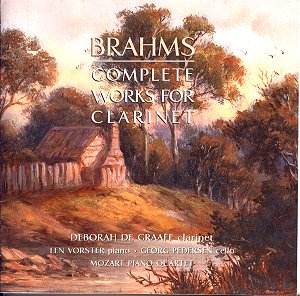

Brahms wrote all these his works late in life. By 1891 the 58-year-old

composer had retired from composition, but his admiration for the playing

of his friend Richard Mühlfeld, a former violinist in the Meiningen

Orchestra, persuaded him to write what are now regarded as being among

his finest chamber compositions. The Quintet is a masterpiece

– a contemplative, autumnal work, in which the broad,

optimistic perspectives of the younger Brahms are replaced by a reflective

melancholy particularly suited to the clarinet. The Sonatas and Quintet,

have rarely been absent from major record catalogues, and today there

is a choice of outstanding performances to which, I am sorry to say,

this set cannot be added.

These are accomplished players, but a closed, unfocused recording does

them no favours, too closely recorded to blend well with either piano

or strings, and not surprisingly there is a certain amount of key-clatter.

In all of them the clarinet has an important share in the counterpoint

and the harmonic, as well as melodic, development of the music, and

in places tends to sound curiously detached from the ensemble. In parts

of the Sonatas de Graaff seems audibly stressed, when her playing comes

dangerously close to stridency and her intonation insecure, particularly

in the high register. In Sonata No.2 the choice of tempi is wayward,

as in the Sostenuto section of the second movement (marked Appassionato,

ma non troppo Allegro in my score and given as Allegretto appassionato

- Sostenuto in the insert booklet)where the haunting, song-like

tune marked piano ben cantando in my score is treated

as a plodding ¾ hymn with disastrous effect.

The players are more at home in the Trio, where the music unfolds naturally

and poignantly, with constantly shifting harmonies. The passages where

clarinet and cello interweave are highly effective. In the Quintet,

however, the self-assertive strings do not treat de Graaff kindly. The

delicate arabesques shared between them and the clarinet in the, Adagio

are handled almost casually, disturbing the unruffled surface of this

wonderful movement. Here also, as in the Sonatas, de Graaff’s tendency

to introduce a swelling of the tone in the high register is superfluous

to requirements. These comments are of course subjective, but for me

it all adds up to several performances short of an extra rehearsal or

two. As any student knows these works take a long time to reach a mature

interpretation: on these discs the potential is there, but too many

golden opportunities are missed for me to rate them highly.

Roy Brewer