The music of the Baltic states continues to fascinate

me hence my decision to review this very recently arrived disc.

Maskats, a Latvian, began composing while at

school. His 1980s were spent in the Daile Theatre - a hard apprenticeship

during which he evolved his own principles for composition. These

were built on his tuition with Valentins Utkins at the Latvian

Academy of Music. He is currently artistic director of the Latvian

National Opera. Despite his theatrical accent he is strongly drawn

to the symphony. His first was written in 2000 and he cherishes

hopes of writing at least four. The Salve Regina, Verlaine

poems and his music for the stage adaptation of that wonderful

novel of jealousy and revenge Thérèse Raquin

won for him the Latvian National Music prize in 1996. Intriguingly

Maskats sees himself in the same landscape as Pärt, Vasks

and Kancheli. His articles of faith include a statement that music

must first of all be beautiful. Maskats is also drawn to dance.

He comments that the nineteenth century and the first half of

the last century had the waltz as their dance hallmark. Maskats

sees the tango as the mark of life in the second half of the last

century into the current century. The Tango is 'life itself'.

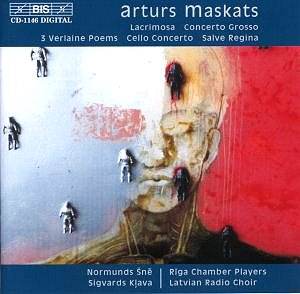

The Maskats works on this CD are all from the

1990s. Three of the five involve the human voice. Two of these

include the chamber ensemble. Both the Lacrimosa and the

Salve Regina are quite short. The latter is for a powerful

mezzo voice, cello and chamber orchestra.

The Lacrimosa was written to mark

the tragedy that was the sinking of the ferry 'Estonia' in 1994.

More than 800 lives were lost. Ethereal female voices enter with

a palpable sense of cavernous space and distance around them.

There is a rasping murmur of strings and moments of awesomely

gothic melodrama for both choir and organ. Other episodes include

the infinitely tender comfort of the singing at 2.53, an underpinning

ostinato like that in Sibelius's Luonnotar and a

Terhenniemi-like mystery (compare Klami's Kalevala Suite).

These are evanescent impressions of a work that instantly tightens

its grip on the listener. My own notes were made before I read

the booklet but I quote from them in relation to the closing moments

of this piece: 'the exhaustion borne of grief.'

The Salve Regina sounds like lyrical

late Tippett in the solo vocal line. The model is perhaps the

baroque cantata - a Bach cantabile fused with a surgingly

melodic energy. The cello speaks for suffering; the voice as balm.

This piece was originally conceived for Reinis Berzieks' cello

with strings. Maskats then came across the ancient Salve Regina

text which seemed a contrasting gemini to the cello's admonitory

grieving.

With a title like Concerto Grosso I

am bound to think back to the Schnittke of the early 1980s ...

and there are some echoes! Maskats' work is in five movements

of which two are buttressing adagios. The work’s origins

are drawn from visits to the Armenian town of Dilijan in which

both Shostakovich and Britten gained inspiration. The sub-title

is Return to Dilijan, itself a variant on the title of

the Albert Camus poem, Return to Tipaz. The two adagios

use a slowly insistent theme for solo violin. This theme is high

and caustic. It conveys the sense of a slow turning in the wind

and then an unwinding; mesmerisingly palindromic like a similar

device in the slow central section of Peter Racine Fricker's Vision

of Judgement. There are neo-baroque episodes, moments that

sound like Vivaldi on steroids, spiritual bell sounds, lonely

acidic violin and cello solos, grinding romantic thunder and a

vertiginous ascent into stratospheric and valedictory silence.

While the notes claim a French approach, with

one exception, I did not hear this and certainly not in Maskats'

setting of Verlaine. Here the writing for the choir

takes us into the ether. The humanising eminence is the grainy

sorrow-sweetness of Normunds Šnē's

oboe solo which appears constantly throughout this most enchanting

of works. There are moments where the inspiration of Šnē,

Maskats and the choir have us wondering at the seamless transition

from oboe to choir and back. There is brilliance in the

middle poem but the flanking sections are ecstatic-reflective

in a way that recalls Debussy's Charles d'Orleans choral

settings.

The five movement Cello Concerto is

an allusive work. Here the allusions are to the two cello concertos

of Jānis Mediņš and to Marija Mediņa (the

daughter of Jēkabs Mediņš and the niece of Jānis).

The soloist here premiered this work and also played the cello

at Marija's request during her last days. The concerto was written

six months after her death. Berzieks premiered the piece

in France in 1992. The work is deeply serious, with a cello part

that is cantorial, often hoarse with sorrow, lugubrious and hieratic.

This is a potently sincere piece the effect of which is amplified

by its relative conciseness. Those who enjoy the named works of

Kancheli (on ECM) and parts of the Sallinen Cello Concerto will

find this well worth hearing.

I am grateful to conductor and oboist Normunds

Šnē for making this review copy available to me. This

approach came about as a result of my reviews of CDs of the music

of Ugis Praulins.

This being a Bis production the notes are in

English, Latvian, German and French although the translations

of the sung texts are only into English. Is English taught as

the prime second subject in Latvia, I wonder.

The experience of Maskats music is res ipsa

loquitur evidence of an entanglement with the expression of

beauty. This is not honey-choked commercialism but certainly stands

at the opposite pole from the sollipsistic universe of academic

avant-garde cliques. Valuable and sincere music with the power

to speak directly.

Rob Barnett

Maskats music is res ipsa loquitur evidence of an entanglement

with the expression of beauty. ... see Full Review