Although composed fifty years ago, about a rural society

which existed fifty years before that, all is clearly recognisable even

today. Lady Bountiful / Billows is alive and well and living in (deeply)

rural England. The excitable local mayor and portentous vicar (now with

a worthy Parish team) survive. The stolid local police superintendent

and the twittering village schoolmistress have gone to an urban environment

in the name of economy. Jack the Lad with his Moll and local children

flourish. Society has changed, but most of the characters, apparently

loved by librettist and composer for the gentleness of their mockery,

abound in village and market town.

That we can share that affection for the characters

on this set is in no small measure thanks to a taut Hickox control of

some very fresh playing by the City of London Sinfonia. Although the

crisp bright sound may be thought ‘thin’ I think that it is entirely

appropriate as the sound of the rural scene.

The Orchestra almost develops its own role as master

of ceremonies of the pastoral proceedings, particularly in some virtuoso

solo and duet instrumental parts. I enjoyed particularly the flute and

clarinet in the Interlude, painting the scene, before Albert’s decision

to rebel.

Of course the problem with a rural society situation,

is that if everyone sang in appropriate accents, most of us would understand

very little. So instead of a Suffolk ‘burr’ everyone sings in good old

dependable BBC English – and there is nothing wrong with that, until

Lady Billows sounds like her housekeeper and sounds like her greengrocer.

That lack of aural distinction is but a small price to pay for clarity

of words.

Without departing far from that, Roderick Williams

and Pamela Helen Stephen, as Sid and Nancy, catch almost perfectly the

characterisation of the butcher’s assistant and the baker’s daughter.

Here are the perfectly matched ‘plotters’. From his entry admonishing

the children to the finale of giving the wreath to Albert, Williams

never falters. There is an insouciance of sound which brings mischievous

Sid sharply into focus.

He is matched note for note by Stephen. Hers is a more

complicated characterisation which comes off superbly: from hesitant

protagonist, through contrition, to indignant commentator on the village

elders’ prurience in the last scene. I enjoyed enormously their duet

(and trio with Albert) leading to "We’ll walk to the spinney…".

This was excellent complementary vocal balance supported by just the

right level of orchestral accompaniment.

Of course before we meet Sid and Nancy, the ‘polite’

society of Suffolk ‘set the scene’ for us in that splendid opening of

English self-importance. Plenty of puffed up balloons here for pricking

and with studied gently accuracy Eric Crozier (librettist) and Britten

miss not a target.

Sally Burgess sings Florence, the all-knowing sergeant

major of a housekeeper. There is a warmth of ‘mezzo’ here which

she holds in check. She delivers her rejections of the nominees with

clarity but perhaps not quite sufficient scorn.

Alan Opie’s round baritone as the vicar is the first

example of luxury casting. As you would expect there is a roundness

of superbly delivered and reasonably unintelligent compassion here.

He seems to float his notes of suggested nominees for Sally Burgess

to shoot down. His "Virtue, says Holy Writ…" is a highlight

with delightfully accentuated rounded vowels, tonal colour and dynamics.

His master of the coronation ceremony is carried off with just the same

apparent effortlessness.

The superintendent is the deep bass of Stephen Richardson.

A judicious slowness of delivery enables him to display the deep filling

sound and maintain clarity of word. That does not disappear when he

speeds up his delivery to profess his preference for ‘a decent murder’.

The twittery teacher, Miss Wordsworth, sung by Rebecca Evans, is not

an easy role – much of it spent in the higher reaches of the tessitura,

making clarity of diction difficult. Unfortunately this is exacerbated

occasionally by a tendency to replace forte with shrill. This

is a pity because where piano applies there is a silkiness of

delivery. Another potentially self-indulgent casting is that of Robert

Tear as Mr Upfold, the self-important mayor. Tear’s recital of his administrative

achievements is delivered with excellent vocal pomposity and if his

participation in the Threnody is loud that is because that is the role.

It is precisely that problem which I think besets Susan

Bullock. We learn from the curriculum vitae notes of the principal singers

in the accompanying booklet that "she is rapidly establishing herself

as Britain’s leading Wagnerian soprano". I refrain from comment

on that as a statement of achievement; but its importance here is voice

–type guidance. I would agree that there is a Wagnerian influence in

the role as it is usually sung. Perhaps one-day some one will say: let

us try the grand lady of imperiousness at piano rather than fortissimo.

Meanwhile, accepting that this is what Britten intended, Bullock’s account

is accurate if occasionally wayward in vowel pronunciation – now standard

English, now Professor Higgins vowels. I am sorry to say that I found

this Lady Billows unconvincing. The booklet refers to her as an elderly

autocrat. Sadly there was little autocracy here and as I said earlier

"sounds like Florence, sounds like Mum". At which point, and

at the other end of the social spectrum, consider Anne Collins as Mum

described merely as "possessive, narrow minded". There is

acidity in her character and even a touch of brutal domination. Again

none of that is readily apparent. The role is sung with total note accuracy

but too much refinement: in "twenty five quid" the word "quid"

jars, as a word that that voice would not use whereas plainly the greengrocer

would use it.

All that leaves Albert and the children. The children

have a difficult small role: sounding very young but singing some difficult

sections, which are pulled off as well as anywhere. James Gilchrist

sings Albert. His is a lighter tenor which goes well with the role.

Consistencies of pronunciation and note accuracy are self evident in

this slightly ‘flattened out’ version of the role. I would have preferred

to hear a slightly greater accentuation of the dominated Albert in contrast

with the freed Albert with more exuberance in the breaking out. Early

on Gilchrist makes him sound as if he has made up his own mind to avoid

sin rather than having his mind made up for him. However after the trio

(with Nancy and Sid) he develops strongly in "He’s much too

busy…" with a superbly delivered hopeless resignation of "for

what". Gilchrist carries well the burden of Act II after the

Interlude with what sounds like total sobriety when a modicum of excitement

would have been helpful.

The ensembles are outstanding. There is an excellent

balance of voices producing some quite delicious blends of sounds. I

would pick out that at the end of Act I as my personal favourite whilst

accepting that the Threnody runs it a very close second.

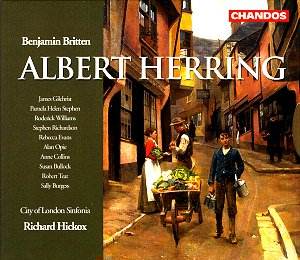

The excellent accompanying booklet with its translations

reminds us of the International appeal of Britain’s favourite (?) opera

composer of the last century. I thought the use of the picture by John

Wimbush of A Vegetable Seller on a Street was an example of first

class presentation and packaging.

In conclusion whilst having one or two less dramatic

moments this recording has some particular strengths and is a very welcome

addition to the Chandos library.

Robert McKechnie