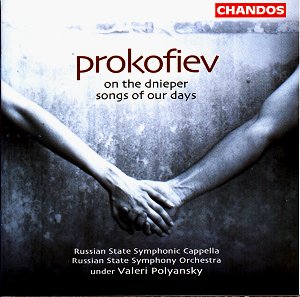

The

ballet On the Dnieper was one of the first works in Prokofiev’s

new simpler style. This style emerged after the failure of his

Second Symphony discouraged him from further experiments in musical

complexity. It also succeeded the death of Diaghilev and Prokofiev’s

bitter quarrel with George Balanchine; a falling out that so completely

changed the character of his working relationship with the Ballets

Russes. Parisian audiences didn’t like it. Prokofiev hadn’t yet

got down the difference between writing simply and writing vaporously.

Even as superbly performed as it is here, the music is pretty,

occasionally lovely, even charming, but in general is just forty

minutes of pleasant background. Nothing here could be mistaken

for the slow movement or scherzo of a symphony. The scenario is

passionless Socialist utopianism about rival lovers settling their

differences with reference to the greatest good for the greatest

number. One Parisian critic asked if it were to be taken as a

joke.

Songs

of Our Days is a setting of ‘...contemporary texts published

in Pravda...’ all at least obliquely in praise of Stalin and was

written just after Prokofiev had moved his family to Russia and

severed all ties to Paris. The text was alleged to consist of

Ukrainian and Belorussian folk poetry, and was well received in

Russia; following the performance Prokofiev was given permission

to travel with his wife to the USA — for the last time. Of course,

his sons remained in Russia, so it is not surprising that Prokofiev

refused generous financial offers to remain in the US and returned

home on schedule.

Fortunately

the texts are sung in Russian and are hence incomprehensible to

Anglophones,* although they frequently express authentic folksy

sentiments and are performed here with broad feeling and sense

of fun. Musically this is the Prokofiev of Peter and the Wolf

and Cinderella and the music is engaging and colourful.

The overall effect is that of a rousing folk opera, and is a nice

antidote to the somnolent mood established by the ballet. Baritone

Igor Tarasov deserves a special medal for his clear rapid-fire

delivery; if G&S is done in Russia, he would be the choice

for the patter songs. Mezzo Smolnikova sings the Lullaby

with great lyrical affect. ‘Bayushki-bayu’ (‘sleep little

one, sleep’) is left untranslated in the printed English text.

*unless

you want Russian texts to help you study the language; they are

very good for this use as they are clearly enunciated and conversationally

phrased. The Russian texts are printed in Cyrillic.

Paul

Shoemaker