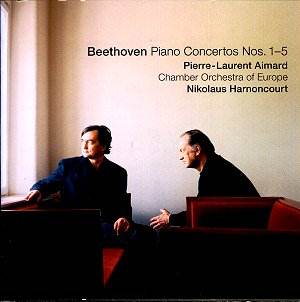

For more than 50 years few classical record collections

will not have included some, if not all, of the Beethoven symphonies

and concertos, and by now most collectors will have their own

firm favourites. Today, however, an increasing number of recordings

provide opportunities for a re-assessment of both familiar and

unfamiliar works. This ‘historically informed’ approach is not,

as some may imagine, an exercise in antique restoration but a

genuine attempt to see these works in the light of current musicological

research, textual analysis and Beethoven’s own dynamic markings.

For the listener the real point of all this is what the music

actually sounds like. Following the enthusiastic reception given

to Harnoncourt’s recently released Beethoven symphonies his interpretations

of the piano concertos have been eagerly awaited, and our patience

has been amply rewarded.

From the opening bars of No. 2 (the first concerto

to be published in a version – much of which is now lost

– and later extensively revised by Beethoven) it is clear

that we are in for surprises, but no shocks. Similarities with

Mozart, particularly in concertos 1 and 2, have occasionally been

noted, but the Beethoven concertos span almost the whole of his

creative life and, as usual, he was doing things in his own way

and in his own time. Overall tempi are not noticeably brisk –

indeed often slower than I anticipated – though the

orchestral texture is more transparent than in the opulent approach

favoured by large, glossy orchestras and star conductors, from

Beecham to von Karajan. The first impression is the amount of

fine detail revealed; the next, and most impressive, is the rapport

between Harnoncourt and Aimard, whose crystal clarity and expressive

brilliance is unfaltering throughout. The piano plays with

the orchestra, not against it as sometimes happens, and this

collaboration allows for greater rhythmic flexibility and integration.

Entries are judged with hairbreadth precision, articulation is

exact and convincing and there is no ‘leading’ or lack of nuance.

Beethoven’s orchestra was, by today’s standards, small, and contained

instruments materially different in sound and volume from those

likely to be found in a modern symphony orchestra. The Chamber

Orchestra of Europe plays, as its name implies, with intimacy,

but no lack of gusto. The dialogue between piano and orchestra

falls naturally and gracefully into an integrated, satisfying

whole that preserves the line of the performance and creates an

enchanting sound world that is distinctively Beethoven’s.

The third and fourth concertos use a musical

language that encompasses the composer’s developing imagination

and sensitivity to the delicate balance between orchestra and

piano. For example, the slow movement of No. 3 is taken at a pace

that gives it the time and space needed for its meditative calm

to unfold, and the slowish opening of No. 4 blossoms like a flower,

with Aimard and the orchestra spinning a magical spell that preserves

its gentle character leading to the vigorous arrival of the first

subject.

It is in No. 5 that we find one of the most finely

wrought and beautifully realised performances on these discs.

Its dramatic opening - usually treated as a flourish

to allow pianists to establish their virtuoso credentials –

is treated less as a fanfare and more as an important part

of the whole movement. Thus through all three movements colour,

excitement, high spirits and mature reflection, arrive with a

sense of inevitability at the brilliant, technically daunting

finale, effortlessly captured by orchestra and soloist. The concerto

is cyclic in form – a ‘symphonic concerto’ in which subtle

thematic interplay is vital – and, once again in this interpretation

we come close to its noble heart.

Whether or not you already possess recordings

of the piano concertos this set will be a revelation of how far

we have moved towards a synthesis between what we expect from

the music and what can still be revealed by dedicated musicians.

Every performance of a work is, in a literal sense, ‘new’, and

I will continue to treasure outstanding, though radically different,

versions of the concertos, such as the 1968 album from EMI with

Barenboim and Klemperer. Such readings are not rendered invalid,

much less obsolete, but it is impossible not to feel that, on

this occasion, we have come appreciably closer to understanding

how Beethoven wanted them played.

In the accompanying booklet Aimard writes ‘Never

would I have imagined that I would one day be recording these

concertos’. We must be grateful that the time has arrived for

him to do so with such manifest success. The booklet also contains

an informative essay by Wolfgang Sandberger.

Roy Brewer

see also

review by Christopher Howell