AVAILABILITY

www.tahra.com

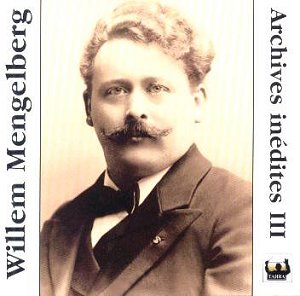

All first releases, this is also Tahra’s final

Mengelberg set in what has proved to be a characteristically personalised

set of performances. The third volume proves to be every bit as

combustible and provocative. The Violin Concerto derives from

a live performance given by Louis Zimmermann in 1940. He is now

an entirely forgotten figure and Tahra’s notes are silent on him

but he was for thirty-five years, barring a small interruption,

leader of the Concertgebouw orchestra. He was also a chamber player

of repute whose only major chamber recording was of the Ghost

Trio with partners cellist Loevensohn and pianist Spaandermann.

He did make two major concerto recordings – the Bach Double for

Decca in 1935 with his fellow leader Hellmann under Mengelberg

and of the work under discussion, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto

on which occasion he was accompanied by an unnamed orchestra and

conductor Woodhouse – a set I’ve never seen or heard of but was

on Dutch Columbia. Zimmermann was sixty-seven in 1940 when he

was recorded with Mengelberg. Many years before, his colleague

Carl Flesch, then living and teaching in Amsterdam, gave a musical

snapshot of him as having a "rounded somewhat weichlich

tone" (weichlich was glossed as "effeminate").

He also accused him of overdoing his portamentos but noted that

as an orchestral player "he was experienced and quick-witted."

One is immediately electrified by Mengelberg’s

highly idiosyncratic orchestral introduction; intensity, balance

(winds vis-a-vis the strings), the strong, uniform string portamenti,

the colossal accelerandi, the brass punctured score. It’s not

perhaps the ideal introduction to Zimmermann’s broken octaves

entry but he is in any case not ideally secure. Indeed this performance,

by a conducting lion of the romanticised and personalised school

and by a venerable leader of the orchestra is an unbalanced one

from the start. Whilst I am immensely sympathetic to him, Zimmermann’s

technique is pretty much in shreds and his tone, never remotely

large in the first place, has long since withered. There are numerous

moments of executant crisis and one awaits the next one with a

certain amount of trepidation. He has a very wavery E, slack lower

strings, hoarse and lacking vibrance. There are some sticky bowing

moments in this first movement and some "noises off"

from the violin in addition to which he bears out Flesch’s admonition

by playing a fairly grotesque downward portamento of considerable

length and maximal gaucheness. Mengelberg rushes the tuttis onwards

– little doubt that he wanted to go even faster than his soloist

and this is by no means a dawdle – but though Zimmermann displays

some intuitive understanding too many things go wrong; painfully

thin and desiccated tone, a decent trill but some problems in

shifts which one should put down to increasing age. Tumultuous

applause however breaks out at the end of the first movement.

Admirers of the Mengelbergian rap on the conductor’s stand will

find new examples of imperiousness here and this is how he starts

the Larghetto. Zimmermann’s rubati are considered and effective,

his musical imagination not unfeeling but limited by tonal variation

and depth. In truth he lacks the lyric line and introspective,

philosophic utterance and seems all too matter of fact. The finale

isn’t really airborne enough – the soloist becoming decidedly

smeary when anything too virtuosic presents itself; Mengelberg

appears rather too emphatic as well. As a performance then, ultimately,

disappointing. As an example of the capacities of an ageing ex-leader

of the orchestra, certainly not without interest and violin fanciers

may well like to hear how Mengelberg’s long-active leader handled

the central repertoire.

The 1936 Seventh was recorded on acetates which

were somewhat damaged. Restoration has meant that these damaged

portions were substituted by the same passages from Mengelberg’s

performance of April 1940. There are scuffs it’s true and some

evidence of aural damage but Tahra’s engineers have done a grand

job. And this is, fortunately, a memorably intense performance.

Of course the caveat should be noted; Mengelberg’s characteristic

wilfulness will offend some ears much as it exults others. This

is vital, driving and inspirational conducting with a first movement

as fast as Toscanini’s almost contemporaneous 1935 Queen’s Hall

performance with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. It exudes striving

and galvanising energy. In the Allegretto he leans very heavily,

creating an almost wilfully ponderous accenting in echt Romantic

style. His stresses and sudden diminuendi are constant features

of his performing style and gloriously – or recklessly, self-aggrandisingly

to doubters – on display here in profuse life. And yet when it

comes to the Fugato section everything is well articulated. The

third movement is perhaps less well negotiated. It emerges as

rather stop-start; or, to put it another way, the elasticity of

his rubati rob the movement of structural integrity. There is

some heavily emphatic playing which is enormously italicised.

And yet, once again, when it comes to the concluding Allegro con

brio, what combustible, dramatic and gloriously life-enhancing

melodrama erupts! His accelerandi – so admired, so reviled – are

a wonder, whatever one’s view may be of their ultimate value.

They are part of Mengelberg’s emotive weaponry of choice and employed

here to devastating effect.

The first CD of this slimline double includes

the Second and Sixth Symphonies. The Second dates from May 1936

and apart from a rather muffled acoustic and some scuffs has survived

in excellent state. Again compared with more central interpretations

Mengelberg can tend toward extremes. He encourages great weight

of string tone in the first movement and some thunderous contributions

from the timpani. In the Larghetto he is slow, much slower than,

say, Erich Kleiber in his rather earlier 1929 commercial recording;

but Mengelberg manages to stress Beethoven’s Haydnesque antecedents

here with striking directness. Listen as well at 2.30 where the

string entries are coloured and laced with intoxicating romanticism

and as ever the wind choirs are to the front of the aural perspective.

The strongly accented Scherzo is followed by a finale notable

for intoxicating crescendos, piping winds, elegant strings and

pure adrenalin.

The Pastoral receives a reading of pure

colour and verdant drama. The first movement is drenched in vivacious

and percussive drive, sudden dramatic sforzandi lacing the score.

The rhythmic tension, the rubati and expressive portamenti all

conjoin in an intensely personalised exploration. His Andante

molto mosso is actually not as slow as one might have predicted

– but it arches with gloriously extensive colour and dynamism,

the clarinet solo delicious in its limpid tracery. The Allegro-presto

is full of the most thunderous bass sonorities and intoxicating

drive and when it comes to the Storm we hear an outburst of elemental,

engulfing terror, one of almost Sophoclean tragedy and visceral

depth. These are extraordinary by any standard. The transitions

are all accomplished with highly personalised but intensely convincing

theatricality. The finale is both beautiful and artfully galvanised

and by the conclusion Mengelberg has seemingly summoned up the

very earth itself.

I found these performances exhilarating and the

presentation, whilst brief, is apposite. The sound is really excellent

and you need have no fear on that account. Some thunderous individuality

may concern those not versed in Mengelberg’s autocratic personality

but to those who have heard the call he is as wonderfully idiosyncratic

and unpredictable, as sonorous and coruscating, as ever.

Jonathan Woolf

![]() Louis Zimmermann

(violin)

Louis Zimmermann

(violin) ![]() TAHRA 420-21 [2CDs:

151.10]

TAHRA 420-21 [2CDs:

151.10]