Salome is a great play because it says things

to us that we would resist hearing if presented in simple scientific

discourse. It demonstrates the weakness of religion and the power of

sexuality separated from conventional ideas of love; these are messages

we donít want to hear, even though we already know them. So, Iím saying

that audiences have flocked to Salome for 100 years as a play

and an opera because they donít want to hear what it says? Yes, thatís

it. They need to hear it, but they donít want to. Straussí music amplifies

the play so perfectly that I believe one will find that the play itself

is hardly ever given now, but the opera is given frequently. Apparently

the version without music is now superfluous.

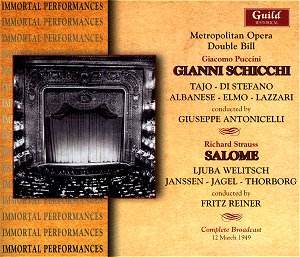

The only Puccini I have really liked is his last and

unfinished opera, Turandot. It is a good experience for a Pucciniphobe

for it demonstrates clearly his genius and how it worked. The first

act is sublime, one of the finest acts in all opera. The second act,

complete, but uneven. The last act is good right up to where the composer

died, and at that moment, where genius left and competence takes over,

as a work of art it dies and it is merely a talented working out, no

genius. Hence, in its lack, we can see in what that genius consisted.

One might, then, imagine my curiosity about Pucciniís next to the last

opera, Gianni Schicchi, the last work he actually completed and

had a chance to hear and repair and work over. On their faces one could

hardly consider two operas less alike, yet both Turandot and

Gianni Schicchi are absurd, allegorical, and both contain moments

of nobility, tragedy, and comedy, albeit in different amounts. Turandot

is more like Salome than it is like almost any other opera, so

this at first inexplicable coupling in this Met program may have an

undercurrent of symmetry after all.

I always listen to a new opera the way I got to know

opera in the opera house before surtitles ó making no attempt to follow

the dialogue, just listening through as though it were an orchestral

tone poem with parts for vocal instruments. Every great opera survives

this kind of listening successfully, and second or third rate opera

does not. A bad opera cannot be justified on the basis of its telling

a good story, and a stupid plot hardly disqualifies an opera from greatness,

e.g., Rigoletto.

The restored sound is quite good throughout, with clear

undistorted voices, little stage noise clutter, no crackle or scratch,

and relatively little congestion at the orchestral climaxes, but still

this is not a hi-fi recording, as we are most seriously aware in the

muddled orchestral climaxes in Salome. Welitschís voice and interpretation

are a wonder throughout, and anyone who knows and loves this opera must

have this version. We are captured by the drama and easily make allowances

for the sonic limitations. The side break occurs at 20.00, at Jochananís

ĎKomm dem Erwählten des Herrn nicht nahe!...í Jagel as Herod is

also a superb actor and fully engages Welitsch for the gripping drama

of the closing scenes. These days of sound characterisations singers

are expected to project their character entirely through the voice.

Kirsten Thorborg sounds enough like Welitsch that you canít tell Herodias

from Salome without following the text. Today this would be a big minus

in a recording; in 1949 it was probably considered good stage technique,

to merge the voices this way.

During this period engineers tended to turn the gain

up and down capriciously and in restoration an effort has been made

to repair this.

This release has also been reviewed

on Musicweb by Robert J. Farr who has knowledgeably discussed which

of the modern performances of Gianni Schicchi one might prefer.

But I think it is obvious that nobody would buy this release as their

only recording of either opera; this is for those who know the opera

and what to hear classic versions.

Paul Shoemaker