The purpose of vocal music (unless as in the case of

Debussy, for example, voices are used as instruments without texts)

is to elevate a text to a level that is beyond the emotional capacity

of speaking. If the musical setting serves the text, then it can be

deemed a success. If it does not, then there was no reason to set it

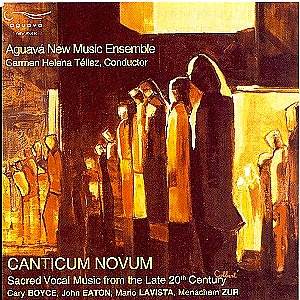

in the first place. In this new recording of vocal music by living composers,

we are met with some definite successes and some abject failures, and

the blame or praise can be laid squarely at the feet of the composers.

Mario Lavistaís 1995 mass setting is a definite success.

In this version, which was recast from its original choral form into

a work for solo voices and a chamber ensemble of instruments, we have

a thoughtful and careful setting of the age-old mass text. It is a setting

that allows for plenty of virtuoso showcasing on the part of the singers,

but at the same time remains true to the intent of the words. One can

quickly conclude that this work probably fares better in its latter

disposition. The vocal lines, while appealing and at times hauntingly

lovely, are beastly in their disjunct melodies and other worldly harmonies.

Carmen Helena Téllez is a conductor with a fine ear for detail,

and she leads a group of first class singing and instrumental talent.

Balances are perfect and these singers handle the difficult vocal lines

with ease. If there be a bone to pick here, it is the annoying mispronunciation

of eleison in the opening movement. The singers consistently

voice the s (making it a z), which is incorrect in either Greek or Latin.

It is a pet peeve of mine and in both mass settings on this disc it

drove me to distraction.

Cary Boyceís By the Waters also receives a fine

performance, but one wonders why so many contemporary composers feel

compelled to put sopranos in the extremes of their ranges for extended

periods of time. Both Bridget Wintermann Parker and Susan Swaney are

human flutes and have amazing control over the purely celestial portions

of their voices, but one is left wondering why they are asked to use

their instruments thus.

To these ears, John Eatonís Mass from 1970/1996 fails.

The extended vocal techniques that the score requires serve no purpose

except to be weird for weirdís sake. The opening Kyrie asks for

most unattractive singing by the female voices, (again with the mispronunciation

of eleison) and the bassís repeated Ky-ri, Ky-ri, Ky-ri, Ky-ri,

Ky-rie sounds a good deal more like the summoning of oneís cat than

a plea for mercy. Of course, some mass settings are intended not for

liturgy but for concerts, but this one fails on both counts. I cannot

find one shred of evidence from listening to this Mass that the composer

had any other intention for the texts than that they were handy and

he did not have to look far to find them. Regardless of intent, the

words of the mass have deep and ancient spiritual meaning to millions

of people. In this case, that meaning eluded the composer.

Menachem Zurís interestingly macaronic setting of Psalm

150 is harmless enough if not completely effective. It is a worthy work

and receives a good performance.

The musicians on this recording are without question

of immense talent and skill. I have to wonder though why such fine talent

is applied to such music. This group would be better served to stick

to composers of Lavistaís ability and leave the others alone. There

is too much fine repertoire out there that never gets the kind of performance

that these musicians are capable of giving.

Sound quality is excellent; program notes are the ramblings

of composer-types who should spare us prose and stick to quavers.

Kevin Sutton