When J.S.Bach performed the St. Matthew Passion

on Good Friday in Leipzig, how many performers did he have? More

particularly how many singers did he have? Much academic ink has

been spilt over this issue. Bach routinely performed music at

St. Thomas's Church with tiny forces, and that on an ordinary

Sunday. One voice to a part was probably commonplace. He would

certainly not have been surprised at a performance like that on

the recent recording by Paul McCreesh and the Gabrieli Consort,

which uses just eight singers. But the Good Friday Passion was

a special event in the musical calendar and prefixed by a music-free

Lent, which would have given performers additional time to rehearse,

so some commentators argue that these performances encompassed

not just Bach's existing choir, but past pupils coming back to

join them. We shall probably never know, as there is frustratingly

little detail about the early performances of these seminal works.

Our performance tradition for Bach's Passions

dates from the 19th century when Mendelssohn revived

the work. Since then it has been shoe-horned into the standard

oratorio line-up which developed in the 19th century,

with four soloists (plus Evangelist and Jesus), large choir and

orchestra. The same forces could, effectively, perform everything

from Messiah and the St. Matthew Passion to Beethoven's Ninth

Symphony, Elijah and the Verdi Requiem. The last twenty years

have seen this monolithic oratorio edifice being dismantled as

we come to understand the differences in performance practice

in the works … even Elijah is starting to gain its eight soloists.

The St. Matthew Passion is designed to be performed

by double forces, eight soloists, double choir and double orchestra.

For his final version of the work, Bach even split the continuo

into two, so that there were consistently two different performance

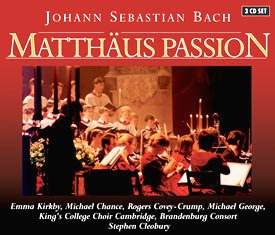

groups. This recording of the St. Matthew Passion is a very traditional

one. It uses a nineteenth century line-up with just four soloists

plus Evangelist and Jesus and though the choir is accompanied

by the Brandenburg Consort, playing on original instruments, the

recording has a very well upholstered sound. If Bach was prone

to fits of fantasy as he lay in bed at night after a taxing day

rehearsing and performing the work with inadequate forces, then

he may well have imagined this sort of well-upholstered performance

based, perhaps, on forces at court. It could be argued that this

type of performance is the fulfilment of this sort of supposition.

But we don't know, and it could just as well be that Bach would

have been horrified at the 'overblown' nature of the performance

compared to his lean Leipzig forces, but I doubt it. All we can

do is take the performance and judge it on its own merits.

The disc's primary advantage is the presence

of the choir of King's College, Cambridge. I love the sound that

this type of choir makes in this music, whether it is authentic

or not. (Bach's choir used teenage boy altos rather than counter-tenors).

They do sound glorious, from their opening moments in the very

first, great chorus. But as I listened to the performance more,

doubts began to creep in. It may be a fault of the recording process,

but I felt that the boys lack presence and I began to wish that

I were listening to a choir with a more continental sound. And

then there is the issue of diction. Performing and recording regularly

in an acoustic like King's cannot help, but the choir's German

diction leaves something to be desired. The soloists, particularly

Rogers Covey-Crump's wonderful high tenor Evangelist, have exemplary

diction which rather puts the choir in the shade. But when all

is said and done, King's still has that magical King's sound and

it is here in the service of one of Bach's greatest works.

John Eliot Gardiner has recorded the work for

Archiv with his mixed voice Monteverdi Choir and the English Baroque

Soloists with an array of fine soloists. Despite the differences

in type of choir it is a comparable recording to this one. Both

conductors even manage to come up with performances of a similar

duration, though their attitude to the different movements varies

and Gardiner is probably rather more interventionist. Also Gardiner

has far more separation between his two choirs, which makes the

double choruses far more effective.

On this recording, Michael George portrays Jesus

with a rather grainy voice and a significant amount of vibrato

which seemed entirely out of keeping with the performance. I found

his inability to deliver a true legato frankly disappointing,

but maybe he is simply on the wrong recording. Whereas Andreas

Schmidt, with Gardiner, is far more impressive and delivers the

role with a fine legato.

Emma Kirkby sings the soprano solos limpidly

and purely. Technically brilliant, I did think that she was sometimes

a little on the cool side but this is preferable to an over-blown

19th century manner. John Eliot Gardiner shares the

soprano solos between Ann Monoyios and Barbara Bonney and both

of them perform with style. Monoyios's "Blute nur, du liebe Herz"

is tenderly fragile but delivered with rather more vibrato than

Kirkby, and she fails to match Kirkby's bell-like clarity. In

"Aus Liebe will mein Heiland sterben", though Monoyios is beautiful,

she lacks Kirkby's clarity and no-one can match Kirkby's spine-tingling

first entry in this aria.

Michael Chance sings the alto solos with delicacy,

but his tone becomes a bit steely in the upper register, hinting

that the tessitura may not be ideal for him. John Eliot Gardiner

shares the alto solos between Anne Sofie von Otter and Michael

Chance, giving Chance "Erbarme dich". Comparing Chance's two performances

of this aria, Gardiner's speed is slower and somehow Chance seems

at his best for Gardiner, delivering the aria with a limpid purity

that is hard to match. For the remaining alto arias, von Otter

often sings them with a rather darker tone than Chance and she

does sound more comfortable with the tessitura, giving thoughtful,

shapely and moving performances. She has a fine sense of line

(something that Chance does not always achieve). But in "Können

Tränen meiner Wangen" it is Chance who, with a sense of shape

and style, gives the more affecting performance.

In the moving duet, "So ist mein Jesu nun gefangen",

Gardiner is much slower than Cleobury and the Monteverdi choir's

interruptions are far less violent those of King's. This slower

speed makes for a more moving performance, but Barbara Bonney

and Michael Chance find it difficult to sustain. Whereas, at Cleobury's

faster speed, Kirkby and Chance deliver an affectingly shaped

performance.

Tenor Martyn Hill is frankly disappointing. Singing

with a large bright voice and not a little vibrato, his passage

work is rather effortful and he seemed out of place on this recording.

For Gardiner, Howard Crook delivers the tenor arias matchlessly,

with an admirable feeling for line.

Bass David Thomas is a fine stylist but he does

not seem to be on the best of form on this recording. He makes

an impressively commanding bass soloist. But is a little too inclined

to bluster and smudge his passage work in the faster numbers.

Whereas for John Eliot Gardiner, Olaf Bär sings his solos

with a better feeling for legato and his soft-grained voice suits

the music perfectly. Bär shares the solos with Cornelius

Hauptman who sings rather emphatically in a manner not dissimilar

to David Thomas's

The smaller solos are taken by various unnamed

soloists, presumably from the King's Choir. Never less than adequate,

they do sometimes fail to completely convince.

Cleobury and Gardiner seem to show a differing

attitude to the chorales. Under Cleobury, King's sing the chorales

in a vigorous, four-square manner as if the congregation were

joining in (or we were going to join in at home) Whereas Gardiner

takes a more musical approach, treating the chorales as choral

contributions to be shaped. Both attitudes are valid and, like

much on these recordings, which you prefer depends on your personal

preferences.

The Brandenburg Consort play with élan

and give the music just the right lift when necessary. They contribute

a fine array of soloists in the obbligato parts for the arias.

There are the occasional smudged patches in the texture that suggest

that there was not quite as much studio time as would be desirable.

This is a fine recording though ultimately I

do not think that it measures up to the achievement of Gardiner

and his forces. For many people, though, the King's forces and

Emma Kirkby, with Michael Chance doing all the alto solos, will

prove a willing combination. And at super budget price, you cannot

go far wrong. There is a complete libretto in German.

Robert Hugill