These

recordings were made during the first blooming of the Martinů

revival. The composer, effectively an exile from his homeland,

had died only seven years before the first of these recordings

were made. The seventy-fifth anniversary of his birth passed in

1965. With agonising slowness the then Czechoslovakia began to

produce the Supraphon LPs that acted as emissaries for his music

across the world. In the 1970s these LPs were still in evidence

in record shops and in the UK at the bigger retail chains like

W.H. Smiths who often purchased them in bulk and included them

in their racks during the January and summer sales. Picking up

these Supraphons at between 75p and Ł1.25 broadened not a few

horizons. Of course their poorly translated notes provided easy

scavenging for the critics but their repertoire coverage and the

often vivid quality of the performances won many new friends among

young and impecunious collectors.

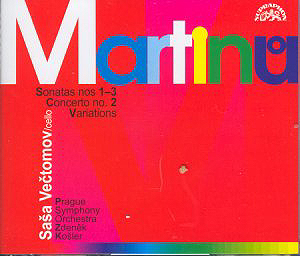

Alexandr

or Saša Večtomov (1930-1989) had distinguished musical forebears.

His father, Ivan, was leader of the Czech Phil. He studied at

the Prague Conservatory with Ladislav Zelenka and completed his

studies with Kozolupov in Moscow. He won many prizes (1955 Spring

Prague; 1959 Casals in Mexico) and toured worldwide with the Czech

Trio. He taught at Prague's Academy of Music.

Josef

Páleníček (1914-1991) has recorded the third and fourth of

Martinů's piano concertos. He was taught in Prague and Paris.

In 1934 he founded the Smetana Trio later dubbed the Czech Trio

joined from 1956 by Saša Večtomov. Between 1949 and 1962

he was often soloist at concerts of the Czech Phil.

The

two artists deliver warm and internalised readings of the three

sonatas. Večtomov's tone is chesty, richly endowed, nasal

and 'sticky' when high in the register. The approach is to accentuate

the melodic so there is a more rounded, undulant contour than

in the very slightly angular readings of Jírí Hanousek and Paul

Kaspar and the spare recording tone on Centaur CRC 2207. These

three sonatas coupled on CD1 are products of Martinů's high

maturity. Večtomov and Páleníček make a grand tragic

statement of the Largo of the Second Sonata displaying

an impressive grip on structure. The singing lines of the Fourth

Symphony reach out from their allegro comodo (tr. 6). The

recording in the Domovina Studio conspires to emphasise the burgeoning

warmth of this music especially noticeable in the last two sonatas.

The First Sonata is by no means the neo-classical frivolity

one might expect from its partly Parisian provenance. It is closer

to the Concerto for Double String Orchestra, piano and timpani.

The Rossini Variations are on a theme from Mose

in Egitto. It was written for Gregor Piatigorsky to a commission.

It is bright, pompous, humorous, hiccuping and ultimately Paganinian

in its showy and storm-tossed leger-de-main. It has its stilly

night as well in the Pierrot moonscape (6.41). The Slovak

Variations were written just six months at the home of

Paul Sacher (who premiered both Gilgamesh and The Greek

Passion) before the composer’s death. This time the theme

(Kebych já vedela, kde môj milý kosí)

is allowed to bloom towards a nostalgic sun. This is one of Martinů's

most concentratedly lyrical pieces. You may have in mind the folk

based piano solos but here he goes further - this is the pastoral

landscape intensified, the composer with head-bowed - reverential.

In the last three minutes rhythmic life floods back with stamping

rhythms and swinging melodic material which occasional reminds

the listener of Szymanowski's Harnasie music.

Večtomov's

Supraphon LP recording of the Cello Concerto No. 2 gained

the Grand Prix Paris' Academie Charles Cros in 1970. Večtomov

premiered the concerto in České Budějovice in May 1965

with the same conductor and orchestra who recorded the work just

over a year later. Martinů wrote the work during his long

American exile between Christmas 1944 and February 1945. His aching

homesickness can at this vantage point be seen as an emotional

counterpart to Rachmaninov's amour lointain for Russia.

Martinů's Czechoslovakia and Rachmaninov's Russia were remote

and unattainable and not just because of geography. The Second

Concerto was the last of his works for cello and orchestra. It

is infused with the natural singing soul of the cello - an accent

apt to Večtomov's innate sympathies. In none of the alternative

recordings does the dancing songfulness of the piece communicate

so well. The cello is recorded closely and makes a lovely sound

though, as with all the 1960s recordings here, without high-end

brilliance or much transparency. In its place there is a surging

fullness of sound - listen to the horn-topped density at 6.40

in the first movement. Ultimately this work suffers a debilitatingly

glorious dose of languor and nostalgia. It is no doubt exactly

what Martinů wanted to say but across almost 40 minutes it

may be just too much of a good thing. If you want only the cello

concertos then Wallfisch on Chandos is your best bet. Otherwise

these warm recordings of most of the cello works is well worth

getting. Večtomov's songful Slovak Variations, the intense

first movement of the Second Concerto and largo of the Second

Sonata are the outstanding highlights of this retrospective.

This

is not the complete cello output. Missing are the Concertino (1924),

Concerto No. 1 (1930, 2nd version 1939, final 1955) and the Sonata

da Camera.

This

set with its slightly congested opaque sound is a treat for Martinů

lovers who want to hear how the two champions of his music developed

a performing style.

Rob

Barnett