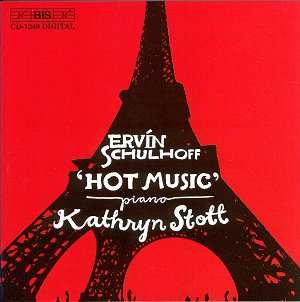

Czech composer Ervín Schulhoff is enjoying something

of a flowering. His music now turns up on concert programmes with

more regularity: see my reviews of Midori’s account of the Violin

Sonata (http://www.musicweb-international.com/SandH/2002/Aug02/midori.htm)

and Gottlieb Wallisch’s performance of the Piano Concerto (http://www.musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Nov01/youth.htm).

Czech record company Supraphon has also issued a fair number of

discs of Schulhoff’s music. He has been further highlighted as part

of the group of composers who were forced to attend concentration

camps. Most famous of these camps, possibly, is Theresienstadt,

although Schulhoff was to meet his end in Wülzburg.

Schulhoff numbered Reger as one of his teachers,

although his music encompassed a diversity of styles. The title

of the present disc, ‘Hot Music’, points towards the jazz influences

which preoccupied him. Schulhoff was introduced to jazz by the

Dadaist artist George Grotz. Of course, this was one factor that

troubled the Nazis (because of the African-American element).

Tellingly, Schulhoff wrote in 1919 that, ‘Music should first and

foremost produce physical pleasures’: much of the music on this

disc adheres to this, even becoming slinkily sensual at times.

The six movements of the Suite dansante de

jazz collectively provide the best, most approachable introduction

to Schulhoff imaginable. The bright ‘Stomp’ which opens the group

and the swing of ‘Strait’ contrast well with the ‘Waltz’, which

at 4’22 benefits from being the longest movement. Stott brings

care and delicacy as well as swing and panache to her reading.

Lasting almost the same amount of time as the

Suite, the First Piano Sonata (of five Schulhoff completed) is

made up of one span, subdivided into several sections. Stott provides

really considered, prepared playing: all the notes of the tricky

first section speak with a clarity that enables the piece to buzz

with energy. The Molto tranquillo, contrasting in mood, is a lovely

quasi-improvisation that is nevertheless not at all diffuse. Instead,

it is spellbinding in its progress towards its climax. Although

the finale brims with energy, it is the ‘Allegro moderato grotesco’

that is the highlight. True to the grotesque indication, it also

manages to be playful, with a lovely touch in its final gestures,

which lead directly into the last movement.

The Cinq Etudes de jazz is (compositionally)

quite held back, perhaps surprisingly given the title. The first

movement is recognisably a Charleston, but a virtuoso one. The

final ‘Toccata sur le shimmy ‘Kitten on the keys’’ is similarly

impressive, and these frame three affecting pieces, including

a remarkably delicate Tango.

The figure of J. S. Bach is invoked in the Toccatina

of the Second Suite of 1924 (where Stott’s fingerwork is

quite simply remarkable). Per Broman’s excellent booklet notes

refer to the influence of Ravel on this piece. Indeed Tombeau

de Couperin (1917) does seem to lurk around in the shadows.

Interestingly, the eleven Inventions are

notated minus barlines. This piece is dedicated to Ravel. The

booklet notes state that here Schulhoff’s music lies closer to

Debussy and indeed, and separately, my own listening notes referred

to Cathédrale engloutie in relation to the first

Invention of the set (marked, ‘Lento’). The final movement is

marked, ‘Allegro brutalemente’, as opposed to ‘martellato’, although

the effect is similar. Perhaps the most interesting is the capricious

ninth Invention, Presto leggiero, although at 26 seconds, blink

and you miss it.

The Hot Music elaborates and extends the

syncopations of the ragtime genre, taking it to various regions

(China in the case of No. 5!).

Musically, this disc is perfectly arranged to

provide an entertaining eighty minutes of listening. As an interpreter,

Stott is near-ideal (her previous recordings for Conifer had already

confirmed her status). Strongly, enthusiastically recommended.

Colin Clarke