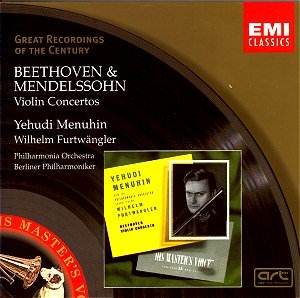

To compare this Beethoven with Menuhin’s first

stereo remake, recorded under Constantin Silvestri in Vienna seven

years later, is to obtain a lesson on the fickleness of inspiration

and human frailty. Silvestri conducts more than ably, and the

tempo is practically the same both times, yet Menuhin is edgy,

nervous, and often plays sharp. Despite a few flexible corners

as he settles down Furtwängler offers a remarkably classical

reading of the orchestral exposition – far more so than Bruno

Walter in his recording with Szigeti – but somehow he gives the

idea that each new idea is born in that moment. Thereafter he

and Menuhin are as one, a true dialogue as the ideas pass between

them. The slow movement under Silvestri seems episodic; Furtwängler

and Menuhin create a seamless flow. I have never before appreciated

so much the continuity of this movement. Menuhin begins the finale

at a fairly serene dance tempo; his phrasing is a little more

legato than we usually hear, and Furtwängler picks this up

so as to give a completely unified effect while Silvestri phrases

the normal way. At the first episode Furtwängler speeds up,

but he turns out to be right. Silvestri carries on at the same

tempo and it becomes a plod, so when Menuhin enters he speeds

things up on his own account. Menuhin and Furtwängler play

as one man, and this movement, too, is the best integrated I have

ever heard.

Not surprisingly, Menuhin returned to the concerto

only a few years after the Silvestri recording, this time with

Klemperer. Later still he remade it with Kurt Masur, but in the

opinion of many his truly great Beethoven concerto recordings

are the two under Furtwängler, of which this is the second.

There are those who feel that the 1947 version is more inspired

still, but since the present one is in very good 1953 mono sound

it can safely be recommended to the general listener in search

of a deep musical experience.

The Mendelssohn is rather more shrill as a recording,

but never mind, the performance is fiery and passionate in the

first movement, surprisingly mobile in the second and sufficiently

steady in the last to allow all the counterpoint to come through

clearly; genuinely vivacious, not merely fast. Few performances

make you so aware of the stature of the composer and of the work.

And yet … Furtwängler was an inspirational

artist who always gave his best before an audience. In 1952 he

gave this concerto in Turin – preserved in the archives – with

the volatile artist Gioconda De Vito. For every thousand people

who have heard the name of Menuhin, you’d be lucky to meet one

who knows that of De Vito, but she was a great violinist, too,

more romantic than Menuhin with a vocal style of phrasing that

looks back to Kreisler. She obviously got on well with Furtwängler

since the archives also contain a marvellous Brahms concerto from

them. There is a freedom and poetry, if at times a wildness, to

their performance which makes the Menuhin sound a shade studio-bound.

Some of Furtwängler’s RAI performances are coming out on

CD from the Istituto Discografico Italiano, so perhaps this is

on the way.

All the same, the Menuhin/Furtwängler collaboration

was an important one and all the discs they did together deserve

to be called "great". If you don’t know these two performances,

they’ll probably leave you marvelling anew at the music itself.

Christopher Howell