A typically uncompromising Harnoncourt package with

no. 2 placed first (it was written before no. 1), no concession

to crass economics in the form of a filler to the short second

disc (though this team would surely have raised sparks with the

Choral Fantasia), and no mention on either the cover or in the

booklet that some of us poor vulgar souls have been calling no.

5 the "Emperor" ever since Beethovenís contemporaries

gave it that nickname.

My feelings about this set evolved in the course

of listening to it and Iíd better say, in case my opening salvo

suggests this is going to be a carping review, that this is a

series of performances which forces us to reassess our attitudes

to Beethoven style, and that can be only to the good.

No. 2 begins with a brusque, furrow-browed opening

gesture, answered with all the gentle sweetness of a Mozart serenade.

Each moment of this exposition thereafter receives maximum characterisation,

and each moment is allowed to have its own particular tempo, rather

than be slotted into a single tempo which is held throughout.

The adjustments of tempo back and forth are a little disconcerting.

Then Aimard enters at a different tempo again and he allows himself

as much if not more freedom as Harnoncourt. However, it sounds

more natural, or normal, and this poses our first question. Pianists

tend to allow themselves the luxury of a flexible pulse because

there is only one of them (or, in the case of a concerto, the

conductor is expected to follow as best he can) and they can work

out their pulse variations in the course of long hours spent practising

at home. Orchestras and chamber groups generally settle for a

constant tempo, or at least only a few pre-ordained changes, firstly

because not all conductors are up to controlling such pulse-flexibility

(not a problem for Harnoncourt, clearly), or are allotted enough

rehearsal time in which to obtain it (also this was not a problem

in the present case, I imagine). Therefore we are not surprised

at Aimardís tempo variations whereas those of Harnoncourt take

some getting used to. It is sometimes suggested that solo pianists

should learn from their chamber and orchestral brethren the virtues

of a steady tempo; it has less often been suggested that orchestras

and conductors might learn to play around with rhythms and tempi

as solo pianists are wont to do. Indeed, precious few conductors

since the days of Mengelberg have attempted this, and the received

wisdom, at least until recently, was that it was a thoroughly

bad practice. If Harnoncourt causes us to reassess this received

wisdom, this can do no harm. Sample the opening of no. 3, with

every phrase separated by elongated rests, so that the music gets

under way only gradually; Beethovenís score has been virtually

stripped down and reinvented.

Aimard is a pianist more associated with contemporary

repertoire. In Beethoven he is unfailingly fluent and well-phrased

with a light-filled touch that most resembles, among famous Beethoven

pianists of the past, that of Wilhelm Kempff. There is never a

hard or a crude sound to be heard, his piano always sings and

the interplay between the hands is exemplary. He is capable of

both withdrawn poetry and divine rampage; as with Harnoncourt,

controversy is likely to centre around the range of speeds which

he allows to accommodate these extremes.

Harnoncourtís pioneer work in the original instruments

field shows in the short, stabbing accents of the more rhythmic

themes (try the opening of no. 3), or in his tendency to apply

a diminuendo to a chord which is more often held at a constant

volume (hear the second bar of no. 1). He can be brutal, as in

the passage before the pianoís first entry in no. 3. But he can

also be exquisitely tender, encouraging highly poetic phrasing

from his wind soloists. His insistence on non-vibrato playing

from the strings results, not in coldness but in an organ-like

richness. The slow movement of no. 5 offers a sustained example,

but others abound all through.

In general, it can be said that in the first

three concertos Aimard and Harnoncourt give us bristling, furrow-browed

Beethoven where the rhythmic profile of the music demands it,

but instead of maintaining their drive they relax into post-Mozartian

poetry whenever they get the chance. The result is that Beethoven

seems rather less purposeful than we usually think him to be,

and at times I felt I was listening to some such amiable proto-romantic

as Hummel or even John Field. While shedding light on many incidental

passages, perhaps the overall vision has been reduced, even domesticated.

No. 4 is a special case. The pianistís dreamy

opening is taken at face value by Harnoncourt (I rather expected

the tempo to be whipped up at the first forte passage) and their

poetic, evanescent way suggests that they have decided to try

playing the work in the style of Scriabin or Delius, just to see

what happens. And yet, how wonderfully transparent it all is,

the answering phrases between violins and cellos really clear

for once and the piano totally integrated into the texture. I

shall never hear this work again in quite the same way.

No. 5 gets a spacious, romantic conception, with

the outer movements systematically fielding two tempi, one for

the louder passages and a slower one for the gentler moments.

The result seems more the work of a contemporary of Schumann than

of Beethoven. Thus concertos 1-3 and 5 make a logical progression,

from proto-romanticism to full romanticism, with no. 4 standing

apart as a visionary, sublime statement.

The received wisdom of Beethoven interpretation

was laid down in the 1930s by Weingartner for the symphonies and

Schnabel for the sonatas and concertos. The Gospel according to

Weingartner and Schnabel taught that each movement should be driven

through at a constant tempo; as interpreted by many of their successors

this led to a rigidly inflexible pulse. But it was not ever thus.

Weingartner and Schnabel arrived at the dawn of tolerable recorded

sound, but Beethoven performances from such pianists as Eugen

DíAlbert or Frederick Lamond suggest a quite different attitude

to pulse, not unlike that of Aimard and Harnoncourt. A full-scale

investigation into pre-Schnabel Beethoven on record has not been

made, so far as I am aware, yet some of the earliest artists to

record Beethoven were not so far distant in time from the likes

of Czerny and Moscheles who had it from the horseís mouth. So

it is just faintly possible that Aimard and Harnoncourt are recovering

a flexibility which should never have been lost. The sheer fact

that they provoke such thoughts is surely to be judged positively.

So what sort of recommendation can I give to

this finely engineered set? If you are buying your first Beethoven,

I suppose this might be a risky choice, though better that than

some routine professional job. If you think you know these works

well and are prepared to reassess your reactions to them and to

what constitutes a Beethoven style, then you can look forward

to many hours of illumination. My own responses to the concertos

have definitely been enriched. I wonder, though, if these are

performances were not better heard live, since they often depend

on sheer unexpectedness for their effect. Iíll report again in

ten yearsí time!

Christopher Howell

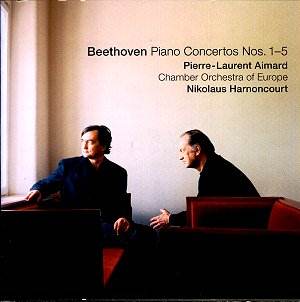

![]() Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano)

Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano)

![]() TELDEC CLASSICS 09274

7334-2 [3 CDs: 70:24, 37:50, 75:09]

TELDEC CLASSICS 09274

7334-2 [3 CDs: 70:24, 37:50, 75:09]