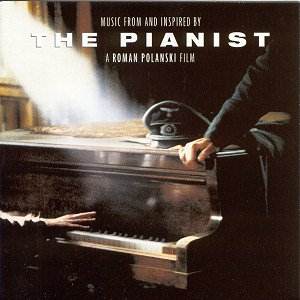

The music of the film Ė The Pianist, directed

by Roman Polanski. The subject is Wladislaw Szpilman, a pianist, who

takes refuge in a Warsaw Ghetto during World War II having avoided being

shipped to a death camp thanks to the aid of a music-loving SS officer.

As I understand it! I havenít seen the film, nor are there any notes

in the CDís booklet, which is though graced by several stills from the

film. I must presume that given the CD has at least 20 minutes more

playing time available that all the music featured in the film is included.

Of the nine pieces by Chopin, Janusz Olejniczak plays eight. Of these,

three are newly recorded in 2001, four are from 1991 and the Prelude

is from 1994. On what might be considered a bonus track, Wladislaw Szpilman

himself recorded the Mazurka in 1948.

The three nocturnes open the CD. They flow and are

spontaneous; Janusz Olejniczak plays with mellow tone and concentrated

expression. However, as one listens further, his sound and expressive

palette becomes somewhat limited. While he commands a wide dynamic range

and an unforced fortissimo (try the climax of the C minor Nocturne),

I was neither wholly absorbed nor totally convinced once past the engaging

without-opus-number C sharp minor nocturne. In short his is good if

limited playing.

I am left to suggest that this CD is a souvenir for

those who see the film and like the music. In this respect it is a perfectly

fine release, and people buying it thus wonít be disappointed or worry

about the mingling of different-year recordings that betray slightly

higher hiss levels in the earlier takes, the tape endings of which are

rather precipitated in their splicing. Nor will it be of paramount concern

that Olejniczak, while a sensitive player, one who has Chopinís music

in his fingers if not always his soul, proves too volatile an interpreter.

For example, the way he takes off a couple of minutes into the F major

Ballade is too contrasting; other such diversions mark Olejniczak as

a sectional Chopin interpreter Ė hereís one mood, now another, the whole

seems less important. He is also too percussive. I donít doubt the passion,

although Iím not sure this music communicates as it intrinsically might

when bravura and demonstration are as nakedly detailed as here.

Thereís a similar head-banging start to the G minor

Ballade, the most popular of the four, before a welcome yielding to

introspection. Even so, there is a note for note realisation that while

far from being literal also leaves the door open for something altogether

more illuminating and identified; itís an entrance Olejniczak doesnít

go into. Overall, his agenda is more assault and battery than poise

and growth. Fans of Kissin might like it! The waltz could be more seductive,

the prelude more suggestive of latent melancholy, and the Andante spianato

is too lumpy and perfunctory for the calm lake that this music should

be. The orchestra enter for the Polonaise, its textures inflated by

too cavernous an acoustic (the same one that is unhelpful to José

Curaís new recording of Rachmaninovís Second Symphony).

Track 10 is Kilarís two-minute piece, written for the

film presumably, that is a slinky and doleful example of Klezmer-tinged

music, here for clarinet and strings, its diminuendo close produced

it seems by the control room rather than the players.

Finally to the single example of Szpilmanís own playing.

The sound is somewhat primitive but no barrier to enjoying playing that

has an emotional interior that finds the soul and shape of this archetype

of Chopinís most elusive oeuvre. A CD, then, for the souvenir-hunter.

With the exception of Szpilmanís four-minute appearance, I donít think

serious collectors need be troubled.

Colin Anderson

![]() Janusz Olejniczak

(piano)

Janusz Olejniczak

(piano) ![]() SONY SK 87739 [58í30"]

SONY SK 87739 [58í30"]