Though it emerged as much by default as by design

Weingartner’s is still one of the most musically recommendable

of all cycles of the Beethoven Symphonies. His sagacity in matters

of balance, rhythm and tempo relation are as notable now as when

Weingartner set down these recordings. Quite unselfconscious in

matters of phrasing, with a determining impetus, few have sounded

less sentimental or more nobly grave. And when we arrive at the

Ninth one finds utterly undimmed his sense of clear-eyed mobility

allied to expressive depth. His control of the first movement

is absolute, imagination and clarity held in perfect accord, adopting

a tempo which whilst subject to a little flexibility is nevertheless

essentially one of logic and phrasal sensitivity. What one appreciates

more and more is his control of the long line, his avoidance of

show and gesture, of the superficial and passing. There is a refusal

to indulge metricality, his austere nobility of utterance is one

that would regard speed for its own sake not simply as a crude

imposition but, worse, as musical solipsism.

The Molto Vivace finds the Vienna fiddles on

fine, slashing form and the woodwind principals add their own

distinctive colours to the patina – the bassoonist and oboist

are especially characterful. The phrasing in the slow movement

conforms to everything we know of Weingartner’s supple gravity,

with the exceptionally fine violin line, the incision of the pizzicati

and horn playing adding even greater riches. The string cantilena

unfolds in a single unbroken span. The sepulchral basses makes

their unmistakable presence felt in the recitative of the last

movement in which Weingartner binds the syntax with a command

that never becomes slack. The finale is in fact notable for his

eagle-like vision in which one constantly feels oneself in the

presence of a control both lateral and vertical. The Chorus is

virile even if unpredictable – note writer Ian Julier rightly

cites the tenors’ occasional imperfections – but the quartet of

soloists includes the venerable bass Richard Mayr. The early Presto

section isn’t quite secure but by the Maestoso we are witnessing

a gripping intensity and the blazing cry of triumph in the Allegro

energico is really something. All this is possible because of

Weingartner’s heroic concentration

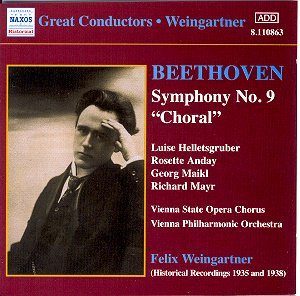

Coupled with the Ninth is The Consecration of

the House Overture, which receives a crisp and well-judged reading,

full of rhythmic drive and sectionally very well balanced. The

Columbia LXs had a good, wide frequency range that has been well

captured by Mark Obert-Thorn. It’s just and apposite that Naxos

has used a photograph of the young Weingartner, after the venerable

artwork of their previous issues in this series. For me his Beethoven

cycle will remain perennially sagacious, a compound of youth and

wisdom.

Jonathan Woolf