Faced with such an extraordinary collection of the

flammable and the flighty, one could hardly do other than register the

inimitable singularity of Horowitz’s art. Absorbed into the bloodstream

of this decade’s worth of recordings, these discs present one with limitless

opportunities for ravishment and – yes – revulsion, adoration and abasement.

How could one fail to admire his Scriabin and Scarlatti; how could one

but grin at his perfumed Beethoven; how in microcosmic detail could

one not feel oneself splintered by Horowitz’s own divided self. So many

beautiful things, so many puzzling ones.

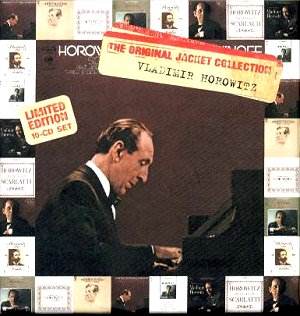

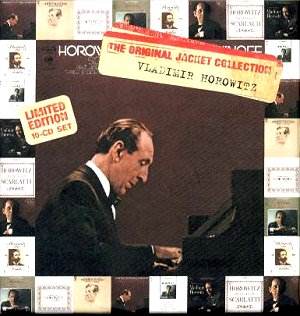

The above represents my own response to this collection

of ten discs entirely replicating, in faithful detail, his LPs of 1962-72.

Many doubtless will still be on the shelves and here they are in miniature

in Sony’s Original Jacket Collection. Each LP has become a CD and my

brief notes must stand for the totality of my response to recordings

now thirty to forty years old. The Sound Of Horowitz gives us

one of the greatest Kinderszenen there has been. Where does one start?

The delicious rubati of Von fremden Ländern und Menschen, the

measured sensitivity of Kuriose Geschichte, the capricious pointing

of Hasche-Mann, the powerful depth of Wichtige Begebenheit,

the truly affecting, entwined depth of Träumerei the

sense, in short, that all is being swept up and engulfed in Horowitz’s

razor sharp romantic responses. Then there is the powerful control of

the Toccata. And Scriabin – the romantic insistence of the C sharp Etude

Op. 2 no. 1, the marvellously passionate and declamatory D sharp minor.

Horowitz plays Scarlatti is one of the great joys of the collection.

He plays twelve sonatas and it’s impossible to choose one performance

to exemplify his aesthetic. But let’s take the A minor, K54 [L241].

This is played with such pellucid beauty, such devastating subtlety,

the left hand never for a moment subordinated, that one can – in the

moment of listening - conceive of it no other way. His Scriabin disc

is frequently incandescent. Vers la flamme (Poème) is

an astonishing vortex of concentrated drama, the like of which one hears

once in a generation. The Tenth Sonata is drenched in the minutest tonal

lightening and colours and an intense directional pull (though there’s

what sounds like a poor edit at 6.40 – not even Horowitz was perfect).

Of course the disappointments co-exist with the rarefied

glory. His Pathétique Sonata is absurdly mannered and

superficial. Who but Horowitz could animate the left hand in the Adagio

cantabile with such inappropriate triviality? Who could be so staid,

so finicky, so plain "wrong" in the Rondo finale? And yet

what follows but Debussy – and one moves from distaste to beauty. I’ve

not thought often of Horowitz as a Debussy pianist and that’s been my

mistake. He plays Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses, Bruyères

and General Lavine – eccentric from Book Two of the Preludes

with capricious and glittering wit; scintillating. Of course there is

Rachmaninov – the G sharp Prelude is grandiloquent and full of powerfully

energised passion, the Etude-tableau in D major courses with leonine

drama, the B flat sonata, the Second, a heroically impassioned landscape.

And of course, Chopin. His Polonaise-Fantasie has pertness

and beauty and limpidity. The A minor Mazurka has a complex wistfulness,

an interior depth and the Introduction and Rondo is marvellously

pedalled – its deceptively benign opening soon gives way to some coruscating

pianism – and utterly bejewelled. And to capture Horowitz in all his

capricious sensitivity there is the A minor Waltz – supremely elegant

playing. (There are moments, it’s true, when his Chopin takes on a rather

lurid hue and I would sympathise with those who find him sometimes less

than candidly expressive in this repertoire). Horowitz at Carnegie

Hall – subtitled An Historic Return, marked his 1965 reappearance

after years of exile from the concert stage. It starts with some rare

Horowitz Bach, albeit hyphenated Busoni. And a little finger slip as

well at the start of the Organ Toccata. His tone in the Intermezzo;

adagio is simply gorgeous – no other word for it – and the withdrawn

pointing of the Fuga memorable. When it comes to Schumann’s Fantasy

there is no chordal hardness at all in the climaxes – even if it

seems to me a less athletic reading than it could optimally have received.

And in the Chopin Mazurka in C sharp Op 30/4 his rhythmic elasticity

is seemingly endless as surely as his command of the first Ballade (G

minor) is total. Here his devilry is accompanied by a searing clarity;

by the time he reaches the concluding Presto con fuoco section

his dramatically high octane pianism has turned molten.

Just some thoughts on the quixotic and extraordinary

pianism contained here. In the unlikely event of some of these discs,

or their reputation, remaining unknown to you I wouldn’t hesitate to

recommend this nostalgic, baffling, devastating, beautiful and frequently

monstrously self-serving collection. In life and in death Horowitz has

a way of bringing out the paradoxical.

Jonathan Woolf