The Quartets are

an under-investigated part of Martinů’s chamber output. Few

attempts stay long in the catalogue but the Panocha’s traversal

of all seven on Supraphon 11 0994-2 (three CDs) from 1980-83 LPs

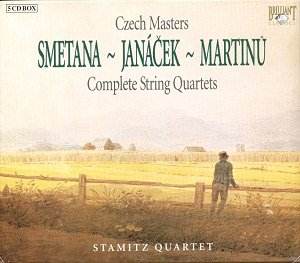

was consolidated into a box in the mid-nineties. The Stamitz,

originally on Bayer, now in this Brilliant Classics “Czech Box,”

also recorded the cycle, in 1990, an extensive period in the studios

for them as they also set down the Smetana Quartets included here

alongside the two Janáček from 1988. At Brilliant

Classics’ ludicrously cheap price one can investigate at will

the variety of Martinů’s inspirations and occasionally, it

must be admitted, lack or recycling of them.

The First Quartet dates from 1918 and is something

of a ’prentice work. The first of

the four movements is folk-influenced in the moderato passages

while strong Dvořák inflexions inform the melodic line. The

form is rather unconventional, the lyricism touched by a degree

of youthful sensuousness, and the key keeps shifting as if to

keep us on our toes. The slow movement

is impressionistic - he may not have reached it yet but Martinů’s

musical horizons were already formidably Parisian. The formal

transitions in this Debussyian movement are rather unexpected

and startling but moderately

effective, especially in this performance. Rhythmically the third

movement is propulsive with a trio section full of supple lightness

and the finale, the longest of the four movements, rather outstays

its welcome despite the return of the earthy Dvořák influence.

The Second Quartet followed seven years later in 1925 and it opens

with deceptive gentility – soon to be followed by brisk animation

and mildly Roussel influenced writing. The technique here is much

more concentrated and advanced even though he allows himself the

luxury of a combustible pizzicato episode. The work is at its

most impressive and most impressively played in the rather static

Andante, complex with occasional sforzati but bathed in dense

dark colours. It threatens fugato or Chorale development at one

point but manages pretty well to fuse a historically aware sensibility

with a modern occasional neo-classicist technique; the ending

is oddly bleak. Come the Finale though and textures are immediately

lightened and aerated – there’s a frisky solo violin cadenza,

rousing pizzicati and dancing, relieved drive. The Third Quartet

of 1929 concludes the first disc of this set. It’s the most compact

of the seven and consolidates but doesn’t much expand upon the

advances made in the Second; big thrummed pizzicati for the lower

strings, the viola’s line thick and deep and some motoric writing

all enliven the first movement. The second movement is a slithery

affair and the finale has real drive and splashes of bold colour

- painterly music.

The Fourth Quartet, the first of his so-called

Concerto da Camera Quartets (the other was the last), begins

in that bustly neo-classical School of ’37-’38 way so familiar

from his contemporary orchestral works. It winds down in another

technique familiar to admirers before developing renewed adrenalin.

Scampering drama informs the Allegro scherzando and I was taken

by cellist Vladimir Leixner’s inquisitive little contributions.

The Adagio is rather light in tone with a somewhat wandering tonality

but it soon settles into high-lying

violin writing and expressive middle voices. The finale is genial

and colourfully motoric once again – the dramatic “slow down”

of the material that Martinů so often cultivates is linked

to the similar incident in the opening movement and acts

as a contrastive device as well as imparting an intriguing sense

of stasis and reflection into the material. Following, a year

later, in the turbulent year of 1938, the Fifth is the greatest

of all the Quartets. The tough drive of the opening movement is

elastically extended to take in moments of lyrical, almost nostalgic

reflection. There is a sense of distinct tension as each of the

voices seeks out its individual line before the driving momentum

is once more resumed. The first violin part explores exceptionally

high-lying writing, expertly negotiated by Bohuslav Matousek,

himself a soloist of distinct ability. The Adagio utilises melody

from Kaprálová’s song Farewell Handkerchief

to poignant effect. The movement is unsettled, full of jabbing

violin and cello accents – the introspection is complex and emotional

convoluted, and this is surely not an extrapolation from what

we know, biographically, of his relationship with Kaprálová.

Insistent, repeated, bordering on the tensely obsessive, the Allegro

vivo continues the unsettledness of the work before the passionate

lament that opens the finale. This is the delayed heart of the

piece, its journeying-toward moment; the inward keening concentrates

in one focal point all the rhythmic and motivic shards that have

not coalesced, that have stubbornly

refused to cohere. Once done Martinů unleashes the full weight

of the Allegro conclusion – stern, bristling, allowing some more

innocent passages to emerge but turning back to the bridling,

arresting authority that the earlier emotional resolution

has now allowed. Not only is this a technically powerful work,

it is argued with strong internal dynamic and emotive contrasts.

It charts that movement with honesty and with genuine warmth and

power and stands as the summit of Martinů’s

control over the form, a focus of conflict and resolution he never

again attempted.

The Sixth Quartet was a post-war work, written

in 1946 in America. It’s essentially optimistic with folk-like

textures vaguely reminiscent of his earlier work in the quartet

form. It marks a distinct change from the pre-war Fifth, a work

suffused in personal and spiritual turmoil, and which embraces

in the Andante easy and free lyricism. The Andante here is quite

quick and has elegance and charm with only a few brief shadows

to intrude. The finale banishes care; spirited optimism prevails.

I suspect however that the Stamitz could have found just a few

more flecks of disappointment in the opening Allegro moderato.

The last Quartet, No. 7, dates from 1947, a period in which

he was still optimistic about his return to a professorship in

Prague. The Stamitz capture pretty well the sense of excitement,

almost friskiness – well, as near to frisky as Martinů gets

in a Quartet – that is engendered here. He even ends the opening

movement with a barely concealed little quasi-baroque procedure,

a joke-flourish of delightful panache and confidence. The Andante

is indeed one of his most sheerly beautiful and relaxed melodies

and one moreover that unfolds with unselfconscious, uninterrupted

eloquence. It is radiant, not at all accompanied by harmonic shifts

or neo-classical design, just plain unvarnished lyricism evolving

peacefully at its own pace. Eight glorious minutes. The joyous

and affectionate finale in a rather "old fashioned"

style hints indeed at Haydn and Beethoven along the way, almost

as if Martinů felt he had nothing left to prove or to demonstrate

in the form.

And indeed that was it. The rest of the disc

gives us the Madrigals of 1947 written for Lillian and Joseph

Fuchs. Matousek and Jan Peruska are lithe and elegant in the first,

exploit the fluttery whimsicality of the second with conviction

and skill – especially when they open out into reflective intimacy.

In the Allegro they are rhythmically solid and galvanizing – also

full of airy lyricism. The String Trio is the second he wrote

and dates from 1934. It’s in two compact movements, the first

doused with colourful neo-classicist intentions and incident,

harmonic and rhythmic, as well as a good sense of "space."

There are times when it does sound a little clotted – I’d like

to know how the Parisian dedicatees, the excellent sibling trio,

the Pasquier, managed it. A swift and comprehensive Poco moderato

ends the work – not a hugely impressive one but well worth hearing.

I’ll be brief with the remainder of the discs

not because the performances are poor but because most prospective

purchasers will be interested in this box for the Martinů.

The Stamitz essay both quartets by Smetana and Janáček. They

are fine, rather middle-of-the-road performances, honest and well

played. There are moments – in Smetana No. 1 and Janáček

Intimate Letters first movement - when a degree

of literalness can occasionally derail them. These are however

discreet, not over-emoted traversals; you won’t find much sleekness,

sensuality or emotive effusion – equally you won’t find leaden

phrasing or technical liabilities. Tonal blend is not as cohesive

here as it is with other quartets but the advantages are those

of individuality of phrasing.

A warm welcome to this disarmingly cheap set.

The Martinů Quartets are well

worth the effort to get to know and the notes by Milan Slavicky

point some of the way there – Karl Michael Komma writes on the

Janáček works. If you’ve not heard them, or have not heard

them all, I can heartily recommend this comprehensive

traversal of the unpredictable, occasionally highly impressive

works that make up the corpus of Martinů’s Quartets.

Jonathan Woolf

![]() for details

for details