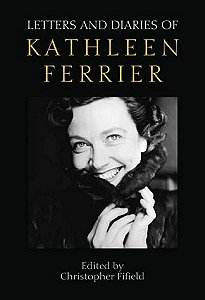

The close of 1953 witnessed the tragic deaths,

in sad succession, of three young performing artists of rising

international stature. Two of these, the pianists William Kapell

and Noel Mewton-Wood, were each only thirty-one years old, barely

begun on the road to fame and greatness; the third, the incomparable

contralto Kathleen Ferrier, while ten years older, enjoyed a professional

career of only similar length: a mere decade or so.

The fiftieth anniversary of Ferrier's death from

cancer is being commemorated in this country by, among other events,

both the recent first release of an off-air performance of Mahler's

Das Lied von der Erde given with Barbirolli and the tenor

Richard Lewis in 1952 (APR5579) review,

and the first publication, in the volume under review, of her

letters and diaries covering the years from 1940 until her death.

There are just over 300 letters, many hitherto

unpublished and deriving from a cache of correspondence discovered

by editor Christopher Fifield in the offices of music agents Ibbs

and Tillett, for whom Ferrier was one of their sole artists. They

are divided into eight chapters, the first given over to the years

1940-47, the others having each a year to itself until 1953. Each

chapter is headed by a vital and informative biographical introduction

provided by the editor. As well as the letters to Ibbs and Tillett,

those most prominent here are to Ferrier's sister Winifred, her

favoured Canadian accompanist John Newmark, her American friends

Benita and Bill Cress, Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears (whose

creativity joined hands with hers in a number of collaborative

artistic endeavours, notably The Rape of Lucretia, the

Spring Symphony and the canticle Abraham and Isaac),

and her beloved conductors John Barbirolli and Bruno Walter.

In all, this correspondence delivers on reading,

in its present format an impact far exceeding the often mundane

nature of its content, which on thr surface is largely concerned

with the daily minutiae oif a touring artist's life. What emerges

is a vivid self-portrait of a brave, secure woman in love with

life and music, whose joie de vivre was palpable and supported

both by a notable lack of inflated egoism and a singular sense

of humour which rarely faltered, even towards the end.

Here is a short example, taken from a letter

to Winifred written from New York during her second trip to America

in 1949, shortly after confronting her agent there and successfully

negotiating a rise in fee for the following year:

To give me courage I bought a new hat, bag,

shoes, stockings and summer nylon pantie girdle, and could

have coped with a whole blinking board of directors. I have

only sagged a little now, having discovered that the tab on

my dress had been sticking out at the back of my neck all

the time. I thought people were looking at me, but I thought

it was admiration!! That'll larn me! (Letter No.112)

I was personally pleased to discover in these

pages, for the first time anywhere, some indication of Ferrier's

involvement with E.J.Moeran's last solo song Rahoon, a

bleak masterpiece which he wrote for her in 1947. Although I had

hitherto assumed, having found no reference at all to the matter

elsewhere, that Ferrier may not actually have performed the song,

it is now clear that she sang it regularly during the years 1948-50,

in tandem with another, very different Joyce setting, The Merry

Green Wood. She even writes out the poem in Letter No.84, though

without prior knowledge one would not know she was referring to

a song by Moeran. This is one instance among others where I felt

the need for an in-text editorial annotation, of which there are

none in the volume. Moeran's name is in fact only included in

the Index of Works: it appears in neither the Personalia nor General

Index.) If only Ferrier had recorded Rahoon!

The Diary section is perhaps of rather less immediate

interest, being simply a daily listing of social appointments,

meetings and concert dates, with occasional personal comments

attached, but never a whisper of self exploration.

It is perhaps best read as an amplification of

the context in which the letters were written, and reveals Ferrier

as far more extravert a person than her recordings lead one to

imagine. As such it helps act as a welcome antidote to the death-surrounded

image so often attached to this artist because of what she sang

(Kindertotenlieder, Das Lied von der Erde, The

Dream of Gerontius for instance) and the way she died.

Anyone interested in Kathleen Ferrier's life

and art and the milieu of the Second World War years and their

aftermath by which they were embraced, will find this welcome

book required reading. It is above all, and despite the final

descent, a celebration of living.

© John Talbot