Joyce Hatto was a piano pupil of Zbigniew Drzewiecki

at the Warsaw Conservatoire as was Roger Woodward amongst others. Drzewiecki

(1890-1971) was a strong proponent of the contemporary Polish repertoire

but equally committed to Chopin, on whom he was an authority. She also

studied with Ilona Kabos and Serge Krish, received some guidance from

Cortot and took composition lessons from Mátyás Seiber

and from Hindemith. Record collectors will remember her remarkable Bax,

but there was much else – Mozart, Rachmaninov, Gershwin – and she was

a sterling exponent of Liszt as well, having given the complete original

piano works in a series of recitals, a remarkable and indefatigable

undertaking.

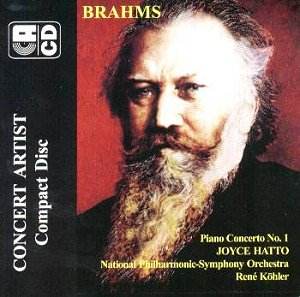

Concert Artist/Fidelio have captured a sizeable chunk

of her repertoire in recent recordings of which this Brahms release

forms part, recorded in 1995 and 1997. New releases are imminent so

I suggest you consult the company’s website (details above) for further

details. Hatto has recorded both Concertos – my review of the Second

Concerto will appear soon – and she displays considerable Brahmsian

qualities; this is a pianist who should be far better known than she

is. I don’t know anything about the National Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra

(or conductor René Köhler) but the name has a charming Decca

resonance familiar from the days of Sidney Beer, Warwick Braithwaite

and Anatole Fistoulari. The orchestra, it’s true, is recorded in a rather

swimmy acoustic and this saps the lower strings especially with a lack

of clarity that can prove burdensome. But Joyce Hatto is on splendid

form, strong, resilient; she opens up space, little pockets of weighted

time, in the left hand. She never tries to force through the tone or

to engage in tonal mock-heroics. In the Maestoso first movement she

can retard the rhythm with remarkable effect, vesting her chording with

passionate dignity and the verticality of the chords is as noble as

their tone is rich. After noting the problem with the acoustic I should

add that the basses and cellos come into their own in the slow movement

in which at a relatively slow tempo Hatto sustains the questing line

with sensitivity and architectural acumen. The balance between piano

and orchestra is good in the finale and even if the timpani booms alarmingly

it seems to add to the increasingly pawky humour of the reading which

reaches its apotheosis in this performance in the fugal episode, very

well done. Altogether in fact a convincing performance of a frequently

misread work.

The disc ends with three Rhapsodies; the Op. 119 No.

4 is the last of Brahms’ compositions for piano and excellently played

by Joyce Hatto. The Op. 79 Rhapsodies are sensitive and characterful.

She reminds me a little of Kempff in the B minor with a compelling but

deliberately circumscribed tonal palette. In the G minor she begins

well, with choppy left hand and stabbing accents though maybe missing

some of the mystery in the chordal passages – nevertheless she’s keenly

alive and whilst I found a lack of differentiation between piano and

forte and lack of dynamic variance, that could be a recording phenomenon.

As I said it’s no superficial swagger such as even elite pianists all

too often make it (and I recently heard a pianist I much admire, Ivan

Moravec, murder it in concert).

A reading of some considerable distinction then from

a pianist now making a considerable presence once again in the catalogues,

due almost entirely to the dedication and support of a record label

that sticks by artists it believes in.

Jonathan Woolf

see also

JOYCE

HATTO -

A Pianist of Extraordinary Personality and Promise:

Comment and Interview by Burnett James

MusicWeb

can offer the complete Concert

Artist catalogue