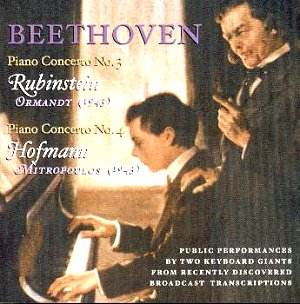

These two live performances were captured for

posterity two months apart in New York. They document a pianist

coming to the end of a glorious career – and in somewhat intermittently

inglorious decline – and another pianist who, though already fifty-seven,

had another thirty years or so of concert giving and recording

ahead of him. Hofmann, whose 1924 Brunswicks are one of the wonders

of the pianistic world, was a famously controversial Beethovenian.

The live 1941 broadcast of the Fourth Concerto with the Philharmonic-Symphony

conducted by John Barbirolli has done the rounds before and is

generally admired. This slightly later broadcast with Mitropoulos

both reinforces and clarifies features of his concerto performances

and does so to considerable, albeit mixed, advantage.

As ever with Hofmann the ear is confronted with

some modulatory bars before the initial piano entry in the Concerto

in G. This was a habit of certain Golden Age pianists but I must

admit I didn’t realise the practice extended to launching thus

one of the greatest works in the repertoire. He is nevertheless

in fine technical form – and one should absorb the hyper-explosive

bass accents he unleashes from time to time in the opening movement

as examples of incinerating, echt Romanticism at its most brazen.

There are highly personalised moments of left-right hand balance

and some Hofmannesque voicings that will catch the unwary off

guard. He plays the Reinecke cadenza. Mitropoulos follows with

incisive commitment; nothing neurotic intrudes. As for the slow

movement, well it’s of considerable interest. Not only does Hofmann

not play synchronous chords – left hand before right was the expected

practice of many pianists of his generation – but he also actually

rolls his chords in the solo piano’s second statement. There’s

touching up and there’s touching up and even for me – one who

basks in the glories of individualised and personalised musical

performance – this smacks of prettifying. His whole ethos here

is in fact very cool, despite this, or because of it. Indistinct

voicings make themselves apparent in the last movement – the melody

line is not always audible – and as he leaps into the cadenza

with a cavalier drive his leonine drama-laced peroration is just

too exaggerated and pleased with itself for genuine musical sympathy.

Highly interesting to hear one of the giants of course but too

idiosyncratic for a general recommendation.

After which Rubinstein comes as a much more central

interpretation - though one not without its own points of interest.

I felt that the first movement of the Concerto in C minor (Music

& Arts have it as the Concerto in C) was rather bedevilled

by Rubinstein’s occasionally self-conscious phrasing. As a result

it lacks a certain amount of inner tension though of itself it’s

quite quick –his rubati are good and his accelerandi somewhat

combustible. I liked the Busoni modified Beethoven cadenza which

Rubinstein despatches with aplomb. It’s doubtless not Ormandy’s

fault that sometimes the bass line sounds muddy and indistinct

– and equally that Rubinstein does sound a little withdrawn in

the Largo. By the fugato episode in the finale the playing is

dashing and there is some finely etched orchestral playing and

if the performance as a whole is rather inconsistent it is at

least consistently inconsistent. Rubinstein recorded the Concerto

five times in all – Toscanini in 1944, Krips in 1956, Leinsdorf

in 1965, Dorati in 1967 and Barenboim in 1975 - though doubtless

other live traversals will turn up.

This has been a most rewarding if occasionally

infuriating listen. The presentation is first class and Gary Lemco’s

notes full of curiosity and interest. If I am less impressed by

the performances than he is then at least he makes his case with

care and judgement.

Jonathan Woolf