A renowned Mahlerian once good-humouredly took me to

task for, in his opinion, overly favouring recordings from a previous

generation of Mahler interpreters. I donít believe I do that. I try

to take each recording I review on its own merits but when a new one

comes along it has to take its chances against recordings going back

at least to the onset of the stereo era. That is how it is for collectors

these days. Obviously dross is just as likely to come from thirty years

ago as it is today. However, new recordings of Mahler symphonies come

along most months and whilst some are worth the attention of the collector

there are times when someone in my position must point out that someone

from a previous generation seemed to do it better. To me this

never seems truer than in the case of the Third Symphony and this new

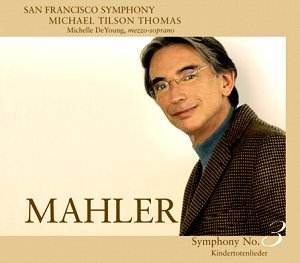

recording by Michael Tilson Thomas in his continuing cycle from San

Francisco illustrates it well. Make no mistake this is a well-played,

well-recorded, enjoyable and involving performance of Mahlerís longest

work. Those collecting this continuing cycle can buy it with confidence.

It is only when it is compared with certain older recordings that you

start to hear what is missing. As I indicated earlier, Tilson Thomas

is not alone in this. I have yet to hear a recent recording of this

particular work that, though possessed of admirable attributes, can

quite compare with recordings that I consider to be the greatest and

which also happen to all come from a generation ago. Horenstein,

Barbirolli, Kubelik and Bernstein (also Jean Martinon in a 1967 Chicago

Symphony recording only available as part of a commemorative set) are

interpreters that come to mind straightaway. Own any two of those in

this work and you will have versions that I believe would last you a

lifetime in purely musical and interpretative terms. If you must have

a supplement in the very latest recorded sound then you could consider

Michael Tilson Thomasís new version, or Rattleís or Gielenís, as all

the earlier ones are showing their age in sound terms.

It takes a particular kind of conductor to turn in

a great Mahler Third. Here is the whole of creation presented in music

as a carefully graded series of steps from primeval inertia at the opening

of the first movement to glittering perfection at the end of the last

Ė primeval sludge to liquid gold. No place for the tentative, certainly

no place for the sophisticated, particularly in the huge first movement

which is so long and so extraordinary in Mahlerís output that its delivery

will absolutely dominate how the rest of the symphony comes to sound.

No place for apologies either in the first movement. You cannot underplay

the full implications of this music for fear of offending sensibilities.

Some of it is banal and "over-the-top"; there is no getting

away from that. Tilson Thomas doesnít fail in this aspect quite as much

as Andrew Litton in his recent Delos recording (DE 3248) who seemed

too often rather ashamed of the music. But there is in the first movement

of this Tilson Thomas recording still not enough of the rough-edged,

rude banality. Iím sure that Mahler meant us to hear this material which

must have so shocked his first audience. This shortcoming is all the

more sharply felt when contrasted with the nature painting Mahler provides

to go with it. Tilson Thomas attends so well to the that aspect. Cases

in point are the great trombone solos, some of the most distinctive

sounds in this movement. In the older recordings mentioned above these

come over almost as a force of nature stressing bloated fecundity. Tilson

Thomasís soloist is a fine musician but his relatively backward placing

in the sound picture to begin with and his largely straight-faced delivery

of this rude and cheeky music is just not powerful or coarse enough

to put across Mahlerís peculiar vision. At one point he does seem roused

to anger, but his contribution passes without too many disturbances

to the landscape. The same applies when the rest of his section joins

him. Under Kubelik, in either his DG studio recording or the superb

"live" performance on Audite (23.403, soon to be reviewed),

recorded in the same week, an unforgettable raw assault bears down on

you like the earth being ripped apart. Horenstein (Unicorn UKCD2006/7)

and Barbirolli (BBC Legends BBCL 4004-7) also pull this effect off.

This is a small aspect, you may say. However I think it indicative of

the overall tone of the first movement under Tilson Thomas which, by

a crucial gnatís whisker, fails to convey what might best be described

as a "life or death" struggle going on. Arnold Schoenberg

heard Mahler conduct this music and referred to a struggle between good

and evil. There must have been something extra-special about that performance

to make him say this. I think the most convincing performances are those

that express this by injecting urgency, even in passages of repose,

to convey the struggle, and also not being afraid to sound ugly when

needed.

Maybe itís the space Tilson Thomas gives the music

in the first movement that makes it fall short on the urgency aspect.

Just over thirty-six minutes is long even for this movement. I can admire

the grandeur, though. Taken with his care for the lyric aspects it certainly

engages right the way through. There are some carefully prepared string

tremolandi in the introduction, and the woodwinds squawk tunefully

on cue every time their dovecotes are disturbed. I always think Mahlerís

birds should be more Alfred Hitchcock than Percy Edwards. This is certainly

the case from Kubelik, Barbirolli and Horenstein (and Martinon whose

Chicago recording demands separate release) and all the better to round

out the picture. The great march of Summer which crosses and re-crosses

the movement is done with gusto and panache, as you would expect from

this conductor, though I found his tendency to over-control detracted

from the "in your faceness" Mahler surely wanted. This march

should just let rip and be its rude self no matter how coarse it might

get. All of this remains the impression to the end of the movement:

grandeur contrasted with lyricism; that means urgency and edge are downplayed

by too much control. Compare with Kubelik and you hear what is missing.

From Kubelik thereís terrific forward momentum, even in the repose passages,

and no lack of the uglier, coarser aspects of nature to go with the

lyric ones. I suppose itís a question of mood and tone and how you perceive

what this first movement is all about. From Kubelik and Horenstein you

get a varied kaleidoscope with no apologies. From Tilson Thomas there

are a few of the colours missing, the primary ones, and not enough sense

of danger.

Tilson Thomasís control of the second movement is strong

too, which gives it an admirably taut quality but then detracts from

the sense of intermezzo that perhaps it should have. There are some

impressive things from the orchestra here, though. The third movement

emerges naturally from the second and is most enjoyable. The post-horn

solo, however, is a little lacking in character, both in sound and delivery.

Beautifully played but no real attempt to "sound-paint" a

mood as so many other conductors do here. Especially good is Horenstein

whose soloist Willie Lang uses a flügel horn. The great coda to

the movement, where nature rears up to bite our heads off, is delivered

splendidly with tremendous portent and fear. Full marks to the horn

section for the lungpower.

Michelle de Young sings the fourth movement with a

matronly operatic vibrato that I didnít really take to. Something more

disembodied is called for here, I think. Whilst the boys in the fifth

movement are pure and bell-like to suit the words I really do miss the

Manchester lads from Barbirolli or the Wandsworth boys from Horenstein

for their sheer cheeky edges.

One of the many appeals of Mahlerís music is how close

it takes itself to edges without quite falling over them. This puts

conductors on their honour to save Mahler from himself when they can.

The Andante to the Sixth always seems to me a step short of kitsch.

Likewise the last movement of the Third seems to me a step short of

mawkish if not handled correctly. Like the slow movement from Brucknerís

Eighth this is, for most of the time, a meditation not a confession.

I think Tilson Thomasís "heart on sleeve" is just too close

to his cuff so the music palls rather. Iím well aware that many of you

will love it and will swoon at this kind of treatment. I wish you well

with it. For me something a little more detached goes a longer way,

saves Mahler from himself, prevents his music being turned into our

own personal psychiatristís couch. At the start of the music part of

me thought I was listening to the opening of Barberís Adagio

and that canít be right at all. Go back to Kubelik for the right balance

of "heart on sleeve" and cerebral repose and you will see

what I mean, even though you might still prefer the Tilson Thomas approach

in the end. Warmth and nobility always win the day here, for me at least.

But thatís not the whole story of this movement, of course. The end

should be triumphant and under Tilson Thomas it really is just that.

The heart is warmed by the journeyís end and this goes some way to making

up for any reservations I may have over the rest. The timpani are in

excellent balance and Tilson Thomas doesnít rush the end like some;

Barbirolli among them, it must be said. In fact I think MTT negotiates

his great ship into harbour with real style and great satisfaction.

No conductor that I have heard has brought off every

aspect of this huge symphony to my total satisfaction and I doubt ever

will. Not even my favourites already mentioned have done that. So Iím

happy to welcome this new recording into the catalogue and stress its

pros rather than its cons. Here the balance sheet is more in credit

than debit. The San Francisco Orchestra is on fine form throughout and

they are recorded with depth and spread in a realistic sound picture

that packs a punch when needed but can pare down to intimacy too. It

must be said that they donít have the last few ounces of tone colour

variation that mark out the greatest Mahler orchestras from the others,

woodwind especially. Their brass section too is rather soulless, especially

when playing all out. But that is often the case with American orchestras.

Tilson Thomas recorded this work once before with the London Symphony

Orchestra for CBS and was much better served by a band that seemed to

know the nooks and crannies of the music more intimately. He was himself

a little more "unbuttoned" then too and "unbuttoned"

is what Mahler was in this symphony.

There is a bonus in this issue of the Kindertotenlieder

sung by Michelle de Young. She delivers them with great imagination

and drama; especially the final song where I have never heard the words

"In Diesem Wetter" spat out with such venom. No one would

buy this issue just for the song cycle but itís a splendid bonus from

one of the best Mahler singers of the new generation who reflects all

aspects of this great cycle with feeling and depth. I just wish I had

liked her in the Third Symphony fourth movement a whole lot more.

A fine recording of the Third well recorded and played

but not quite among the elect. I still await a new recording that will

join those and maybe even trump them. I will be the first to welcome

that day, I assure you. Anybody collecting this San Francisco Mahler

cycle will find it well up to the standard of previous issues.

Tony Duggan