The end of the 18th century saw a gradual

change in the position of chamber music within the classical music

canon. By the early 19th century chamber music came

to be seen as one of the most serious and significant genres.

But in the earlier parts of the 18th century, chamber

music was simply that - music played together in private; music

aimed at good amateurs. Haydn's piano trios of the 1780s reflect

this as the string parts are described as 'obbligato'. This reflects

the tendency of amateurs to add 'ad libitum' string parts to existing

piano sonatas. Haydn's trios from this period, written whilst

he was still at Esterhaza, to a certain extent reflect his recognition

of the taste for amateur performance and his ability to craft

interesting music that was capable of being played by amateurs.

Whilst some of the trios were written for neighbours, such as

the Countess Vizcay, Haydn presumably also had half an eye on

the rather lucrative middle class publishing markets in London,

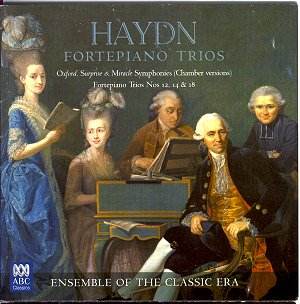

Paris and Vienna. This CD from the Australian group, the Ensemble

of the Classic Era, explores this repertoire by juxtaposing three

of Haydn's piano trios with contemporary arrangements of three

of his symphonies. All the music on this disc can be convincingly

described as being written for intimate performance by amateurs,

rather than the concert hall.

The Piano Trio No. 12 in E minor, Hob. XV:12

was published in 1789 as part of a set of three and newspaper

reviews from this period emphasis the playability of the music.

The opening Allegro moderato is a dramatic and intense movement,

making use of the interval of a tritone. The violin has a tendency

to dominate the ensemble in this movement, and this is a fault

that occurs throughout this set. The Andante cavatina includes

a lovely section for piano and pizzicato strings but the Ensemble

of the Classic Era make rather heavy weather of this, with far

too emphatic pizzicato. The final Rondo is a delightful movement,

tricky in places for the players - the amateurs of Haydn's day

must have been pretty good. The ensemble show moments of rhythmic

instability, something that happens throughout the CD. This is

not a big thing and in a live performance would be quite acceptable,

but is less so in a studio performance.

The Piano Trio No. 14 in A flat major Hob. XV:14

was published in Vienna in 1790 as part of a group of 4 trios

and it was included in performances that Haydn gave in 1792 in

London, the keyboard part being played by Johann Nepomuk Hummel.

These concerts of Salomon's in London are the first known example

of the public performances of Haydn's trios. The opening Allegro

moderato is inclined to the dramatic and includes some nicely

pained dissonances between cello and piano. The beautiful Adagio

includes a central minor section which again uses pizzicato strings.

The piano has some delicate ornaments but the string accompaniment

is again rather heavy handed. This is followed by one of Haydn's

joyously perky finales.

The final trio, Piano Trio No. 18 in A Major,

Hob. XV:18 was part of a group of 4 piano trios that were printed

in London in 1794. This set was dedicated to the widow of Prince

Anton Esterhazy. Prince Anton was the man who had disbanded the

Esterhazy Court orchestra in 1790, thus allowing Haydn time to

travel and capitalise on his enormous reputation abroad. The second

movement is another of those with lovely filigree decorations

in the piano. This movement leads into the gypsy style finale

and the Ensemble of the Classic Era are at their best in this

lively music.

Arrangements of symphonic works for chamber ensemble

are standard currency in the classical era. These enabled people

to get to know works in an era before radio and records. Occasionally

composers could be persuaded to arrange their own works. When

this happens, for example in Beethoven's own arrangement of his

4th symphony, the resulting work is usually interesting

in its own right. But quite often the works are simple hack work,

taking the path of least resistance and providing a rather lacklustre

transcription. In the case of the transcriptions on this disc,

Symphony no. 92 (the 'Oxford') was done by the composer Jan Ladislav

Dussek and he had the confidence to re-work the music for the

new ensemble. The remaining two transcriptions are by Johann Peter

Salomon and are pretty conservative.

Whilst one can but admire Dussek's skill in reducing

the 'Oxford' symphony down to a piano and violin duet, I am not

sure that the gains are sufficient to outweigh the losses. What

is seriously lacking in all three of the transcriptions is that

wonderful variety of tone colour that Haydn could bring to a symphony.

But these arrangements have very different feel to the Piano Trios.

The symphonies rather come over as less subtle, more robust works

with an inevitable amount of padding and the balance between the

piano and the strings is inevitably different to a real Haydn

Piano Trio. The Ensemble of the Classic Era play this music robustly

and convincingly, but the results are a little monochrome.

The Ensemble of the Classic Era are undoubtedly

a talented group and if these were live performances they would

be highly acceptable. But there are occasional moments of unsteadiness.

And I felt a lack of shapely phrasing in the string parts along

with a reluctance to use vibrato even as an expressive device.

Generally the performances of the Piano Trios lacked the grazioso

feel that should be brought to much of Haydn's writing for this

combination of instruments.

This set is probably of greatest interest for

those people who want the transcriptions of Haydn's symphonies.

The performances here of the piano trios are only really adequate

and can be bettered on a number of other CD's. But the transcriptions,

though not interesting enough for the general listener, provide

a valuable document of one of the byways of 18th century

taste.

Robert Hugill