Veronica Jochum – daughter of Eugen as I suppose she

must, even now, be introduced – studied with Rudolf Serkin though she’d

also taken lessons from Joseph Benvenuti in Paris. As she freely admits

in the accompanying booklet interview her admiration for her father

was so strong that Serkin, despite his own admiration for him, decided

on a complete break for her – and so she studied with Serkin in America.

From about 1960 onwards she has performed widely, with a repertoire

that takes in over thirty-five concertos. She is now on the faculty

of the New England Conservatoire of Music in Boston and has a strong

commitment to twentieth century music. Tahra has already issued a double

set of her performances, which included the first Beethoven Concerto,

two concertos by Mozart and Bartók 3 – all conducted by Eugen

Jochum. Also included was a world premiere performance of Edwin Fischer’s

Five Sketches (her plans to study with Fischer had earlier been thwarted

by his increasing infirmity).

There are two concertos here, the early B flat concerto

by Mozart and the Schumann (she is an avowed exponent of the concerto

as she is of Clara Schumann’s piano music which she has recorded). She

is accompanied by that fine musician Martin Turnovsky, Prague born and

a Szell student. She was fortunate in her conductor because Turnovsky

is an alert and stylish Mozartian and always has been. He conducts the

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in a 1969 radio performance with idiomatic

intelligence and together with Jochum they bring a youthful and pleasurable

sensitivity to the work. Her cadenza in the opening Allegro aperto is

properly scaled and she is affectionate in the slow movement. Tight

and bright rhythm informs the finale, with a good spring in Jochum’s

left hand, and Turnovsky is careful not to allow the horns to engage

in too stentorian and florid a flourish. In fact he is perspicaciousness

itself here – nothing overblown, everything properly accorded its rightful,

balanced place.

The Schumann Concerto marked the last time the two

Jochums played the piece together – though it was by no means the end

of their concert giving together. Oddly enough, though this was recorded

in the Salle Pleyel in 1982, the sound is significantly less immediate

than in the case of the Mozart recorded thirteen years earlier in Bavaria.

There is also some orchestral congestion. This is a well-shaped and

seemly performance though not one that offers any true insights into

the work. There is a sense of caution in the Allegro affettuoso and

whilst the Intermezzo is negotiated with skill and sensitivity, the

Allegro vivace finale – whilst properly accommodating of the poetry

and drama of the movement and negotiated with digital finesse - seems

to hang fire. The basses are, it’s true, nicely dark, and there is nothing

speciously Olympian or melodramatic either but there can be a want of

fire and excitement.

An attractive coupling nevertheless - and one that

will remind people that there is more than one Jochum in the musical

firmament.

Jonathan Woolf

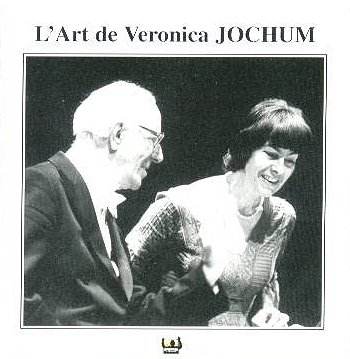

![]() Veronica Jochum (piano)

Veronica Jochum (piano)

![]() TAHRA 487 [50.43]

TAHRA 487 [50.43]