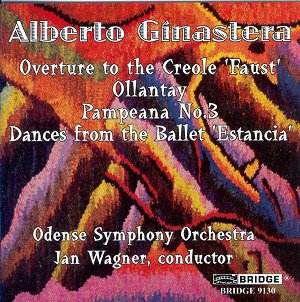

Although there are some important works still

awaiting recording (e.g. the large-scale choral-orchestral Turbae

ad Passionem Gregorianam Op.43, various orchestral works

and the operas), Ginastera’s music has so far been reasonably

well served on record.

Ginastera’s early works were directly inspired

by and influenced by Argentine folk music. This is evident in

the early pieces recorded here. Estancia Op.8 is

Ginastera’s second ballet score and the suite of dances drawn

from it is fairly well known and popular. Many will remember Goossens’

recording release during the LP era. It thus does not call for

many comments. This colourful and rhythmically energetic score

is a sort of Argentine Rodeo (Ginastera studied

with Copland) of which the concluding Malambo is particularly

popular. The Obertura para el ‘Fausto’ Criollo Op.9

is inspired by a poem of the 19th century writer Estanislao

del Campo which tells of a gaucho travelling to Buenos Aires and

attending a performance of Gounod’s opera Faust.

On his way back, he meets an old friend and tells him in his own

words about his operatic experience while sharing a bottle of

gin. Thus, the overture aptly and humorously mixes reminiscences

of Gounod’s score with Argentine rhythms. A short delightful work

and a good example of Ginastera in outdoor mood. It has also been

recorded earlier and many will remember Howard Hanson’s recording

released many years ago on Mercury - it was re-issued in CD format

some years ago. More recently, it has been available in a collection

of short Latin American works (Caramelos Latinos ["Latin

American Lollipops"]) on Dorian DOR 90227.

Ginastera recognised three periods in his creative

output: one of "subjective nationalism" (that of, say,

Panambi and Estancia), one of "objective

nationalism" in which folk elements are transcended in much

the same way as Bartók did in his mature works. The last

which he described as "Neo-Expressionism" relates to

the three operas and the important later works (e.g. the piano

concertos, the cello concertos, the string quartets). The three

symphonic movements Ollantay Op.17 belong to the

second phase. Folk elements are obviously present but no longer

dominate. They are much more integrated into the symphonic argument.

Though inspired by a poem from the early Inca period, it is on

the whole more abstract and eschews any picturesque superficiality.

This substantial orchestral triptych opens with a contemplative,

impressionistic first panel followed by a powerful Scherzo (The

Warriors) and ends with another beautiful slow movement (The

Death of Ollantay). Malcolm MacDonald is right when he writes

that Ollantay is the nearest approach to the symphony

on Ginastera’s part. He is however partly wrong when he mentions

that Ginastera never wrote a symphony. He actually wrote two of

them: the First Porteña in 1942 and the Second Elegiaca

in 1944 though – significantly enough – they were given no opus

number and were withdrawn some time later. Ollantay Op.17

was commissioned by the Louisville Orchestra who premiered it

in 1954 and recorded it on LP (Louisville S-696). Another recording,

in CD format, is available on Largo 5122 (live recording). Though

the present performance is undoubtedly much better in many respects,

the Largo disc may be well worth finding for a complete Panambi.

Ginastera composed three works sharing the title

of Pampeana - a word alluding to the rhythms and melodies

of the Argentine pampas. Pampeana No.1 Op.16 for

violin and piano and Pampeana No.2 Op.21 for cello

and piano are short rhapsodic pieces. The Pampeana No.3

Op.24 is an altogether more ambitious and substantial

orchestral triptych in the same vein as Ollantay.

It too has a central rhythmic Scherzo framed by two slow, expressive

movements. Again, in spite of its title and subtitle (‘Symphonic

Pastoral in three movements’), this is another purely abstract

and tightly argued piece of music. The present performance is

very fine indeed and favourably compares with the late Eduardo

Mata’s reading available on Dorian DOR 90178.

As I mentioned when beginning this review, Ginastera’s

music is fairly well represented in the catalogue, though some

recordings may have passed unnoticed. His present discography

includes several outstanding releases (Naxos 8.555283

[Piano Concertos], ASV CD DCA 944 [String Quartets] and Newport

Classics NPD 85580 [Cello Concertos]). The present release may

safely be added to that list. I hope that we may get more Ginastera

from the present forces. Warmly recommended.

Hubert Culot