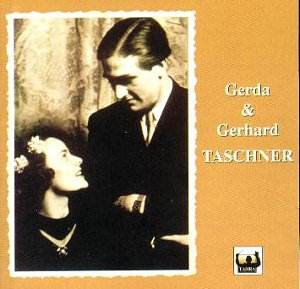

The last few years has seen an explosion of interest

in Gerhard Taschner. A biography, re-issues of his Odeon 78s of the

early 1940s and a number of broadcast performances including major concerti

and work with august collaborators, such as Gieseking, has furthered

our knowledge of his musicianship. His career was truncated and he died

regrettably young at fifty-four, though his active concert-giving career

had trailed off significantly before his death in 1976.

He made his first recordings for Odeon as a young man

of nineteen in war-torn Berlin. Of the eighteen discs that he made ten

are presented in this husband and wife disc devoted pretty equally to

Gerhard and his wife Gerda, herself a talented pianist. Two of the Odeons

include the only sides recorded by Gerhard and Gerda as a duo. His Chaconne,

a massive and etiolated performance, is the work of a serious-minded

young man whose devotion to Bach is not matched as yet by a sense of

architectural responsibility. I’ve previously reviewed a slightly later,

1943 radio broadcast of Taschner’s Chaconne and I thought that was

slow, but this November 1941 performance stretches to a brain curdling

fifteen and a half minutes. His articulation is abrupt, his view romanticised

to breaking point, vibrato intensified in contrastive moments to present

an entirely spurious almost Schumannesque schizophrenia. Italicisation

of phrasing is extreme, the tone not especially beautiful – steely and

undernourished – the conception static, lurching from bar to bar, entirely

introspective with hints of an idée fixe about certain structural

moments, a kind of proto-Franckian one. Well, I am sympathetic to the

concentration and to the powerfully self-absorbed seriousness that Taschner

so enormously conveys and to his relative youth and other maybe external

circumstances – but this can’t, except in a psycho-biographical sense,

be taken as a coherent statement.

The Handel, a recording made two years later, is thankfully

slightly better. He has a nice even trill but a fluttery vibrato that

is not under perfect control. Cor de Groot (what was he doing in Berlin

in 1943?) makes his sonorous presence felt as an accompanist but Taschner

is more grandiloquent than Affettuoso in the first movement and again

very slow with more italicised phrasing, too prayerful at the end of

the movement; the final cadence really does take an age. The second

movement Allegro really isn’t sprung – as a young orchestral leader

he hadn’t yet learnt the trick of conveying internal rhythm. His preparation

for the ritardando is very laboured and the final sudden gush of vibrato

intensification leadenly predictable. There are some good things in

the Larghetto, if sentimental ones and the lack of dynamic variance

in the finale with its clipped articulation somewhat wearying. This

is a Sonata that, spurious or not, fared well on 78s. Thinking of Szigeti,

Menges, Telmanyi and Goldberg amongst others makes it clear that Taschner

was simply not in or approaching that league.

There’s some rather worn sound on the disc of the 1942

Sarasate. It’s a suave, rather over-nuanced performance and not especially

likeable. The Paganini, from the same session, again with his wife at

the piano is not so bad – as Klemperer might have put it. The pizzicati

are good, and there’s rather more animation than was his then youthful

wont but equally there’s no real spark. The disc is rounded out with

a substantial and very big boned and weighty performance of the Piano

Concerto in D given in Leipzig by Gerda Taschner with the Leipzig Radio

Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Hermann Abendroth, one of

only two performances they gave together (the first time in the 1930s

was of the Chopin second concerto). Serious and spacious, with orchestration

of almost Brahmsian weight, this is a frequently grim and rather granitic

traversal. She plays the Reinecke cadenzas however with real verve and

in the Romance second movement fuses poetic introspection and dramatic

extroversion with good results – taking care over her articulation.

No-one can fault Tahra’s dedication to the Taschners

– and the disc begins with a little two-minute spoke reminiscence by

Gerda, still living in Berlin at the time of writing (2003) I believe.

This disc catches Gerhard at the very outset of his career and one should

not expect too much.

Jonathan Woolf