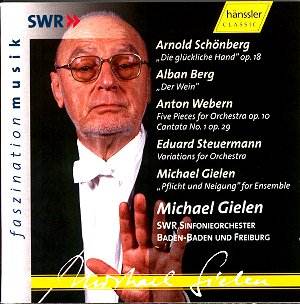

This exceptionally well-filled disc could almost act

as the artistic credo of Michael Gielen. It shows him at his best; as

a conductor in repertoire that no one can better him in, and as a composer

of enviable range and technical skill. The orchestral playing is of

a generally very high standard (as one has come to expect here) and

all soloists try to match their conductor’s vision and commitment.

The programme is both stimulating and logical. It opens

with a piece from the height of Schoenberg’s Expressionist period, where

the harmonies were largely free-floatingly atonal, the melodic lines

angular and the instrumentation exotic and dissonant. The scenarios

from this phase are all angst-ridden or nightmarish. And the nightmares

don’t come much more extreme than Die Glückliche Hand (here

translated as The Blessed Hand, more usually The Lucky, or

Fortunate Hand). This stage drama, written only months after Erwartung,

starts with the following directions, "The stage is almost entirely

dark. A man is lying in the foreground, his face to the floor.

On his back sits a fabulous cat-like beast, a hyena with wings like

a bat, which seems to have its teeth stuck into the nape of his

neck." Maybe it’s this sort of stage instruction, or it only

lasts around 18 minutes, that accounts for the fact that this piece

is rarely performed. Actually, it contains music of great beauty and

subtlety, and was revered by Schoenberg’s followers as one of the best

examples of Second Viennese School thinking at the time. The four scenes

are tightly knit, and it’s good to hear performances of amazing accuracy,

given the difficulty (especially for the chorus) of the chords and melodies.

The orchestral palette is stunning, and Gielen doesn’t miss a trick,

acutely observing the composer’s plethora of markings.

The other works on the disc all seem to follow logically

from this beginning. Berg’s concert aria Der Wein (The Wine)

is a heady, richly dark setting of Baudelaire, and tells of the delights

and perils of intoxication. With instrumental prominence given to saxophone

and piano we get more than a glimpse of Lulu to come, and when

Gielen speaks of the work’s ‘beautiful vulgarity’, he is being complimentary.

It is also tightly organized, and constantly reminds one of the Chamber

Concerto, where the rigours of serial techniques are tempered by

a late-Romantic yearning. The orchestral contribution is outstanding,

though I find Melanie Diener just a shade cool for my liking, particularly

compared with the sensuous sheen of Ann Sophie von Otter for Abbado

(DG).

The Webern Op.10 pieces are right up Gielen’s street,

and his handling of their crystalline delicacy is second to none. No.

4, which lasts a mere 34 seconds, gives us simply three renditions of

the note-row, as if there is nothing more to be said. It reminds me

of a play by Beckett or Pinter, where the silences and pauses are as

important as the notes (or words).

The Cantata Op.29 comes from some 27 years later,

and shows Webern’s mastery of total serialism. What’s really astonishing

is that it actually sounds richer, grander and more romantic than the

earlier pieces. The choral writing is very assured, reminding us of

Webern’s expertise in the field of vocal writing.

Eduard Steuermann was a devoted disciple of Schoenberg

and as his nephew, Michael Gielen, rightly points out, his short, terse

Variations for Orchestra show a style that is ‘something like

a combination of Webern’s brevity and compactness and Schoenberg’s expressive

mood’. You could add Mahler into the mix, but there is individuality

here, and to say Steuermann is best remembered as a pianist (preparing

the premiere of Pierrot Lunaire and making many important piano

reductions) does scant justice to his orchestration which is astonishingly

varied and brilliant. Gielen revels in these colours, coaxing playing

of great range and warmth from his excellent band.

It seems logical to end with a piece by Gielen himself.

It is, by some margin, the longest on the disc (over 25 minutes). The

title Pflicht und Neigung is translated as ‘Obligation and Inclination’,

and the work was premiered in 1989 by Ensemble Modern conducted, of

course, by the composer. It perhaps could have benefited from the sort

of tight compositional procedures we hear in the other works, but still

has enough variety of texture and harmonic interest to just about sustain

its span. It is in three clear parts, of which the most interesting

is the last, where the constantly shifting moods and overlapping sonorities

(from percussion and winds) create an interesting and characterful sound

world. The performance must be considered definitive.

This is a useful and stimulating overview of certain

aspects of central European music through the 20th Century.

It is all beautifully executed and though the recordings span a decade,

they are pretty uniform in their high quality. Booklet notes (by Paul

Fiebig) are of a high order, with illuminating contributions from Gielen

himself. Texts are not included, though Hänssler encourage us to

download from their website. This proves straightforward, and one is

rewarded with full translations in well-spaced, easily readable print.

Highly recommended.

Tony Haywood

![]() SWR Symphony Orchestra

Baden-Baden and Freiburg/Michael Gielen

SWR Symphony Orchestra

Baden-Baden and Freiburg/Michael Gielen ![]() HÄNSSLER CLASSIC

CD 93.060 [78’08]

HÄNSSLER CLASSIC

CD 93.060 [78’08]