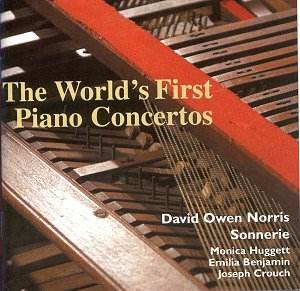

In the second half of the 18th century the new fortepiano

gradually pushed the harpsichord onto the sidelines. Alongside the

'grand piano' used on the concert platform, other kinds of 'piano'

were developed, which were mainly used in private rooms and salons.

Such an instrument is presented on this CD: the square piano, also

called 'table piano'. This instrument, which could be used both

as a side table and as a musical instrument, was especially popular

in England. One of the main builders of the instrument Johannes

Zumpe, was born in Germany but left his country for Britain in 1761.

The instrument used here for most of the items is a piano built

by him in 1769, exactly the year the Concerto in A by Philip Hayes

was composed, presented here as the 'first piano concerto' in the

history of music.

In Britain the square piano became very popular, and by the end

of the 18th century huge numbers of instruments were sold. But

during the 19th century the square piano lost ground to the upright

piano, the 'home version' of the concert grand. Until the end

of the 19th century square pianos were built, though.

David Owen Norris implicitly questions the generally held view

that square pianos were mostly used in private homes and by amateur

musicians, and were inferior to the grand pianos for 'serious'

music making. One of the characteristics of the square piano is

described by Mr Norris: "... the dampers were raised, not

by a sustaining pedal, but by two hand levers, one for the bass

and one for the treble. This meant that notes rang on until a

hand was free to 'change' the lever". This situation was

unchanged at the end of the century. It was different on the continent:

the famous piano builder Anton Walter also built square pianos;

they had a knee lever to operate the sustaining mechanism. And

in Vienna, composers and professional musicians took the square

piano very seriously.

David Owen Norris states that for more than two centuries, the

fact that square pianos in Britain had only hand levers "has

been perceived as a fatal disadvantage, ruling out Zumpe's Square

as a serious instrument: a puzzling verdict in view of its enormous

commercial success."

He also refers to the fact that a highly respected composer like

Johann Christian Bach acted as an agent for Zumpe and performed

on the instrument in public, which he wouldn't have done if he

had considered the square piano a kind of toy. Mr Norris closely

studied the music by Johann Christian Bach and believes some of

the characteristics of his keyboard music have been generated

by the peculiarities of the square piano. Some of the harmonies

only have an effect if the strings ring on. And he also believes

that "the need to avoid blurring forced him to avoid writing

too many notes". He concludes that Johann Christian turned

the peculiarities of the instrument to musical advantage.

The result as can be heard on this CD has convinced me. I have

heard the concertos by Johann Christian before, and was never

impressed; I often wondered where his reputation came from. For

some reasons, I found the keyboard concertos, in particular if

played on the fortepiano, bland and rather uninteresting. Having

heard the performance here I have changed my mind. All of a sudden

the concertos become quite dramatic. The other pieces on this

recording are equally interesting and musically satisfying. Mr

Norris has found in these concertos several characteristics that

seem to refer to the square piano as the instrument that the composers

had in mind. On this instrument they seem fully developed concertos

in their own right and not just predecessors of the 'real' classical

piano concerto.

All concertos are performed with two violins and cello. Any larger

ensemble would drown out the square piano. That a performance

with such a slight ensemble was common practice is proven by the

three concertos by Mozart, all arrangements of keyboard sonatas

by Johann Christian Bach. It is very likely that Mozart himself

played on a square piano by Zumpe, as an instrument signed by

Johann Christian Bach and built in 1778 has been found in France

near the village where Johann Christian and Mozart met in 1778.

It is an additional bonus that this very instrument is used here

in Mozart's Concerto in D.

But this recording isn't only interesting from a historical point

of view. The performance by David Owen Norris and Sonnerie is

excellent: lively and dramatic, with great expression in the slower

movements. The choice of tempi is very satisfying: most middle

movements are marked 'andante', and they are played as such, not

as 'adagios', as so often happens. Sometimes the tempo is held

back for a moment - for example in the andante of Mozart's Concerto

in D - which has a great dramatic effect.

I would strongly recommend this recording which brings together

a hardly-known instrument, fine music and excellent performances.

Johan van Veen

see also review

by Lewis Foreman

![]() for

details

for

details