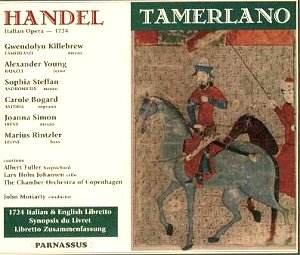

Dating from 1970 and with an almost all-American cast

Parnassus has resurrected one of Handel’s most intriguingly cast operas.

There is a semi-heroic tenor part (taken by one of the non-Americans,

the ever splendid Alexander Young - touching nicknamed "Basil"

by the producers of the set) which is in itself unusual as tenor parts

were generally far less centre-stage and indeed were often parcelled

out to older, less heroic characters. As is also often the case the

theatrical heat really starts to generate as soon as the curtain rises

on Act II and here the succession of arias, if not of the consistency

and melodic and expressive depth of, say, Giulio Cesare is still

quite powerful enough. The arias lead with cumulative force and strength

to one of the most remarkable scenes in Handelian opera, the tour de

force suicide of Bajazet, the captive Ottoman King.

First things first. Recorded then in 1970, in Copenhagen,

and last making an appearance I believe on a four disc LP box [Peerless

Oryx] this will invariably come into some kind of competition with more

recent sets. Gardiner and the English Baroque Soloists essayed it on

Erato back in 1985 and Jean-Claude Malgoire with his Grande Ecurie forces

had beaten Gardiner to it two years earlier. So obvious competition

exists, should these still be in the catalogue (and other contenders

along with them). But don’t write off John Moriarty and his now thirty

years plus recording because this is a consistently well sung and splendidly

astute set that still glitters with imagination and insight.

There are some cuts – noted in the booklet where they

are inset in the printed libretto – and a few arias are shorn of their

da capo sections. Nevertheless Moriarty conducts with splendid understanding;

he’s not as crisp as some might like maybe (I think he’s crisp enough

for me) but his authority can’t be gainsaid and neither can the way

in which he keeps the recitative moving, paying especial attention at

all times to the cadential end lines and making sure these match perfectly

with the vocal line. Young was one of the most sheerly impressive and

stylish Handelians of his or anyone’s generation; the bass Marius Rintzler

shines strongly in his smaller role of Leone. Two of the women’s roles

were originally written for castrati - no countertenors for Moriarty

but we do have mezzos Gwendolyn Killebrew and Sophia Steffan to set

the sparks flying. The Asteria is Carole Bogard and she sings with real

eloquence and brightness of timbre. Joanna Simon makes an excellent

Irene.

There are numerous highlights in the opera. Though

the orchestral introduction is measured Moriarty draws out the woodwind

with aplomb. As Tamerlano, Killebrew has a strong and resonant voice;

it rings at the top and has a defined chest voice adding powerful presence

to her characterisation – her aria Vuo dar pace in Act I Scene

II announces singing of real presence. Steffan’s Andronicus is capable

of the most affecting simplicity; her plangent first Act aria Bella

Asteria is an example of pristine delicacy in the interests of greater

characterisation. Carole Bogard colours and shades her voice with sensitivity

in S’ei non mi vuol amar and there is a directness that I find

immensely appealing about her singing here and elsewhere. Young’s assumption

of the captive King occasions a treasurable example of his versatility

as a singing actor; he manages to exude all the wounded pride in the

world with his elegant insouciance in Cielo e terra armi di sdegno.

The succession of Act II arias represents the heart of the opera;

one after the other the singers are generous and expert. Certainly some

of the ornaments are excessive, some of the runs might with justice

have been retaken but the spirit of the work is wholly present and one

senses them working as a genuine ensemble. Young is splendid in A

suoi piedi Padre esangue – real plangency with expressive orchestration

behind him and the beautiful and revealing trio Voglio stragi for

Tamerlano, Asteria and Bajazet is delightfully sprung rhythmically.

The apex of the incremental melancholy is reached with the final Act

II aria, Asteria’s Cor di Padre which Carole Bogard sings with

genuine distinction.

A dispetto, the Act III vengeance aria has been

sung and recorded by the reigning operatic countertenor of the day,

David Daniels. The orchestration is ebullient, Killebrew herself full

of drama – her low notes well sustained, runs powerfully inflammatory.

The orchestral flutes add a piquant touch to the duet Vivo in te

mio caro bene and the whole suicide scene brings out the very best

in Bogard and Young, a kind of extended pieta of intense theatricality

and power. At the end of this long opera a true sense of the tragic

inevitability of Bajazet’s wished-for suicide has been introduced, sustained

and finally played out. For that the applause must go to performers,

whose sense of ensemble is as sound as their vocal abilities are estimable.

Praise too to continuo players Albert Fuller (harpsichord continuo)

and Lars Holm Johansen (cello continuo). The booklet notes are tasteful

and informative with an Italian-English libretto. Far more famous names

than these have fared far less stylishly and well in Handelian opera

on record and praise to Parnassus for bringing this set back to life.

Jonathan Woolf