The Symphonic-Concerto was written during the years

separating the Piano Quintet and the Violin Sonata (both 1935 and both

recorded with considerable panache and gravitas on Timpani) from the

First and Second Symphonies (1941 and 1945 respectively). The work was

premiered in Munich on 26 October 1937 and in Berlin (with Edwin Fischer)

five days later.

There have been a small harvest of recordings of this

work. Furtwängler and Fischer's Berlin premiere spawned a set of

acetates released by Pilz during the 1990s. Barenboim (piano) and Mehta

revived the work in the 1970s. This recording was revival was issued

by Bongiovanni, Phorion and Penzance. There are private off-air tapes

of broadcasts by Paul Badura-Skoda and Dagmar Bella (one of the composer's

daughters). More accessibly there is also a Marco Polo CD (8.223333)

in which David Lively appears with the Czecho-Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra

conducted by Alfred Walter. Walter was a veteran of a 1980s BBC orchestral

cycle of the three symphonies and of recordings on the Marco Polo label.

Of this group I know only the Barenboim/Mehta recording and that in

a now rather gloomy tape copy.

Out of the turbulent, tense banks of cumulo-nimbus

heavy with threat the piano rises to a stonily ringing heroic assertion.

We have a storm-blasted work at least in the typically big first movement.

That movement lasts two minutes more than half an hour; as long as many

romantic concertos! Furtwängler certainly had a template for expression

of his creative urge. That pattern did not admit of brevity. Just look

at the Bayer and Timpani recordings of the chamber music; not to mention

the Warner recording of the monumental Second Symphony (Chicago/Barenboim

- this time as conductor). The scale is Brucknerian but the manner is

quite other; standing at the confluence of streams from Rachmaninov

(Piano Concerto No. 4), Grieg (Piano Concerto) and Busoni (Indian

Fantasy). The playing has a raw and unflinching tone with a darting,

heaven-scarring power specially evident in the finale (tr.3 3.16). The

recording also exudes an inwardness and spirituality distant from the

deep German forests conjured by the likes of Raff and Spohr. Notable

are the groans of disillusion at 6.40 in finale. This music is often

not a million miles from the bled exhaustion of the finale of Tchaikovskyís

Pathétique.

Then-Bergh was born in Hanover in 1916. His Berlin

debut took place in 1938. He engaged in a hectic round of concertising

after some Wehrmacht service. He was a professor at the Munich Conservatoire.

Having impressed the composer through his four concert performances

of Brahms' First Piano Concerto he was approached to perform the newly

revised version of the Concerto. After a lengthy period of joint study

composer and pianist tried the work through in private at the Salzburg

Mozarteum. Then-Bergh played it with the Berlin Phil at the composer's

memorial concert, Furtwänglerís death having frustrated a planned

joint performance.

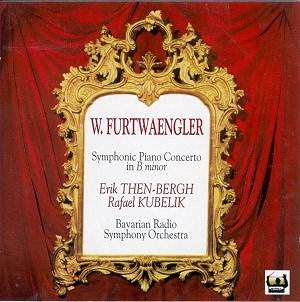

The Tahra production is made striking by the portrait

plates of Then-Bergh. The stereo recording sounds more than reasonable

if cluttered when at full blast.

This is a valuable document but perhaps at this very

moment Barenboim is planning a follow-up to his Chicago recording of

the Second Symphony. A recording of the Symphonic-Concerto would make

a splendid project for Olli Mustonen, Roland Pontinen, Rolf Hind, Hamish

Milne or Geoffrey Douglas Madge. We can dream canít we? Until then this

is a very fine account of a noble and tempestuous work.

Rob Barnett