This

disc is part of an exciting series on the superb NMC label that

aims to give us back catalogue and deleted issues at mid-price.

This in itself is to be applauded, but as the man behind NMC,

David Matthews’ brother and fellow composer Colin Matthews, states

in the booklet ‘NMC’s principle, from the beginning, has been

never to delete…so it’s a natural development for NMC to acquire

and re-release significant recordings that have disappeared from

view … and breathe life into music that should always be at hand’.

It is shameful that the big record companies do not have more

faith in their own catalogue, and contemporary music suffers most

from the deletion axe.

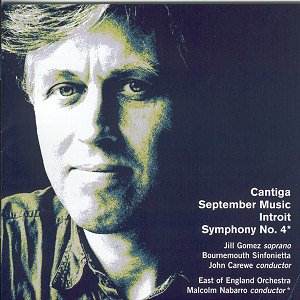

These

performances actually originated on the excellent Unicorn and

Collins labels, both of which suffered the ultimate fate, so we

really must be grateful that such superb music as here is rescued

and is now available to a whole new public. The most substantial

item is the 4th Symphony, originally a CD single

(itself a good idea), and a very imaginative and compelling piece

it is. It is classical in proportion and design (though in 5 movements)

and the scoring is even for a Haydn-like ensemble (it comes as

no surprise that it was commissioned by the English Chamber Orchestra).

Any

‘modernist’ features are consciously kept in check, and one is

aware of great harmonic, textural and, particularly, melodic content

being uppermost in the composer’s mind. There is great physical

energy here and not a little Haydnesque humour. The second movement

is an intense, rhythmic scherzo and is followed by a song-like

andante scored mainly for strings. I love the witty fourth movement,

marked fast tango, slightly manic, and it makes a quirkily

inventive replacement for the classical minuet. The whole piece

has the feeling of a real symphony, where ideas are often linked

and logically lead on to satisfying conclusions. The performance

is good rather than great, the strings being a bit stretched in

places (what a pity it’s not the ECO), but in no way does it seriously

mar enjoyment.

The

other really substantial work is Cantiga (simply the Spanish

word for song), which is subtitled The Song of Inês de

Castro, and is a dramatic scena based on a poetic narrative

by Maggie Hemingway. This famous historical ‘legend’ has proved

fertile for composers (James MacMillan chose the bloody, doomed

romance for his first opera) and Matthews has fashioned an Expressionistic

mini-opera that is powerful and brooding. The modest orchestral

forces are used with great ingenuity, particularly the two interludes,

and the whole thing lingers in the memory, so strong is the atmosphere

conjured up. The success is due in no small way to the performance

by Jill Gomez, who suggested and then commissioned the work, and

her deeply felt and superbly committed singing is unlikely to

be surpassed.

The

two smaller pieces add effective balance to the disc. September

Music is lyrical, heartfelt and almost Impressionistic in

its colours, and the string writing strikes me as continuing a

long line of great English string works. The ‘English’ connection

is also apparent in Introit, with its echoes of Tippett

(particularly the main 5-note idea) and Vaughan Williams. Indeed,

Matthews admits quite openly to paying homage to a number of English

composers in the piece which, far from sounding derivative, actually

heightens the moving sense of tradition and context. When the

two trumpets finally enter near the end, the glorious bell-like

peroration evokes a musical heritage that feels as solid as the

Cathedral setting it was designed for.

Recording

quality is first rate throughout, and performances are in the

main excellent. The presentation is ideal, with authoritative

and readable notes by the composer, together with song text and

biographies. A superb issue which deserves success.

Tony

Haywood