The

more unusual offering on this new Supraphon disc is Tchaikovsky’s

Concert Fantasia in G major. Although composed between the 4th

and 5th Symphonies when Tchaikovsky was at the top

of his musical powers, the Concert Fantasia has received very

little exposure. One reason is that the work does not have the

title of ‘Piano Concerto’. Tchaikovsky very much desired this

title, but the two-movement structure mandated a different ‘moniker’.

Another reason is that the form of the work does not carry the

structural or emotional logic one finds in Tchaikovsky’s most

popular creations. Putting matters of structure and title aside,

the Concert Fantasia is a fine piece with many thrilling and stirring

passages and themes.

The

1st Movement of the Concert Fantasia is particularly

rewarding. You won’t find a more exciting and exuberant first

3-˝ minutes of music than offered in the first subject. Also,

this first subject exhibits one of the most compelling aspects

of the great composers, taking the listener to great heights not

thought possible and then raising the bar even further as if a

supernatural mother-ship was propelling us to transcendental wonders.

That’s exactly what Tchaikovsky does in the first subject. His

tremendous surge of energy gets an additional boost when an exploding

piano part punctuated by the orchestra grabs hold of our senses

and electrifies our nerve-endings [tr. 1 2.35].

The

Ardašev version is a fine alternative to the excellent offering

from Mikhail Pletnev. Ardašev and Svárovský impart

greater drive to the Concert Fantasia than Pletnev and Fedoseyev

who are the more exuberant performers. It is essentially a matter

of drive versus lift, and I wouldn’t want to be without either

performance.

The

Concert Fantasia does have its bombastic moments, and Pletnev

plays them to the hilt as if he is competing with the score for

highest number of bombastic points. I much prefer that Ardašev

injects sincere human urges at these moments and largely avoids

the unrealistic and over-wrought route taken by Pletnev.

Pletnev

and Fedoseyev enjoy the superior soundstage. There is an attractive

bloom to their recording that even applies at low volumes. In

contrast, the Ardašev soundstage is rather dry with a noticeable

bloom only taking hold at high volume levels. Overall, the pros

and cons of the recordings and performances tend to balance one

another.

Prokofiev’s

Piano Concerto in G minor is a product of his student period when

he was considered a rebellious student straying too far from the

traditional fold. Critics at the time had a field day when Prokofiev

premiered the work, saying it "has nothing in common with

civilized music" and referring to it as "a Babel of

insane sounds".

Of

course, times have moved on as have musical tastes, and the Concerto

in G minor no longer sounds alien to the enjoyment of music. However,

it is a powerful and stark work with sharp and frantic expressions

mixed with a basic lyricism that wins the day.

Among

its distinctive elements is perhaps the longest 1st

Movement cadenza in any piano concerto written to date. Not only

the longest cadenza, it might also be the most powerful one as

well. At its conclusion, the orchestra led by the brass section

bellows out so strongly that it sounds as if all of God’s fury

is being unleashed upon the Earth. Not surprisingly, this cadenza

is often referred to as the "Cadenza from Hell".

The

2nd Movement is a true ‘moto-perpetuo’ without even

a hint of a rest. This is brilliant material that streaks through

the sky; the form is brittle but never breaks. Brutality takes

center stage at the outset of the 3rd Movement, and

it is easy to understand how stunned that early 20th

century audience might have been. Even more perplexing must have

been the first theme of the 4th Movement with its frenetic

display, which is however given over to a second theme of dark

lyricism.

The

primary reason I cite the comparison versions from Feltsman and

Krainev is their divergent views of the work. Feltsman and the

orchestra prioritize the poetry of the music with some reduction

in conveying its darkest regions and modernist tendencies. Although

a relatively romanticized account, the Feltsman version is very

attractive and possesses fine rhythm. Krainev and Kitaenko offer

us the sleek industrial-strength interpretation, fully bringing

us the technical advances of the early 20th century;

their message is that there is much work to do in order to keep

up with the modern age and no time for sentimental thoughts.

Ardašev

is a cross between Feltsman and Krainev, providing the best that

each has to offer. Sleek and shimmering one moment, powerful and

bleak the next, Ardašev is always at the service of Prokofiev’s

music. I especially love his lyricism and growing urgency in the

second theme of the final movement [tr. 6 2.23].

I’m

not as enthusiastic about Svárovský’s conducting.

He isn’t as willing as Ardašev to plumb the depths of human despair.

He also does not summon that last ounce of all-powerful tension

to the conclusion of the 1st Movement cadenza [tr.

3 10.52].

In

summary, Igor Ardašev is the star of this Supraphon recording.

Born in 1967, he is on the threshold of a wonderful career and

already is receiving frequent praise for his recordings and concert

appearances. I find his Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev performances

outstanding as he displays all the lyricism and rapture called

for in the Concert Fantasia and beautifully blends Prokofiev’s

poetry and spiky rhythms. Overall, he has complete command of

the keyboard and the composers’ idioms. The conducting and soundstage

are not quite up to the high standards established by Ardašev,

but the final verdict is definitely to consider this fine disc

for your music library.

Don

Satz

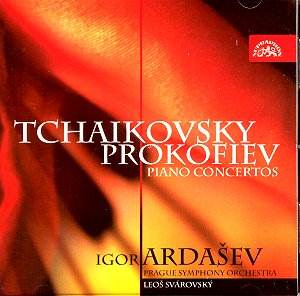

![]() Igor Ardašev, piano

Igor Ardašev, piano ![]() SUPRAPHON 3757-2 [60:58]

SUPRAPHON 3757-2 [60:58]