The

first note on the CD, the first note of Zdravitsa, hooks

you; it’s utterly gorgeous. Both orchestra and chourus performances

throughout are top drawer, and the sound is fully up to Chandos’s

extremely high standards even though this recording was made in

Russia. Praise be that the text of Zdravitsa is sung in

Russian, for it is awful fawning pseudo-patriotic Stalin worship.

But rather than attack Prokofiev for writing music to such texts,

we should consider music written by Bach, Beethoven, et al., under

similar circumstances and reflect that some things do not change

much. And so long as the music is so beautiful, why worry if we

don’t like its politics? Reflect that Stalin is dead, the music

is alive, and Prokofiev’s genius lives forever.

Flourish

Might Land is similar in character, briefer and not quite

so high in quality, but still very much worth hearing.

Autumnal

is delightful, a short atmospheric tone poem he began at the conservatory

and worked on for 24 years. It might be compared to Stravinsky’s

Fireworks, also a brief, early, colourful teaching piece

that did not reflect the mature style of the composer; or to Anton

Webern’s affectionate farewell to Straussian romanticism, Im

Somerwind.

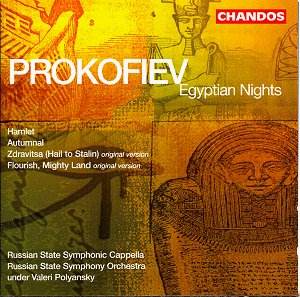

Egyptian

Nights is the title of an unfinished monologue by Pushkin;

by amalgamating some of Shaw and Shakespeare, Tairov put together

a play and Prokofiev provided incidental music for the production

in 1938. The seven numbers making up Op. 61 have exotic sounding

titles, but the music is not Prokofiev’s best, not comparing favourably

with the character pieces from Romeo and Juliet. ‘A Night

in Egypt’ is a steal from night music from Act III Scene 1 of

Verdi’s Aïda. The other brief pieces are more original

but sound much like background music. Perhaps the best are a four

minute musical portrait of Mark Antony and the five minute ‘Fall

of Cleopatra.’ The four minute ‘Roma Militaris’ consists of menacing

fanfares and could be taken for an excerpt from one of the later

symphonies. Other Russian composers have written music with this

title, as the Pushkin fragment continues to intrigue Russian dramatists.

The

Hamlet music consists of Ophelia’s songs and the gravedigger’s

songs, as well as five orchestral pieces. The question arose as

to whether Danish or English folk songs would be more appropriate,

and Prokofiev has chosen to use some ‘English’ folk songs (including

The Campbells are Coming!) to set these Russian translations.

From the four language parallel texts we learn that the Russian

for Hey nonny nonny hey nonny is Zi vertis, vertis,

vertis, vertis which can be roughly re-translated as ‘round

and round and round.’ The songs are pleasingly lyrical and well

sung, and the orchestral sections demonstrate Prokofiev’s amazing

ability to write deliberately unfocussed music that can be trusted

to remain in the background.

Paul

Shoemaker