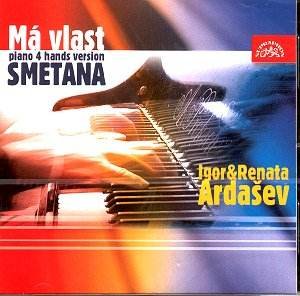

The Ardaševs play beautifully together — one

is reminded of other excellent husband and wife teams such as

‘Alexander and Dakin’ and Ingeborg and Reimer Küchler. In

addition, they make a striking looking couple, with Igor tall

and stoic with Renata having exquisite

large blue-grey eyes and long tawny hair. Igor studied with Paul

Badura-Skoda and Rudolf Serkin, then won fifth place at the Moscow

Tchaikovsky Competition as well as an amazingly long list of other

honours. Renata studied at the Janáček Academy of

Music and accumulated her own collection of medals before winning

the International Chopin Competition and the Gordon Trust Prize

in Glasgow.

Hearing this new version of this familiar and

beloved music is so exciting to me that I’ve been playing this

disk over and over all afternoon. The usual problem in performing

this work is that the musical and dramatic climax is reached with

#2, The Moldau, with a secondary climax with #4, From

Bohemia’s Meadows and Forests. After that, most orchestral

conductors let the intensity of the music fall off. The Ardaševs

do a great job of re-building intensity toward the end of #6,

Blaník, (Track 6) when Smetana brings the themes

of all the poems together in a rich counterpoint to provide a

grand coda. In orchestral recordings, only Vaclav Smetacek in

1981 was able to do so well.

Incredible it is to imagine that Smetana was

completely deaf before he began work on Ma Vlast and never

heard a single note of it.

These guys do a terrific job with all this, and

the impact of the performance is all the greater because it becomes

almost a chamber duet. The piano does not have the sweetness nor

the dynamic range of a full orchestra, of course, so the fugue

in #4 (Track 4) cannot be so hushed and mysterious as it is in

a good orchestral performance. Nor can the piano sing the Big

Tune of The Moldau (Track 2) so grandly as a big orchestral

string section. But what we gain is the intimacy of just two performers

who can play the work with a personal expression that makes an

orchestra sound like a clumsy, clunking machine. Phrases can be

shaped, inner voices clarified and rhythms accented beyond the

capability of any orchestra. For instance, many orchestral performances

get the timing wrong on the pizzicato violin accents in

the first ten bars of #2 whereas the Ardaševs get it exactly right,

of course. And they achieve more ominousness and spookiness in

the beginning of Tábor (Track 5) than I’ve ever

heard before.

Anyone who loves this music will want this recording

to sit beside their favourite orchestral version.

Paul Shoemaker