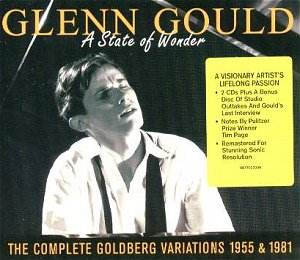

There are, or were until recently, five Gould versions

of the Goldberg Variations in the catalogue of which three date from

around the mid to late 1950s, the time of his first classic commercial

traversal (I have a strong affection for the Salzburg recital of the

late 1950s with its Sweelinck Fantasia companion). Sony Classical’s

three CD set consolidates the 1955 and 1981 recordings adding for good

measure – and it’s very good measure – out-takes from the earlier recording

session and a radio interview between Gould and Tim Page, made shortly

before the pianist’s death. The remastering of the 1981 sessions is

from the original analogue source tapes, not the original digital masters,

the technical ramifications of which are detailed in a note in the elegantly

produced open-out book format.

What Tim Page calls the alpha and omega of Goldberg

recordings demonstrate the profound distance Gould travelled between

his young manhood – he was twenty-two when he made the 1955 recording

– and the prematurely aged "eccentric" of forty-nine whose

last aural testament this was. That Gould disdained much of the earlier

recording should not come as a surprise and his intensely honest and

thought-provoking refutation of his earlier "pianistic" self

– singling out a variation for his having played it like a Chopin Nocturne

– is a source in itself of reflection and analysis of appropriate touch,

tone and approach. His older self’s increasingly puritan self was retrospectively

horrified by such an unseemly and overt demonstration of romanticised

sensibility. In 1955, lasting 38 minutes Gould includes no repeats.

In 1981, at thirteen minutes longer, partly as a result of extended

tempi but also because of repeats, he plays first half repeats in variations

3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 12, 15, 18, 21, 21, 24, 25, 27 and 30. In the earlier

recording, and in Salzburg for that matter, Gould’s Goldberg Variations

are full of grace and animation; there are times, it’s true, when measured

against his later performance the youthful one can seem precipitate

and too energised for clarity of articulation, though this is a relative

matter. But there is magnificent drama and sometimes a sense of euphoric

abandon hard to resist, a sense in the final variations of the arch

of the music taken in a single span, a sense of flux engendered through

passionate continuity. By contrast, by 1981, though there are still

numerous points of engagement and despite Gould’s still deepening unveiling

of architecture and touch, there is something of a loss of spontaneity.

That said, despite the occasional finicky articulation, the 1981 performance

seems too often to be judged on the admitted extreme slowness of the

Aria. Once this can be reconciled with the performance as a whole –

if it can – Gould’s last performance of the Variations has a clarity

and perception that demand the highest concentration. In this performance

he frequently clarifies details that in the 1950s were perhaps too youthfully

propulsive. It’s still mandatory listening.

The third disc also includes Gould spoofing British

actors in his interview with an obviously ill at ease Page – hardly

a moment that will live in the annals of comic history (Gould could

be surprisingly laboured in his humour). He expounds on his love of

contrapuntalism and deliberate tempi and his cultivation of a single

pulse in music. The out-takes contain break-downs, problems with the

piano in the New York studio, and a Gouldian trick speciality, his conflation

of God Save the King and The Star Spangled Banner.

Repackaged in this format makes this an attractive

prospect for those who have only one or other of Gould’s Goldbergs.

For those who have neither, these discs will grant (sometimes baffling)

greatness in Bach interpretation.

Jonathan Woolf

See also A

Quintet of Goldbergs by Christopher Howell