embryonic stage of her early career.

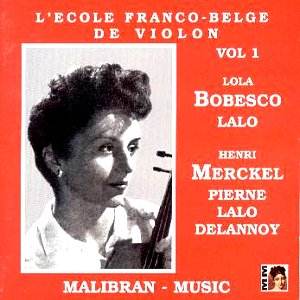

There are attractive period photographs of the

two fiddlers; I liked the no nonsense transfers and obviously

both the repertoire and the musicians are highly congenial to

me. In a sense it’s a shame that Merckel’s own recording of the

Symphonie espagnole wasn’t used – with the Pasdeloup Orchestra

and Coppola - as I don’t think it’s been reissued since and it

would have been a fitting tribute to this idiomatic and now forgotten

musician. But Bobesco makes a good companion and the disc pleased

me enormously. But then Malibran’s string releases always do.

Jonathan Woolf