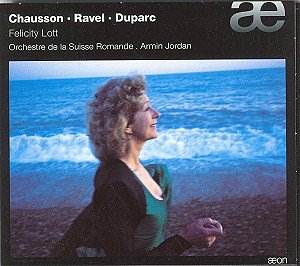

The French label AEON,

though specialising in French contemporary

music, does not neglect classics, albeit

those of the late 19th or

early 20th centuries, as

with the present release.

Chausson’s large-scale

Poème de l’Amour et de

la Mer Op.19, which the

composer dedicated to Duparc, is one

of his unquestionable masterpieces.

This almost symphonic song-cycle on

poems by Maurice Bouchor is a considerable

achievement in its own right. It roughly

falls into two parts (La Fleur de

l’eau and La mort de l’amour

linked by a short orchestral interlude).

The composition of this masterpiece

took Chausson ten years of hard and

painstaking work: the first part was

started in 1882 and orchestrated in

1890 whereas La mort de l’amour

was completed in 1887, although the

closing section of the second part (Le

Temps des lilas) was published separately

in 1886. Chausson’s symphonic preoccupations

are clearly emphasised by the recurrent

statements of several themes ensuring

the organic cohesion of the whole work

which might otherwise have been a mere

collection of songs knit together in

a more or less artificial or superficial

way. The musical phrase, to which the

words le temps des lilas is set,

is particularly important in this respect

(indeed, most of the interlude is based

on it while it keeps surfacing throughout

the whole work).

Henri Duparc’s reputation

rests on a mere handful of beautifully

crafted songs. In this respect, he is

almost unique in the whole history of

music; but this alone would not be enough

to ensure his outstanding position.

His songs, that he painstakingly chiselled,

belong to the finest ones ever written

in France and elsewhere. Some of them,

such as Phidylé

heard here, have become fairly well-known,

popular even, and deservedly so. In

his Baudelaire setting, L’Invitation

au Voyage, Duparc

does not set the central part of the

poem, so that the finished song displays

a clear bi-partite structure, made the

more coherent by the repeat of several

words and phrases (and their musical

equivalents) common to the poem’s outer

sections. In this, Duparc’s setting

is quite comparable with Chausson’s

Poème de l’Amour et de

la Mer, albeit on a smaller,

but nonetheless perfectly achieved scale.

This and the moving Chanson triste

are minor masterpieces.

Ravel’s Shéhérazade,

one of his earliest masterpieces, is

a setting of three poems by Tristan

Klingsor (pseudonym of Arthur Leclère)

that may now seem rather dated, but

that provided Ravel with many opportunities

for either lushly coloured or refined

scoring, which is the trademark of mature

Ravel. Though already displaying a number

of Ravel fingerprints, the music as

a whole still nods towards some of the

composer’s predecessors such as Fauré

or, to a certain extent, Duparc; but

much of this wonderful score is pure

Ravel.

Dame Felicity Lott’s

affinity with the French repertoire

is well-known as is the Orchestre de

la Suisse Romande’s long association

with this repertoire, first with Ernest

Ansermet, later with Armin Jordan. So,

in short, here is a recital of French

orchestral songs performed by artists

with a long expertise of the music.

Add to this, that these works are superbly

recorded; and you will need no further

recommendation.

Hubert Culot