Once lauded as one of the Holy Trinity of Auer students

(along with Heifetz and Elman) Carl Flesch was already sniping

at him in the 1920s and 1930s, asserting that Toscha Seidel more

properly deserved Zimbalist’s place. Indeed listening to Seidel’s

hot blooded and vivacious (if intellectually erratic) playing

is in almost grotesque distinction to Zimbalist’s patrician nobility,

exemplified by his sometimes woefully slow vibrato. Seidel imbued

morceaux with coruscatingly intense life; Zimbalist varnished

them with jewelled aloofness. The latter however could do with

some CDs to his name as befits his importance and this Pearl intelligently

collates his most important recordings – the Brahms and Ysaye,

the only long length commercial discs he recorded, with the exception

of the famous 1915 Bach Double Concerto with Kreisler. It also

includes some of the Japanese sides he made – he was exceptionally

popular there.

The disc starts with his pristine phrasing in

the Beethoven Romance, a performance somewhat vitiated by the

galumphing basses of the Japanese radio orchestra. But it’s the

next two items on which Zimbalist’s meagre heavyweight sonata

reputation rests. The Brahms (recorded in 1930) receives a pliant

and noble reading. Unaggressive in the opening Allegro, with Kaufman

blending well with Zimbalist, whose little subtle rhythmic nuances

are of the greatest interest. We can also immediately hear his

violinistic ethos, his musical-tonal aesthetic, which is analogous

to another Auer pupil, Kathleen Parlow. Neither radiates provocatively

irradiating tonal allure and Zimbalist tends to value lyric generosity

over romantic passion. His ardour, such as it is, is essentially

introspective and one that abjures theatrical flourish. His slow

vibrato is occasionally warmed by expressive power but, in the

main, reflection and a steady architectural surety are his aims.

Of course, as with almost all violinists, he lavishes greater

intensity and colour in the Adagio, calibrated well, affectionate

and aristocratic. His third movement is well characterised – if

the vibrato were faster he might be able to vest it with quicker

wit – though again lacking flourish. The finale has intellectual

clarity and control in profusion, some quick finger position changes

and even though both Zimbalist and Kaufman could be more athletic

it’s a successful performance on its own terms – those of clarity

and refinement and a cool, sometimes dispassionate, objectivity.

The Ysaye Solo Sonata No. 1 in G was dedicated

to Szigeti and its opening recalls Bach’s Sonata in the same key

(a favourite warm up piece of his). The Grave is, in Zimbalist’s

hands, affecting without becoming emotive. He doesn’t dig into

the G string and vibrance is limited but his technical equipment

is fine – some brilliant bowing and left hand pizzicato all negotiated

with nonchalance but not indifference. There’s some swish on the

78 used with does intrude somewhat. If the Fugato isn’t projected

with quite enough drama he phrases the Allegretto with dancing

blitheness and excellent rhythm (albeit slow vibrato in the lower

strings especially). His Hubay Zephyr opens like the clappers

– what kind of wind was blowing in the studio that day in August

1928? – but thankfully he slows down. His trill is excellent,

harmonics tremendous and he doesn’t make an expressive meal of

the contrastive material – he has other architectural fish to

fry. Those wanting a bit of swash and buckle will have to look

elsewhere.

He recorded quite a bit of Sarasate but frankly

Sarasate was not his composer. He is athletic, technically excellent

– bravura bowing and gorgeous trills (Zimbalist was a formidable

technician as we have repeatedly seen) but the slow vibrato limits

both tension and theatrical projection and without them Sarasate

loses impact. The playing is pellucid but lacks titillating colour,

personalisation and, in the end, flair. He promoted Cyril Scott,

as did Heifetz and Kreisler, and plays After Sundown from the

Tallahassee Suite of 1910 with a sweet lyricism entirely in keeping

with Zimbalist’s own aesthetic preoccupations. His own Japanese

confection demonstrates just how big a draw he was in that country

and his Kreisler is an attractive end to this recital.

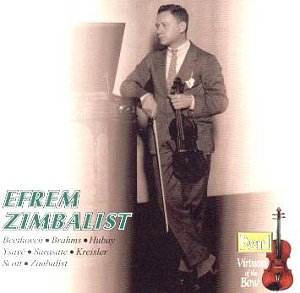

Notes are by well-known collector Lawrence Holdridge

who also made the judicious selection and the cover artwork is

the famous and gorgeously sepia tinted photo of the violinist

listening, fiddle and bow in hand, to a recording on the cabinet

gramophone. The Ysaye isn’t so easy to come across these days

and the Brahms has only been intermittently in the catalogue so,

whatever Carl Flesch may have thought, I strongly recommend acquaintance

with Zimbalist’s nobility and eloquence of expression in this

fine and splendidly transferred disc.

Jonathan Woolf