It’s interesting to speculate – interesting if fruitless

– on the fortunes for Rebecca Clarke’s Viola Sonata had it been recorded

in the 1920s or 1930s. Columbia embarked on a mini series of composer-authorised

sonata recordings – Albert Sammons and John Ireland in the latter’s

Second Violin Sonata, Lionel Tertis and Arnold Bax in his Viola Sonata,

both of which fell prey to the unfavourable economic climate of the

Wall Street crash and were never issued (though they both survived and

are now in the catalogue, the former on Dutton, the latter on Pearl).

Clarke was a viola player herself and a fine one, and received some

lessons from Tertis (though he doesn’t mention her in his autobiography)

but she made only one recording, for Compton Mackenzie’s National Gramophonic

Society in 1930 – Mozart’s Kegelstadt Trio with clarinettist

Frederick Thurston and pianist Kathleen Long. If Aeolian Vocalion had

been more on the ball they might have given the work an airing between

1920 and 1924 – they had Tertis on their roster of artists at the time

or could have signed the young composer herself. It would certainly

have raised her profile if nothing else. Still, a fruitless diversion

given the relative indifference with which her work was received by

recording companies and promoters at the time.

Her time has come of course, and it’s true not just

of the Viola Sonata which has a number of recordings to its name – Garfield

Jackson and Martin Roscoe on ASV, Dann and Vogt on CBC, Schotten and

Collier on Crystal, Coletti and Howard on Hyperion (for some a front

runner - review)

as well as Riebl and Höfer on Project Arts Nova and more recently

Helen Callus and Robert McDonald, again on ASV – a most well-chosen

disc coupling Clarke (and including Morpheus and Lullaby as well) with

works by Freda Swain, Janetta Gould and Pamela Harrison.

[see also Clarke, Martinu and Regaer Viola Sonatas on Calliope

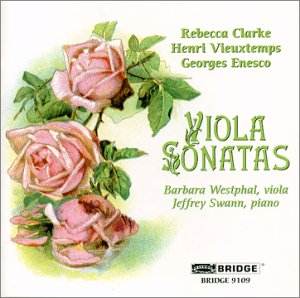

- LM] Barbara Westphal and Jeffrey Swann’s disc was recorded

and released in 2001 and makes a versatile addition to the catalogue,

coupled as it is with Enescu’s youthful Concert work and Vieuxtemps’

established mid nineteenth century classic. Westphal is excellent in

the folk inflected episodes of the Impetuoso first movement of the Clarke,

bringing off the quasi-improvisatory opening flourish with creditable

panache. She can mine the consolingly reflective second subject as well

– even if the repeated notes here did not sound absolutely vibrant –

and catches the lift as the movement opens out expressively, Jeffrey

Swan offering finely graded dynamics. Westphal and Swann are not as

vigorous in the Vivace second movement as some but they do explore the

implications of the vertiginous decent from highest to lowest strings

fully – and bring a playful patina to the movement. Swann’s rippling

piano work is pleasurable here and Westphal follows the viola’s lyrical,

somewhat discursive line with intelligence and judgement. Westphal maintains

intonation in the highest registers in the difficult finale and she

brings a cultivated simplicity in terms of tone and line. In one of

the work’s most tricky passages – the transitional moment from Adagio

section to Allegro – embodied by the buzzing viola, she emerges well.

As the work draws to an end Westphal and Swann successfully explore

the contrastive interior and exterior material.

Vieuxtemps’ Sonata dates from 1863 and is in three

movements. Westphal and Swann are certainly attuned to its brand of

stately nobility in the opening movement and manage to contrast this

with moments of little declamatory outbursts. The conclusion is effected

with maestoso grandeur, Westphal full of depth and sensitivity. The

second movement is a whimsical little Barcarolle, variational, exploring

registral potential in the viola – both light and dark – and the finale

a bounding, charmingly off-hand creation. In fact the work lightens

as it develops, divesting itself of pomp and embracing charm and lightness.

To conclude we have Enescu’s prentice work – rather pastoral and full

of roulades and double stops, covering some stylistic ground – including

the salon – as well as testing register solidity and vibrance in the

performer. In the faster section of this nine-minute work there’s a

degree of room for expressive elasticity. Enescu apparently said that

he wrote the work as a student and arranged it for viola and orchestra

(a version now lost). It does certainly resemble, as the notes suggest,

a conservatoire test piece in its all-embracing potential for lyrical

and digital freedom.

This is a useful recital that dispenses with the chronological

running order – it starts with the Clarke – and is attractively phrased

and well played. Notes are good and sound quality excellent.

Jonathan Woolf

![]() for

details

for

details